Why Britain’s GLP-1 Patients Are Paying for America’s Drug Politics

1.5 million become collateral damage

When I was 14, I spent my weekends binge-watching Breaking the Magician's Code on Sky TV. My teenage brain learned that all great magic can be boiled down to one thing: misdirection. Wave your left hand in the air while your right hand pulls off the trick.

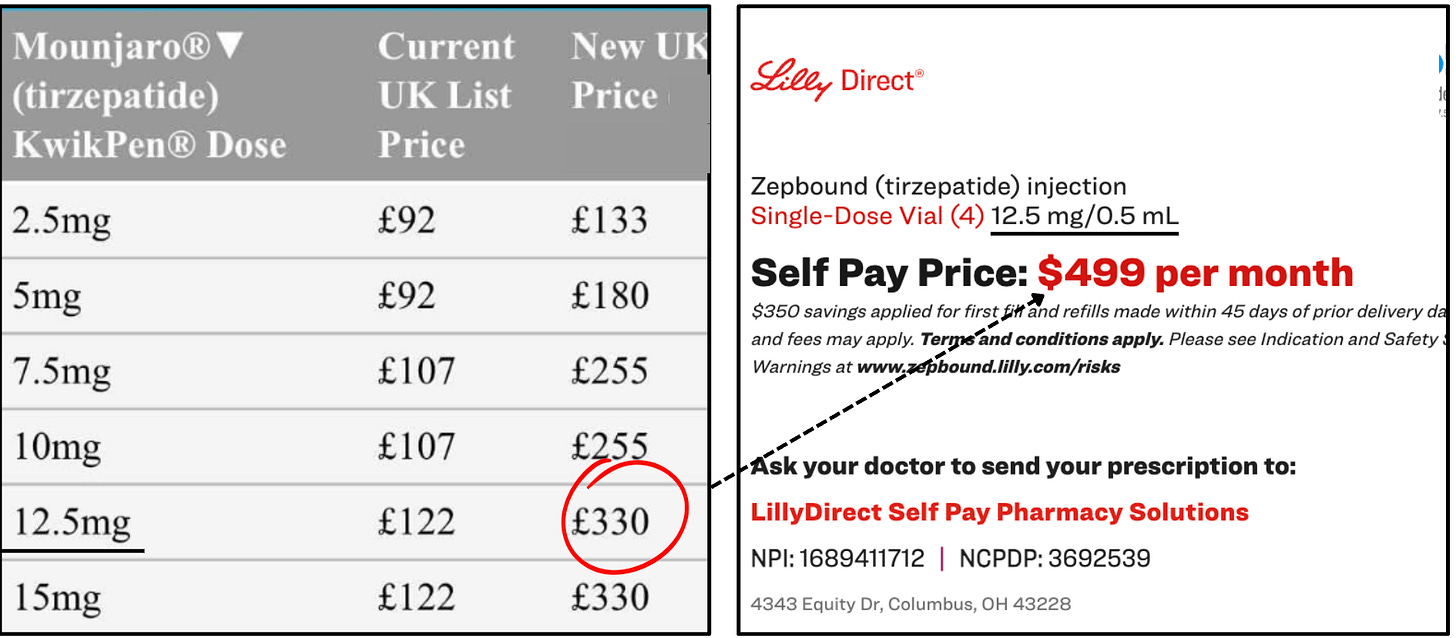

September's 170% price hike for Mounjaro in the UK is the same type of misdirection.

American audiences might see the headlines and assume this means cheaper drugs back home. In reality, nothing has changed: The NHS won’t pay a penny more. The U.S. patients won’t pay a penny less.

The only people whose pockets will get lighter are British private patients staring down at a £330 invoice.

