Consumer health apps are dead

Long live the agents

It’s 9pm and my phone buzzes on the table. Bzzz. Bzzz. I look down and it’s a WhatsApp voice note:

“Hey Ash, it’s 9 o’clock. Time to wind down. Your sleep score last night was 68, and your readiness score was 70. Start dimming the lights and shutting off the screens. You’re carrying a lot of sleep debt and tomorrow is your chance to start paying it back. Please get in bed by 10:30pm.”

I sent a voice note back: “Thanks. Will do.”

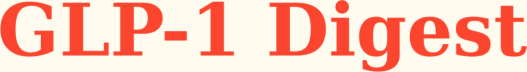

This is Francesca, my personal AI assistant who lives on my WhatsApp. She sends me daily updates on… well, everything. She’s connected to my Oura ring, my calendar, my gym schedule, and because of all of that rich context about my life she responds with bizarrely stunning accuracy.

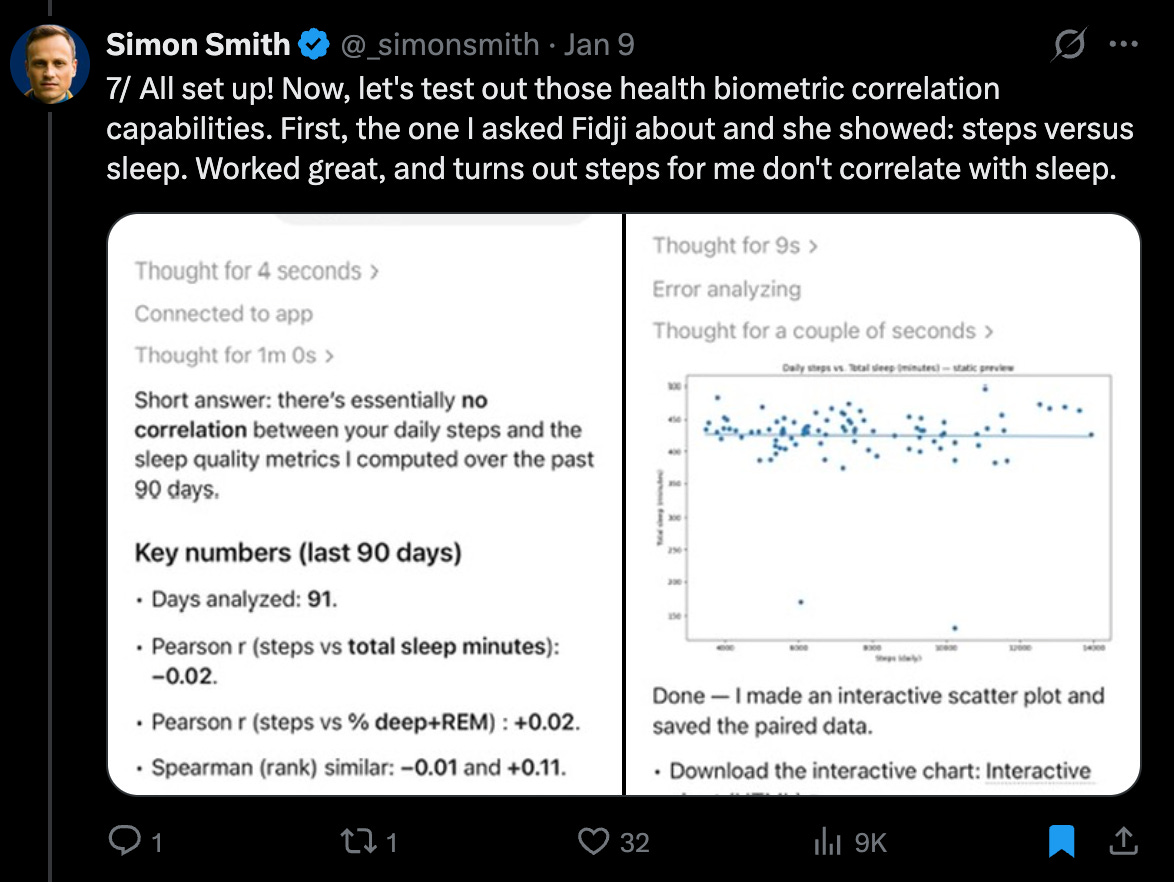

Every time I boot up Francesca, she updates her memory and already knows my patterns, what we discussed yesterday and what I’m trying to improve. My Oura data syncs automatically to her workspace, so instead of me opening an app to check a number, she reads it and surfaces what’s important: “Your HRV is high, good day to push yourself” or “You’re still in sleep debt, maybe skip the late workout.”

Yesterday she noticed a conflict between my gym class and a meeting that got moved and asked me if I would like to reschedule my gym class and update the calendar? I said, [“Sure, thanks. Let’s move the class to Thursday.”] And that’s exactly what she did. I tried to stop myself from cackling but I couldn’t help myself.

