When GLP-1s become brain drugs

Doors are opening for Alzheimer's patients, for Novo, and for... Regeneron?

In the next few months, the EVOKE trials will show the cleanest readout yet on whether GLP-1s can slow Alzheimer's disease. If the results are positive, every analyst and their mother will be shouting how "oral semaglutide cracks open the Alzheimer’s market”.

Yeah, that's the obvious first-order effect, but you and I like to think a little more into the future.

Oral GLP-1s cause weight loss, and for Alzheimer's patients — who are already at increased risk of frailty — that weight loss includes dangerous muscle mass loss. Losing muscle will make these patients even more frail and increase the risk of falls and hip fractures, which’ll accelerate the cognitive decline we’re trying to prevent.

These unwanted side effects present a massive opportunity for Regeneron, who happen to be sitting on exactly the right drug at exactly the right moment.

But the extent of their success depends on what happens with EVOKE.

So let's start there.

Why the EVOKE trials are important

The big idea with EVOKE and EVOKE+ is power and clarity.

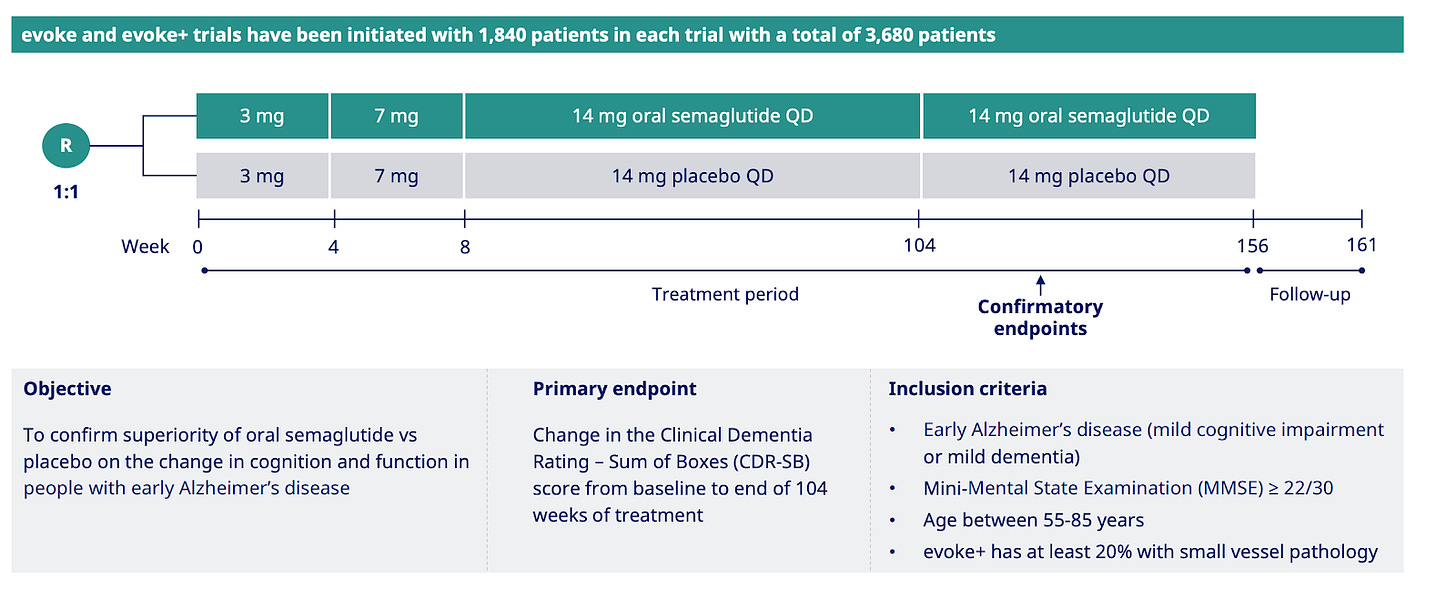

In these two Phase 3 studies (n=3,680 total), patients are randomized to placebo or oral semaglutide in a 1:1 ratio and assessed using the CDR-SB at 2 years, with follow-up of up to 3 years.

This is the definitive test of whether GLP-1s can slow cognitive decline in early Alzheimer's, as the trials are large enough with long enough follow-up time to tell real treatment effect from noise that has really clouded smaller, shorter studies.

But what does 'slowing cognitive decline' actually mean in human terms?

