Watch on YouTube • Listen on Spotify • Listen on Apple

Does the world really need another podcast? I’ve been asking myself this for a few weeks because I’ve been wanting to start my own, and the answer I arrived at was “maybe.”

Podcasting is really hard to do well, takes a ridiculous amount of time, and I’ve never once enjoyed listening to a recording of my own voice.

But what convinced me to go for it was that when I went looking for a GLP-1 podcast that bridged the gap between the medicine and the money, I couldn’t find anything I could really sink my teeth into. The thing I wanted, something like an equity research analyst asking a key expert, simply didn’t exist.

So I thought, okay, I’m going to make this exist.

My first guest is Professor Alex Miras, a world-renowned obesity expert, clinical trialist, and consultant endocrinologist at Ulster University. I met Prof. Miras a few years ago and took an instant liking to him. He’s a straight-talking academic who has absolutely no interest in sugarcoating anything, and in this episode, he challenges several common assumptions that people hold about weight-loss medications.

He made the perfect inaugural guest.

What follows are the three biggest takeaways from our conversation, and there is so much more in the full episode, including discussions on tolerability, the ATTAIN-MAINTAIN trials, maintenance pathways, and where the next generation of drugs is heading.

I recommend listening to the whole thing.

But first…this edition is proudly brought to you by Sacher AI.

Retention is the business problem every D2C weight-loss platform is trying to solve right now. And increasingly, teams are betting on AI coaching to fix it. But the problem is that without genuine clinical depth and experience in this space, you end up with one of two outcomes: an AI agent that plays it so safe it’s useless, or one that crosses lines you didn’t know existed.

Either way, retention doesn’t improve.

Sacher AI is a leading AI consulting firm that I point people to because they’ve solved both sides of this problem. They’ve analyzed thousands of real patient conversations and built systems that know how to retain patients and keep them engaged. Their team includes clinicians who’ve published peer-reviewed research on AI in obesity care.

If you’re building patient-facing AI in this space, talk to Sacher AI first.

1. The drug does the heavy lifting

There’s a fundamental tension in the D2C GLP-1 market between two business models: fulfilling orders for a drug and creating a health platform with comprehensive care.

On one hand you have the online pharmacy model, Amazon-esque in that it ships your prescriptions fast and clinical operations stay hands-off until a customer reaches out with a question. From a business point of view, this model is dominating the market (both in the US and UK) because COGS stays low and gross margins are attractive. This, in turn, keeps retail prices low, which matters enormously in a market where patients are paying out of pocket and are super price-sensitive.

On the other hand you have the wrap-around care model, by which companies prescribe the drug, then layer on coaching and ongoing behavioural modification in hopes of achieving better clinical outcomes and improved retention (thus, maximizing the lifetime value of each customer). The key question is how much do customers actually value wrap-around care? Are they using it over the long term, and how much are clinical outcomes improved by it?

Prof. Miras reframes this question by quantifying the clinical evidence directly.

Of the weight loss patients achieve, how much is coming from the behavioral intervention versus the drug?

“Without a doubt, the drug works. And that’s not my opinion. If you look at the clinical trials, the placebo group loses 2.5% of body weight. The drug group loses 22.5%. You can make a pretty solid conclusion that the 2.5% comes from the behavioral intervention and the 20% comes from the drug. . . . What the drug will do is it will reduce the amount of food you eat. It may not—or, more likely, will not—change what you eat. The ‘what you eat’ depends on dietary support. Some people may already know this. They may even have a good quality of food, but there’s just too much. “

“We, even us in the field of obesity care, some of us keep stressing this myth of the importance of the multidisciplinary team. The multidisciplinary team is there for people that need it, but not everyone needs to see the multidisciplinary team by default. . . . If we want to make these things scalable, you cannot give everything to everyone. Number one, it is not necessary. Number two, it is very expensive.”

Prof. Miras is speaking from a clinical and public health perspective, but he’s explicit that the principle applies to both public and private settings.

From an NHS standpoint, the idea that every patient gets full multidisciplinary wrap-around care with ongoing nutritional, dietary, behavioral, and psychological support is simply unfathomable at scale. And what the private market has shown us is that most consumers underestimate the level of agency they have over their own health.

In D2C, the constraint is slightly different. Wrap-around care comes at a hefty premium, and the question becomes whether patients value it enough to pay that premium, especially when the clinical evidence says the drug itself accounts for the vast majority of weight loss. And for patients hoping that wrap-around care might replace the drug long-term, Prof. Miras is unequivocal: Obesity is a chronic disease, and weight regain after stopping the drug is “the default, not the exception.”