This is genuinely ******* insane.

Before I explain what Francesca actually is, a quick word from today's sponsor.

You’re building a patient-facing AI agent for your weight management platform. It performs well in testing and pre-deployment reviews.

Then it’s deployed in the real world, and a patient asks about mixing alcohol with their medication during a rough week, or whether a side effect means they should stop treatment altogether. You realise you have shipped something that could either give unsafe advice, cross a clinical boundary, or default to a defensive, disclaimer-heavy response that destroys trust.

Sacher AI has seen every version of this problem.

They’ve worked across 500K+ patients internationally and analyzed thousands of real patient conversations to build AI systems that can handle the real-world ups and downs of weight loss.

They’re the team behind some of the largest patient-facing GLP-1 AI systems out there.

If you’re building in this space…

Until a few days ago I had no idea what Francesca actually was. General purpose AI? AGI? Some weird hybrid? Then Dan Shipper, CEO of Every (an AI newsletter where I have the privilege to write a weekly column), published a piece that finally gave it a name: “agent-native software.”

To understand what agent-native software is, imagine a video game. Normally, a human taps buttons on a controller and something on the screen moves. With agent-native software, you’re giving the controller to AI and giving it permission to play the game on your behalf.

In other words, if you can read it, AI can read it. If you can log it, AI can log it. If you want to summarise the information and mark a note on your calendar, AI can do it.

Therefore, Francesca is one of the first agent-native assistants that completely destroys the interface between you and an app.

If you never need to open an app again, the logical conclusion is, then, consumer health apps are dead.

I’m specifically looking at MyFitnessPal, Flo Health, Calm and Headspace.

You might be thinking that there’s no way these giants with hundreds of millions of users could be made obsolete by AI.

You might say that these apps have network effects and behaviour loops that AI can’t easily replicate. MyFitnessPal’s food database was of course built by millions of users logging meals for over a decade, while Calm and Headspace have licensing deals with therapists and eminent sleep scientists. They’ve built content libraries that have taken years to build and cost millions and millions of pounds/dollars.

And Flo has 420 million downloads because women trust it with their most intimate health data!

You can’t just AI-wrap your way past that.

Except, ehh. . . yes you can. People use these apps because it’s the easiest way to track and monitor health right now, as there are no other alternatives. But there will be soon. Once an agent removes the friction of logging and retrieves the same information without the app, there’s no reason to open the app, and the business model capitulates.