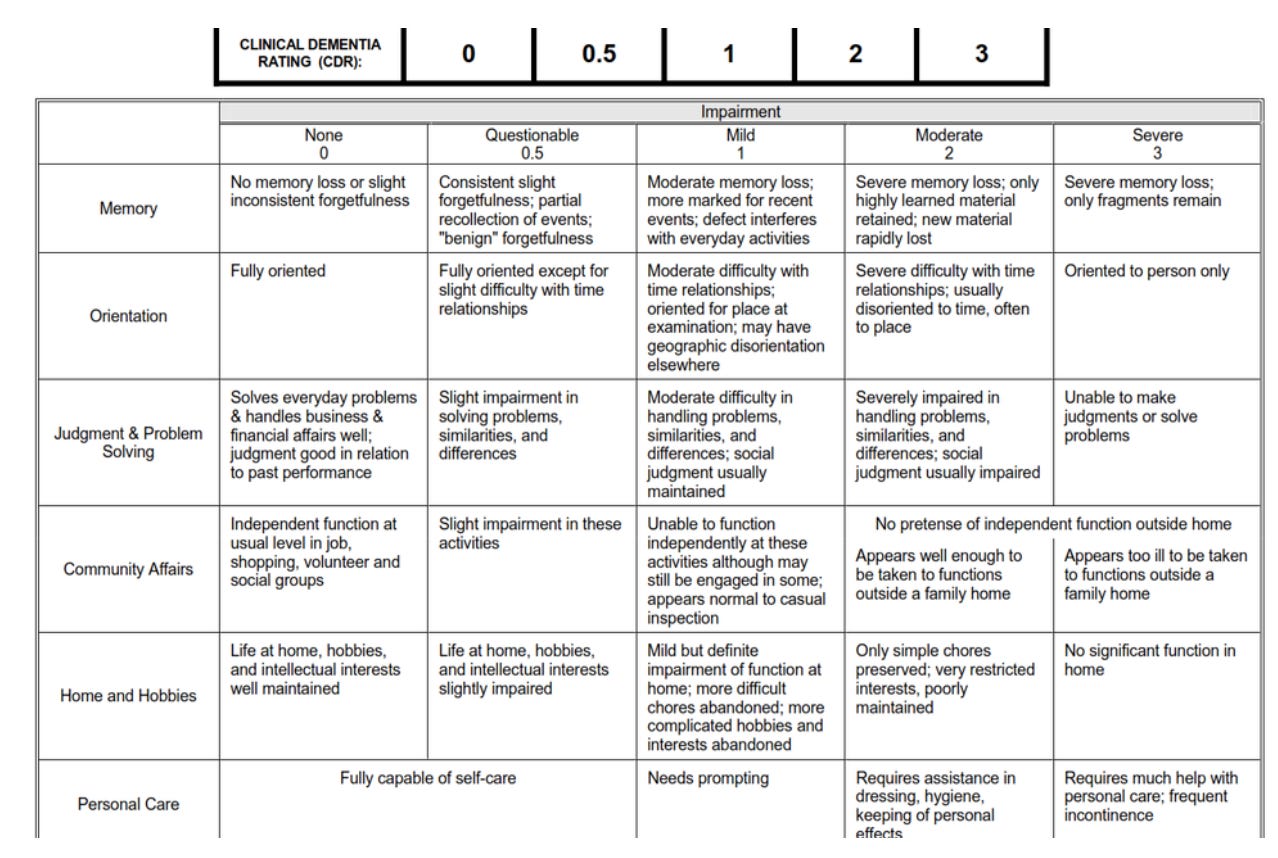

CDR-SB is the Clinical Dementia Rating Sum of Boxes — a single score that measures how well someone with Alzheimer's can think and function in daily life.

Researchers interview both the patient and a family member or caregiver, then rate six key areas: memory, knowing where they are in time and place, judgment and problem-solving, etc., and these ratings are added up to arrive at a score between 0 and 18.

Higher numbers basically mean worse function.

To appreciate what oral semaglutide needs to achieve, we need to understand what passes for innovation in Alzheimer's treatment today.

Our current gold-standard drugs do not cure the disease or stop it. They only slow Alzheimer's progression by roughly one-quarter to one-third compared to placebo. In my opinion, this is a miserable return on investment given the billions invested and decades spent chasing tails on the wrong hypotheses!