Many things are changing at once, so it will be interesting to see what happens next in the market. First, more drugs are entering the market with different mechanisms and efficacy profiles, including new oral and injectable options.

That complexity will generate clinical questions that patients can’t answer on their own: Which drug suits my profile? Should I switch? What does maintenance look like? Can I switch to an oral now that I’m done with injectables?

My expectation is that this will drive up contact rates, and the companies that have priced in 24/7 clinical support will be better positioned than those that haven’t.

Second, GLP-1s are commoditising. As more telehealth companies enter the space, prices are falling and the drugs themselves are becoming harder to differentiate. When every provider can offer roughly the same molecule at roughly the same price, patients will choose based on some other factor.Whether that factor turns out to be brand, clinical support, or something we haven’t anticipated yet remains to be seen.

I don’t have a clean answer on whether wrap-around care will prove to be the differentiator. What I’m fairly confident about is that the right kind of clinical guidance will matter more than it does today.

2. In the global market, price is still the only thing that matters

Oral GLP-1s have been selling like hotcakes since launching in the US, and it’s led many to believe that oral tablets’ market share will be far higher than analysts’s expectations, including my own. Prof. Miras still expects injectables to remain dominant, somewhere around 60-70% of the market over the next five years, with the cheaper oral versions taking the remainder.

But the more interesting point is that pricing is still the determining factor on whether or not patients get treated at all.

“Price will determine whether these medications will become popular because we’re not talking about just the UK here. We’re talking about millions and millions of people around the world. And if you offer something which is scalable, it can become popular even if the efficacy is not as good as the injectable.”

“There’s no harm in starting with the tablets. Certainly, if finances are an issue and if someone is lucky enough to be a super-responder at a lower cost, fantastic. But if you’re finding that you are not achieving the health benefits that you want, then you might want to move on to the injections.”

One of the concerns I hear is that orals will cannibalise injectable sales for Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly. That’s a reasonable worry, but I think the more interesting perspective is how orals might actually function as a GLP-1 funnel.

As Prof. Miras mentions, some patients will respond exceptionally well to orals. They’ll be “super-responders,” losing as much weight on a tablet as others lose on injectables:

There’s a wide variability of response. There will be people on Orforglipron that won’t lose 12, 14% of their body weight. They’ll lose 20%, 25% of their body weight. These people exist. You try the drug for about four months or so, and then you can gauge whether someone is a good or a suboptimal responder.

For those patients, that is simply fantastic, but others won’t achieve the weight loss they’re looking for, and they’ll turn to injectables to upgrade. Prof. Miras gives roughly a four-month window to gauge that response on the tablets.

I think that’s a great way to think about how the market might shape up over the coming months, especially with Orforglipron entering the picture. Because Orforglipron is a small molecule, not a peptide, the API manufacturing process is substantially easier and requires lesser doses of the active ingredients.

That could make it significantly cheaper than oral Wegovy over the long run, which would push the price floor even lower and potentially widen the top of the funnel even further.