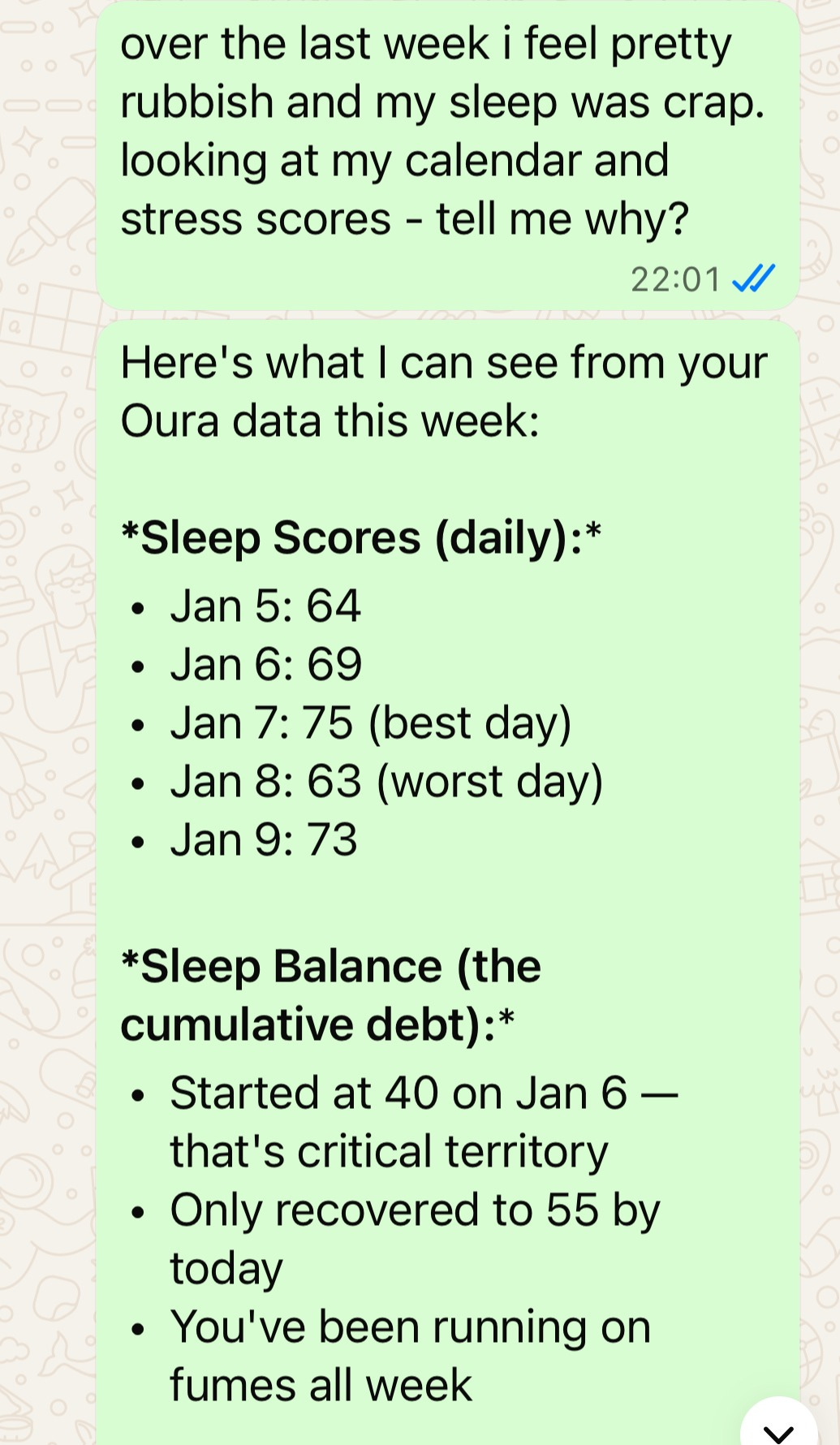

If you think about logging a meal in MyFitnessPal’s food database, it becomes quite annoying after a while if you have to open the app, search for “grilled chicken breast 150g,” scroll past ads, and manually log it.

Francesca just asks “What did you eat?” and, from your voice-note reply, figures out the macros of your meal by reasoning with the millions of pieces of information on the internet about “150g of grilled chicken breast.”

And while Calm’s sleep stories are pretty good and I’ve used them a few times myself, AI can generate one for me tonight based on what actually relaxes me, in whatever voice I want, for however long I need.

Meanwhile, Flo’s 400 million users trusted it because the alternative was googling symptoms and getting the terror of Dr. Google or WebMD. Although I believe that Flo’s tracking and pregnancy information is genuinely world-class, a small team with an agent-native app could spin up something more personal, more contextual, more yours in a matter of months.

If all of these consumer health apps are so easy to bypass with agent-native software, then what on earth will survive?