The Reality

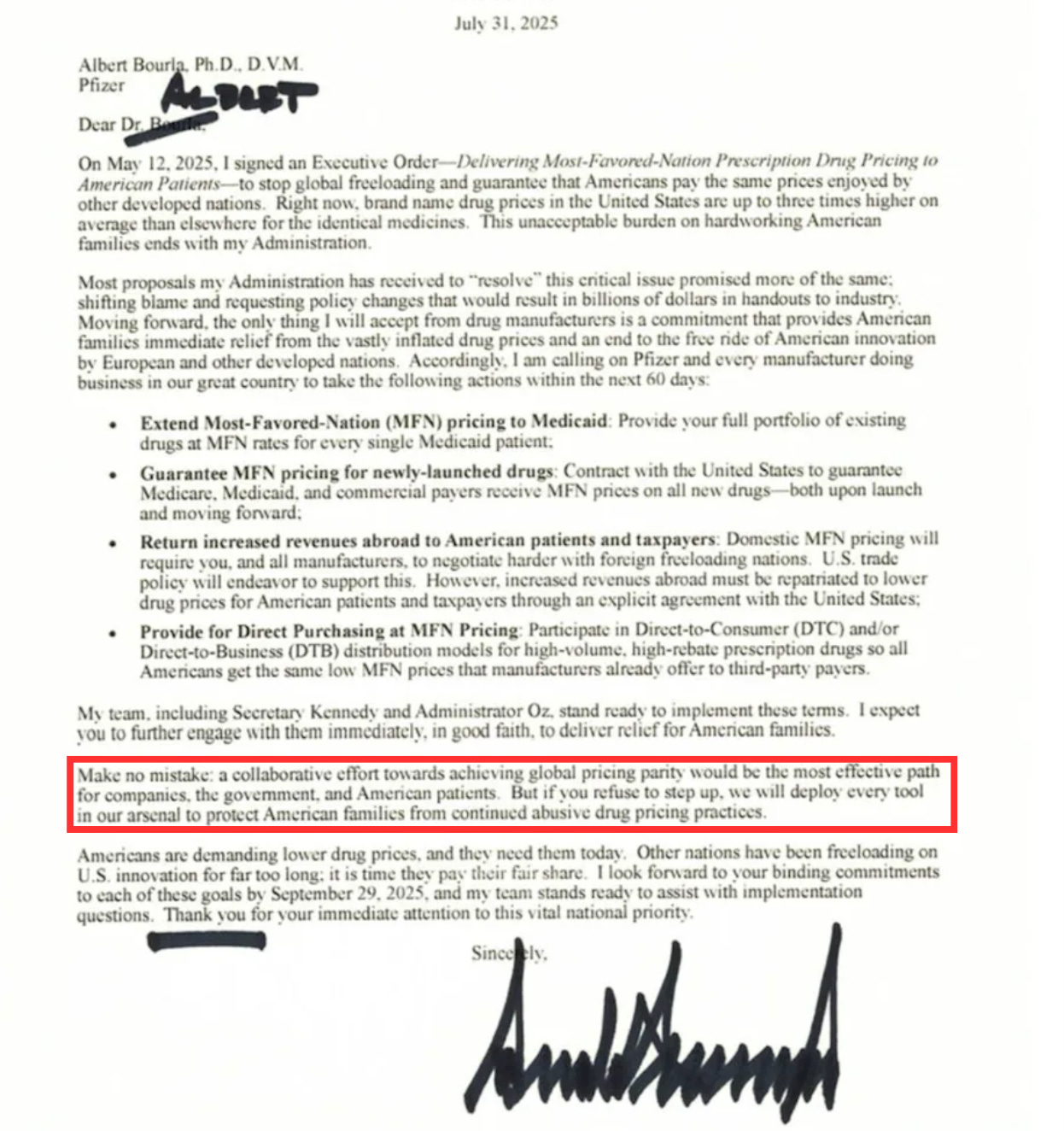

Lilly’s move is a response to political pressure from Donald Trump, who in July gave the CEOs of 17 major pharma companies — including Lilly and Novo— 60 days to lower U.S. drug prices by aligning them with the list price of developed nations.

Or else.

Or else what? Trump never specified. So, like something out of The Godfather, the ambiguity was kind of the point.

Lilly's response was to give him the optics he wanted by changing the number Trump could see, not the one that mattered.

The list price—Trump's number—is the price of the drug before any rebates or discounts are applied. The real price—the net price—is negotiated in secret, especially with buyers who have leverage.

As the single payer for prescription drugs for nearly 70 million people, the NHS has enormous leverage. For Mounjaro to be used at scale, NICE must judge it cost-effective at the list price. If it doesn’t, Lilly faces losing the entire UK market, so it’s expected to offer confidential rebates and discounts that bring the net price down to a level the Treasury will actually accept.

Even with Mounjaro's price jump, the NHS will shrug its shoulders. Its confidential rebates will stretch further, keeping costs flat—or as drug-pricing expert Bryce Platt told me:

"The UK is now getting a much bigger discount.

Unlike Britain’s single negotiator, America has thousands of insurance plans working through a handful of PBMs who negotiate drug prices. Those multi-year locked in deals aren’t suddenly going to change because the UK list price moves. It’s absurd to even think it would.

So American patients will keep paying what they’ve always paid.