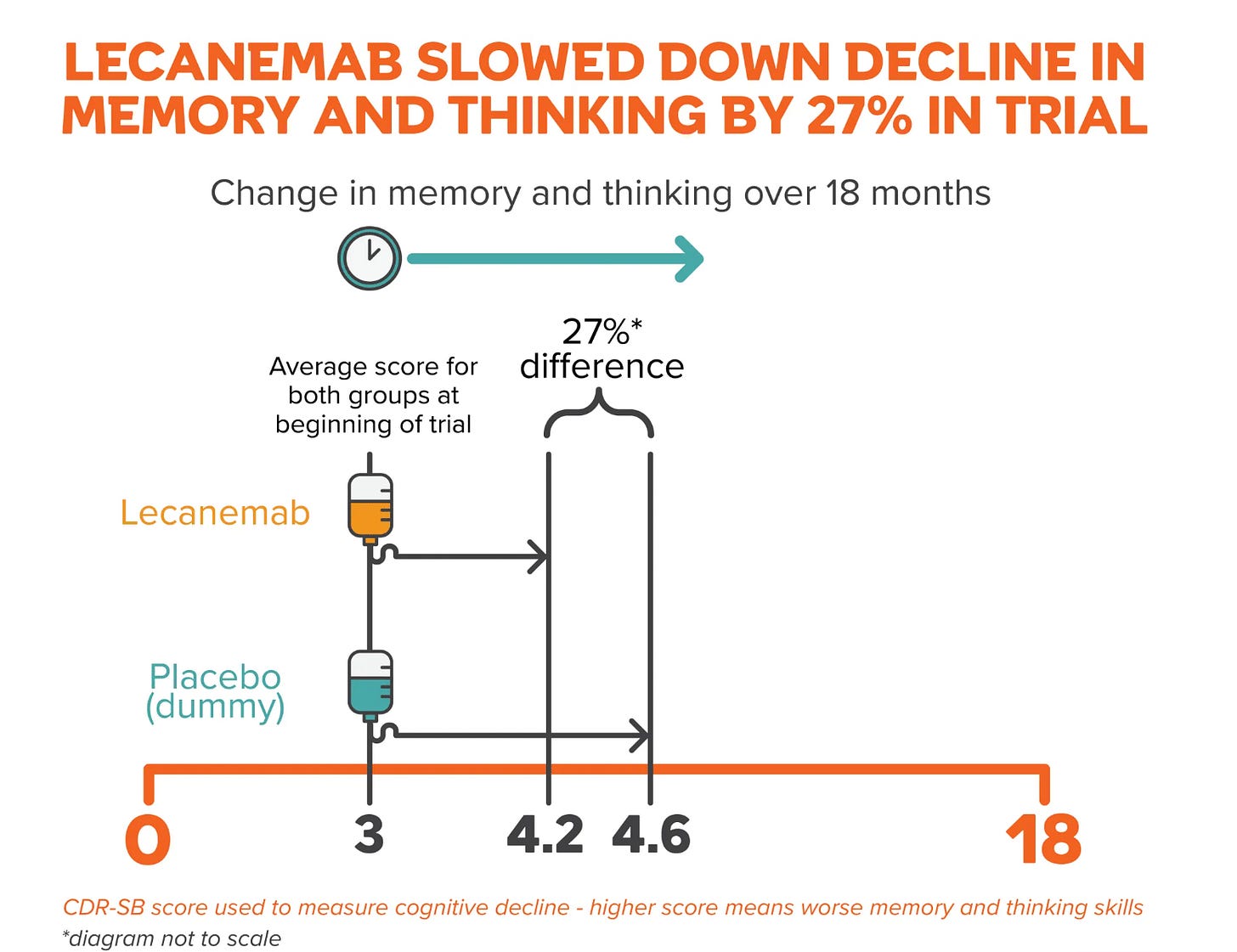

To put that into more concrete terms: on the 0 to 18 CDR-SB scale, lecanemab, a monoclonal antibody that’s not approved on the NHS (because of cost) but is approved by the FDA, showed a 0.45-point advantage at 18 months, which is about 27% slower than placebo.

Donanemab, another controversial drug which costs about £60-80,000 per year, shows a 0.7 point difference at 76 weeks, which is roughly 33% slower than placebo. Both of these drugs require repeated IV infusions and MRI scans to monitor for serious brain side effects, which, of course, adds to the overall cost and clinic time for physicians.

So, if oral semaglutide shows a CDR-SB difference in the same ballpark as lecanemab or donanemab, the cost and complexity savings will be absolutely humongous.

Later this year (or perhaps, even this month), don't look for a miracle! Look for 0.5 to 0.7 points on CDR-SB — roughly a 25-35% slowing because Sema just needs to match the mediocre bar for success.