What survives

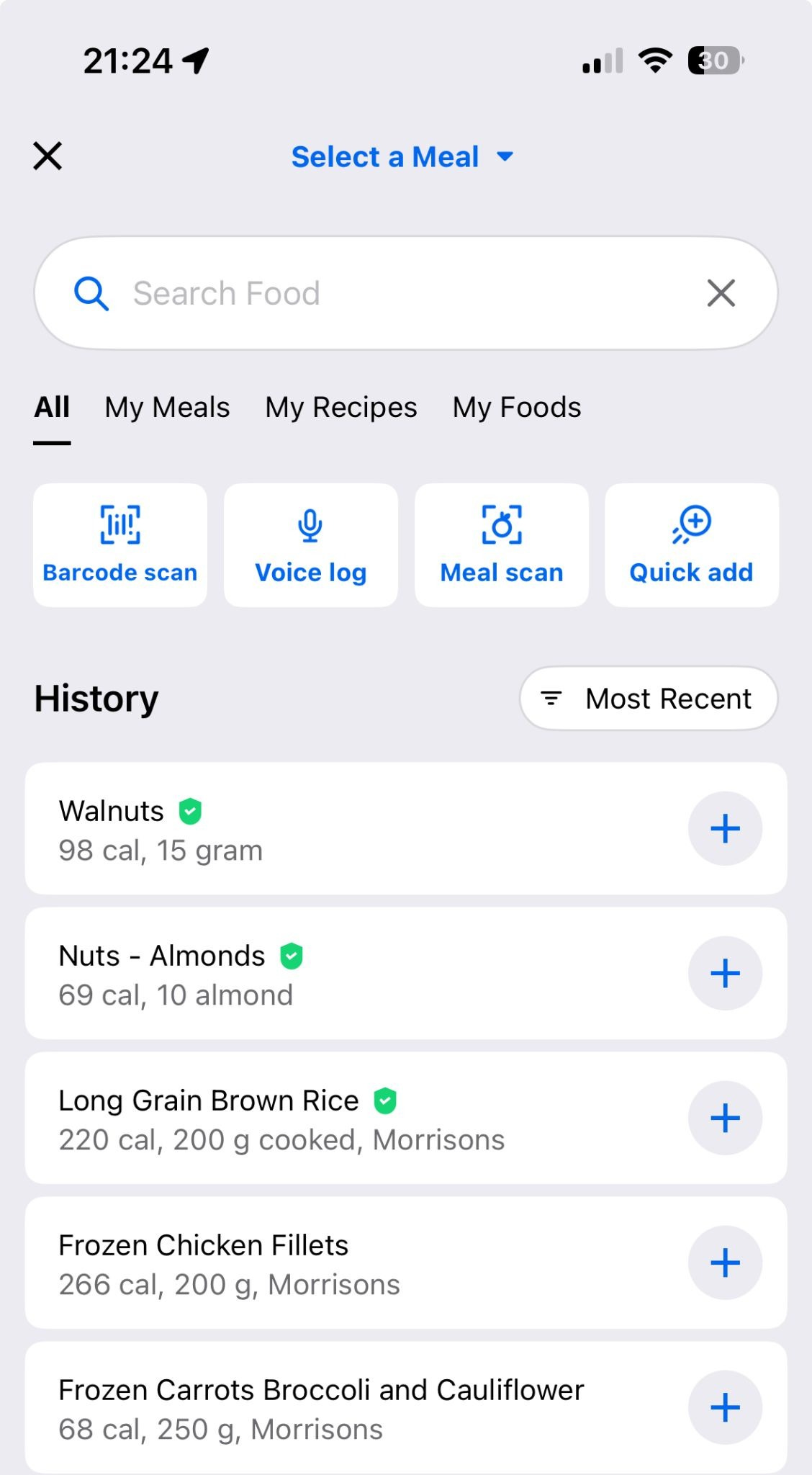

The apps that will survive are the ones that own the hardware, like the Oura Ring, Whoop Band, or the Apple Watch. Or, as Garrett Ruhland wrote in his Linkedin Essay, the inputs. I would expand on this to say the sensory inputs.

Everything in the middle layer, like dashboards, content and logging are dead.

The action-performing layer, or the output, in my view, will also be taken over by agents. They can already book classes and order groceries. Can they potentially re-fill prescriptions? Well, they can go online and pay your grocery bill using your credit card, so they could hypothetically go onto a telehealth website and order prescription medications. The technology now exists, and it’s only a matter of time before the knowledge from hackers and devs from the tech-bro world distills and disseminates to the masses.

Okay, what about Chat GPT Health? Where does it fit into the picture?

Last week, OpenAI launched ChatGPT Health. It syncs with your medical records and allows you to connect to other health and wellness apps, like Peloton and MyFitnessPal. Basically, it allows you to ask questions about your health data. For the average consumer, this is a genuinely wonderful moment and, in my view, will be the unlock millions of people need to understand what on earth is going on with their health.

But make no mistake, ChatGPT Health is a baby step in the direction I’m talking about. GPT can’t read your calendar or schedule your gym class. It can’t nudge you at 9pm and it can’t order groceries. It understands but it doesn’t do.

Some advice

So, what could these consumer health apps do to stay alive? Small start-ups need to ask themselves, seriously, how they could stay in business if no human ever opens their app again. And those companies should probably consider building an agent-native AI health assistant that can form relationships, give contextual health advice and, most of all, be proactive rather than reactive.

For the larger incumbents like Flo Health, MyFitnessPal, and Calm/Headspace? It’s a bit trickier. It could be argued that this essay is very, very early and that the Average Joe will have no idea how to build something like Francesca.

This is an argument I accept.

However, you’re betting on user incompetence and hoping people won’t figure it out. I don’t think that’s a valid defence against this trend. But here’s what I would do: I’d start figuring out how to make my app agent-native friendly, such that everything a human can click on in your app an agent could too. If my app can’t sync up a period-tracking calendar with a daily appointment calendar and symptom checker, I’d maybe figure out how to do that.

Also, I’d start positioning my software offering as a regulated medical device, which may give me an advantage over smaller incumbents who are unwilling to change their model.

The future

Now here’s what I think happens next.

Within a year, every health-conscious person who can afford the max subscription of Claude Opus 4.5 or GPT Codex will have something like Francesca. They might not have necessarily built it themselves, and someone will probably package it for them. The interface will be a conversation mediated through voice notes and text messages, and that means the relationship with your health will be mediated by something that knows you, intimately.

I know this all sounds like science fiction, but science fiction has arrived.

Welcome to 2026.

This evening Francesca sent me another voice note.

“Good evening Ash. I’ve sent you a personalised voice briefing of your week - I pulled your Oura data, correlated it with our calendar, analysed the patterns and narrated it. Let me know if I need to book any appointments for you next week.”

“Thanks,” I said. And then I made dinner.

**The views, opinions, and recommendations expressed in this essay are solely my own and do not represent the views, policies, or positions of any other organization with which I am affiliated. This content is provided for informational purposes only and should not be considered medical, legal or investment advice.**