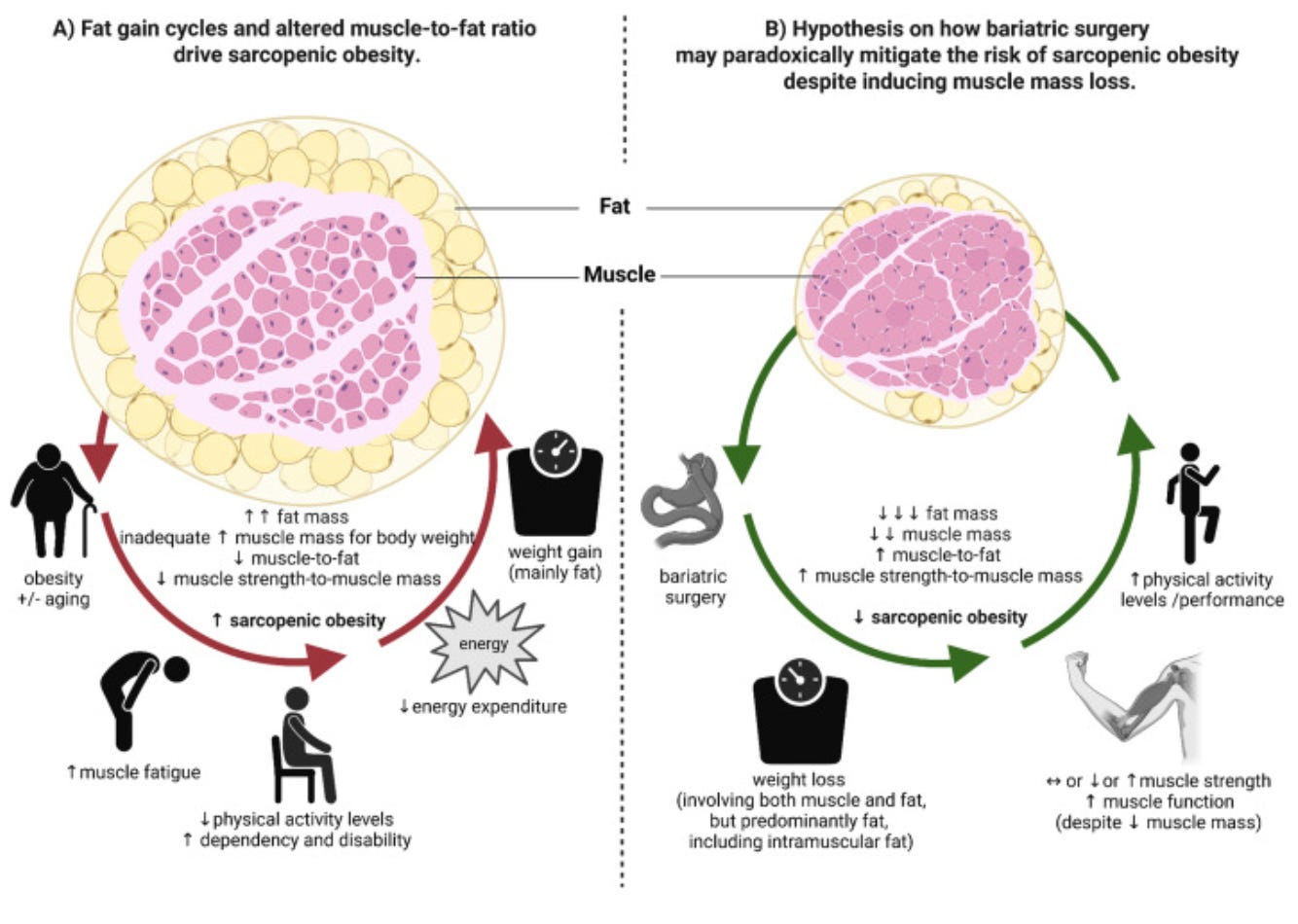

3. The muscle-loss panic is probably a measurement problem

Muscle loss has been one of the loudest criticisms of GLP-1s. The media has made enormous noise about it, and several pharma companies are building entire pipelines around preserving muscle mass on these drugs.

Prof. Miras is sceptical that the problem is what we think it is:

There is a muscle mass loss, but functionality goes up. You cannot diagnose sarcopenia if someone's function improves. You need lower muscle mass and lower muscle function. And we're seeing them going in different directions. . . . It might be that the way that we measure muscle mass is the problem. And people are actually not losing muscle mass, but they're losing fat from their muscle. And therefore it appears that the muscle is less.

There are two points here that I think are important for anyone investing in or building around the muscle-loss narrative.

First, DEXA scans are the tools most commonly used to assess body composition, and they cannot distinguish actual muscle tissue loss from intramuscular fat loss (fat that surrounds the muscle). So, when a scan shows less muscle mass after weight loss, it might be showing muscle getting leaner, i.e., losing the fat that surrounds the muscle, and not the muscle itself.

Prof. Miras notes that while muscle mass goes down on scans, patients are getting stronger, more mobile, and more physically capable. This may mean that a leaner muscle is actually a better functioning muscle.

Second, several pharma companies are positioning anti-myostatin drugs as a fix for GLP-1-induced muscle loss. While this is certainly interesting and I'm keeping a keen eye on what happens over the next year, what they will need to prove is that these drugs also improve muscle function. There is no compelling data that suggests they do this just yet, and until that happens, we have to be cautious about what increased muscle mass actually means when it comes to these drugs.

**The views, opinions, and recommendations expressed in this podcast and essay are solely my own and do not represent the views, policies, or positions of any other organization with which I am affiliated. This content is provided for informational purposes only and should not be considered medical, legal or investment advice.**