Anything above that and Novo's stock goes up like a hockey stick.

The likelihood of GLP-1 success

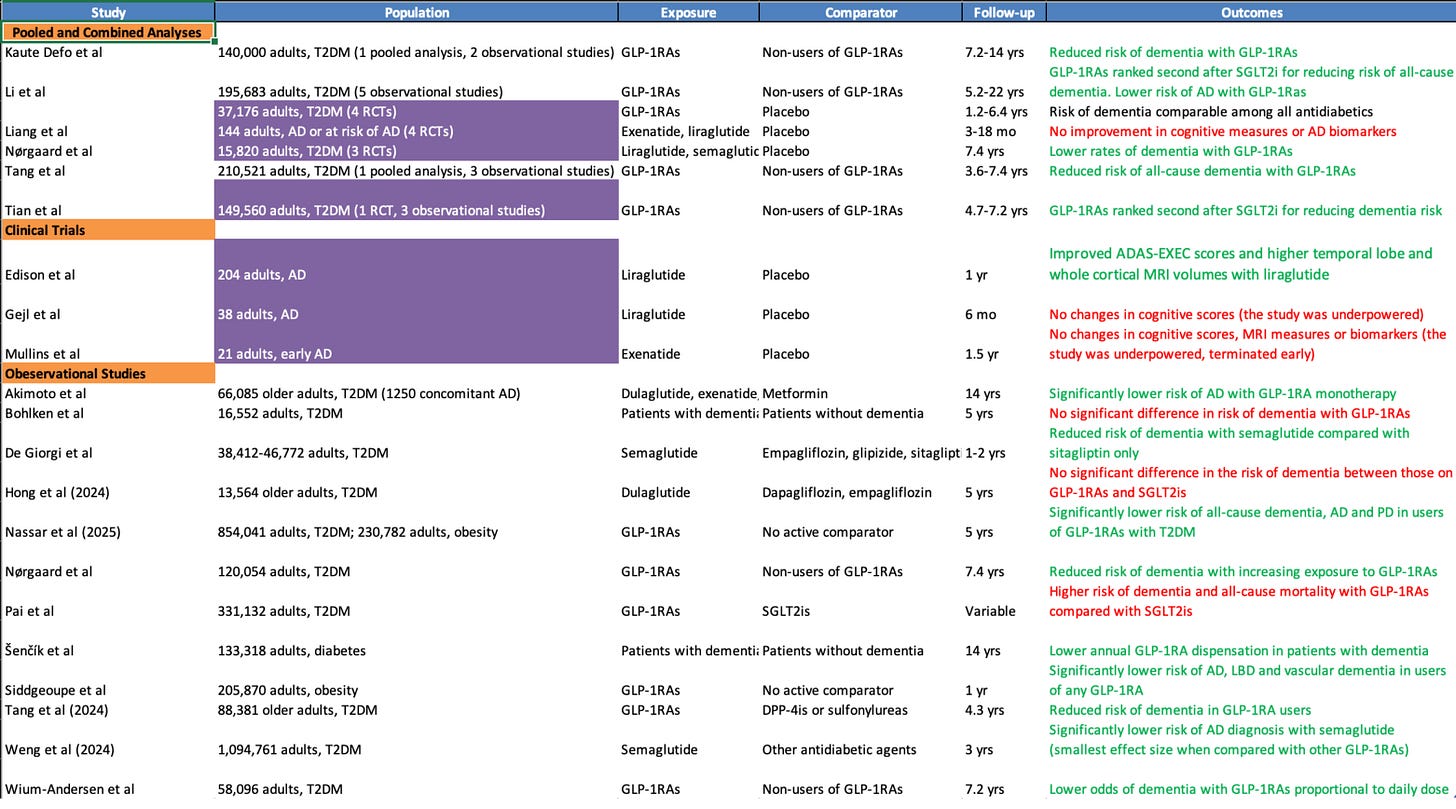

Five out of six major pooled analyses suggest GLP-1s significantly lower the risk of dementia and Alzheimer’s.

One pooled analysis of three RCTs conducted by Nørgaard et al estimated about a 53% lower dementia risk on liraglutide or semaglutide versus placebo. The important caveat here is that there were very few events overall in the study — 15 on drug treatment vs 32 on placebo — so we need to treat this more directionally.