If Washington really wanted to move the needle for US pricing, it would stop fixating on list prices in Europe and other developed nations and, instead, start demanding Britain’s deal. Get the NHS-level discount applied to U.S. contracts and then make them public.

The Mechanics

The new price tag of Mounjaro is roughly on par with what Americans pay out of pocket through LillyDirect’s cashpay channel. That gives David Ricks, the CEO of Eli Lilly, a big, visible number to point to when asked how the company is narrowing the gap between U.S. and foreign drug prices.

The irony, of course, is that instead of lowering U.S. cash-pay prices, he just raised Britain’s and handed policy hawks a soundbite to sell to their voters.

The optics may indeed play well in Washington, but in Britain, the consequences are pretty devastating. Around 1.5 million people are now on GLP-1s, and roughly 90% get them through online pharmacies.

Unlike the NHS, these private providers have little bargaining power.

Most buy at list price through wholesalers like Alliance or AAH, who might offer a tiny sliver of discount. When Lilly raises that list, the cost flows down the value chain — wholesaler to pharmacy to patient — with pharmacies adding their own margin to survive.

In theory, I think the largest-volume players could cut deals with Lilly and keep prices competitive, creating a winner-takes-all market because the vast majority of smaller providers don’t have that kind of muscle.

The discounts will probably be fragile, though, since Lilly can pull them back at any moment.

On the whole, the list price hike feels like Armageddon, not just for the private market, but, more importantly, for the patients who depend on them.

The Victims

At £330 a month for the higher doses, hundreds of thousands of people are going to be forced off treatment. On a median post-tax salary of about £2,400, Mounjaro’s new price would eat nearly 14% of monthly income, which is roughly the size of a car-payment or a portion of council tax. For a price-sensitive market like GLP-1, that is just not sustainable in any way, shape, or form.

What about Wegovy?

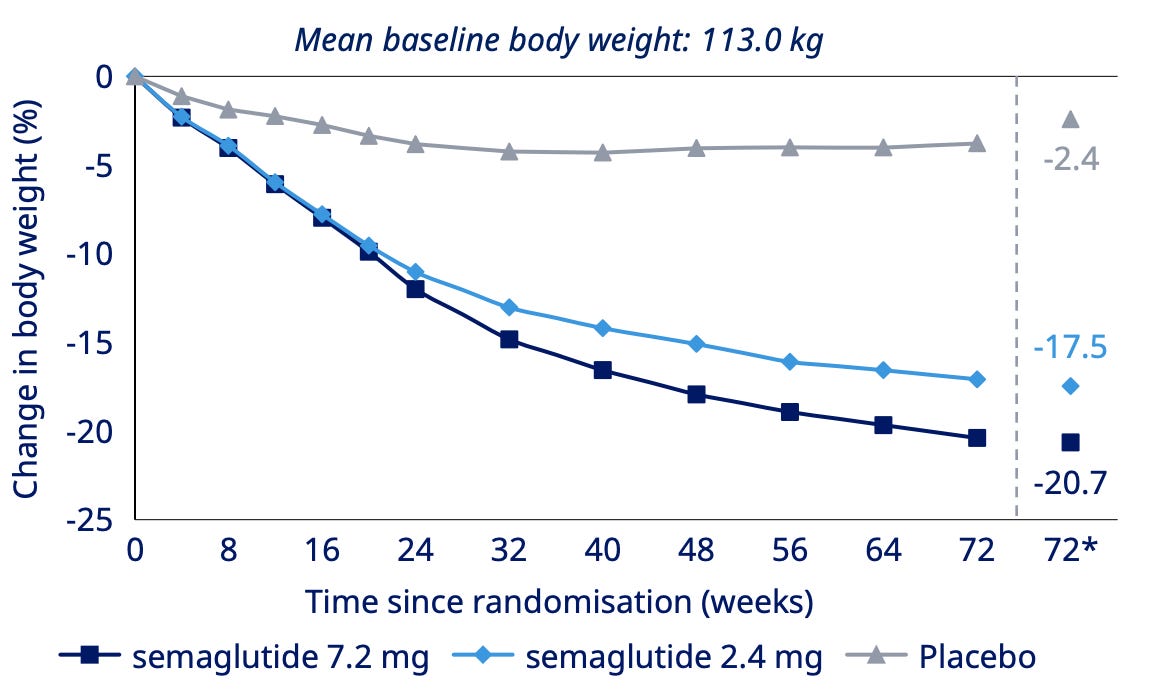

Private providers are already steering patients toward Wegovy. On paper, yes, it looks like the obvious choice. The new 7.2mg dose narrows the placebo-adjusted weight loss gap to just a few percentage points against Mounjaro, which’ll make it highly effective.

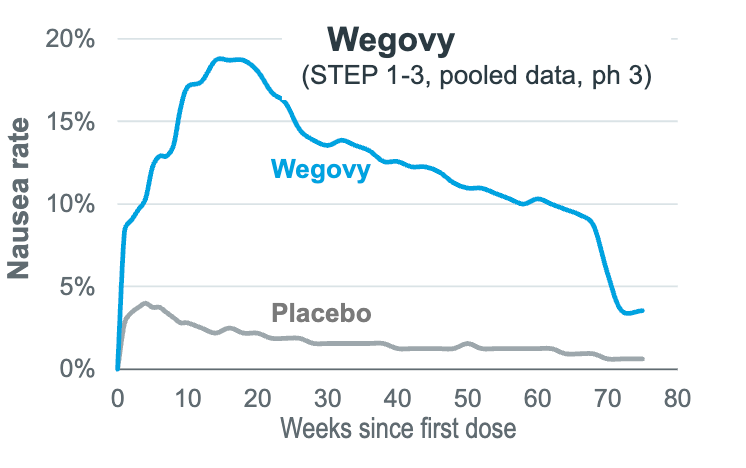

Weight loss is good, but the issue will be side effects.

Mounjaro has the best side-effect profile on the market, bar none. Going from a drug that has best-in-class tolerability to a drug that doesn’t is going to be rough for many people.

And in particular, I worry about the vomiting rates, which is about six percentage points higher on Wegovy than on Mounjaro. That’s a big red flag.

Vomiting is the side effect most likely to drive patients off treatment and cripple retention.

It’s going to be even more important to be upfront and remind patients that these types of GI side effects usually show up when the dose is increased, and fade after a few weeks as the body gets used to the medication.

In blunter words, you kind of need to push through it.

The Alternative

But this all assumes Novo Nordisk can actually meet a sudden surge in demand. I would argue that’s far from certain.

Wegovy has already faced repeated shortages, and scaling API production takes months. If we assume 1 million people are on Mounjaro and estimate that 35% of them will make the switch… Novo needs to prepare for 350k monthly subscriptions in the space of 2-ish weeks.

If supply can't keep up, providers will fall back on older GLP-1s like liraglutide, which is a daily jab for only 4-6% placebo-adjusted weight loss after 12 months. Disappointed by the weaker results and daily injections, I think many patients will simply quit or turn to unregulated channels, like they've done in the US.

Then there’s the very real strategic risk.

For two years, Novo has been quick to follow Lilli but slow to execute. First it was behind on D2C cashpay channels, then vial launches and then telehealth partnerships.

Now that Lilly is first again in placating Trump's demands and stealing the optics, I find it very difficult to imagine that Novo Nordisk won’t follow suit. After all, they both received the same 60-day ultimatum from Trump.

So, in the short term, I anticipate that Novo might enjoy a reasonable sales tailwind from the UK market, but over the medium to long term, the price floor for GLP-1s could rise across the category.

For online providers, this is now an existential test.

Large, diversified players can offset the UK hit with growth in earlier-stage GLP-1 markets abroad. Smaller UK-only operators, running on thin margins and with little leverage over wholesalers or Lilly, will be forced to rethink their strategy or shut down.

Conclusion

In the end, it’s the patients who are hit hardest. Scroll through Reddit, and you sense the real tragedy of people who are being forced to quit life-changing medications because of a couple of headlines.

'Can't afford it anymore. What do I do?'

'Try the black market.'

'Maybe if I take half doses?'

Literally collateral damage to political theater.

If there’s any silver lining, it’s that moments like this create political pressure. The longer the NHS relies on staged rollouts, the louder the calls will get for Wes Streeting to accelerate partnerships with online providers for a faster rollout of GLP-1s to the public.

In the meantime, when you see a headline about drug companies narrowing the price gap, look a little closer. What is the misdirection? And who, actually, pays the price to maintain it?

**The views, opinions, and recommendations expressed in this essay are solely my own and do not represent the views, policies, or positions of my employer or any other organization with which I am affiliated. This content is provided for informational purposes only and should not be considered medical, legal or investment advice.**

If the reason UK pays less is because of the negotiating leverage of the NHS, then why was the cash-pay (non-negotiated) UK price so much lower than the U.S. cash price?

Really interesting article. I wonder if there has been a large drop off now the effects have come into place. My suspicion is people have just accepted it. A bit like a Premier Inn hotel room; it’s extortionate, it’s ridiculous but…