Other, smaller trials in patients who already have Alzheimer’s point both ways, with Edison et al reporting better executive scores and less temporal and whole-brain atrophy on liraglutide, while Gejl (n=38, 6 mo follow-up) and Mullins (n=21, 1.5 yrs follow-up) were neutral to negative, which is exactly what you expect from studies that are short, and not powered to read a slow, insidious disease.

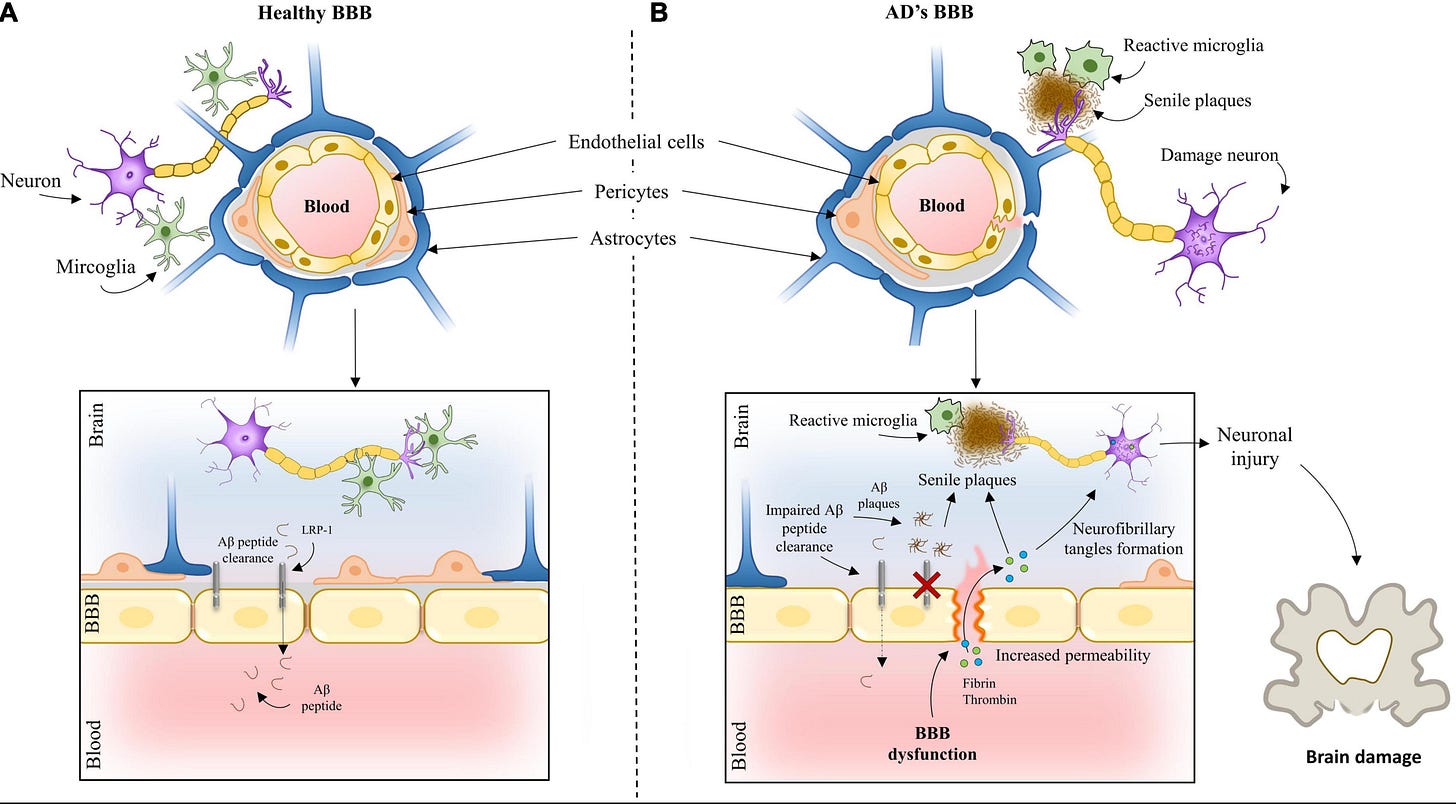

If we zoom in on the goings on of the brain, we’d see that Alzheimer's begins with widespread chronic inflammation, often years before any symptoms appear. As this progresses, the protective blood-brain barrier (BBB) starts to break down like a filter becoming more porous over time. This allows harmful molecules to seep in, but also prevents the brain from efficiently clearing out cellular waste. Meanwhile, damage to tiny blood vessels reduces blood flow to critical brain regions and slowly starves neurons of the oxygen and nutrients they need to function.

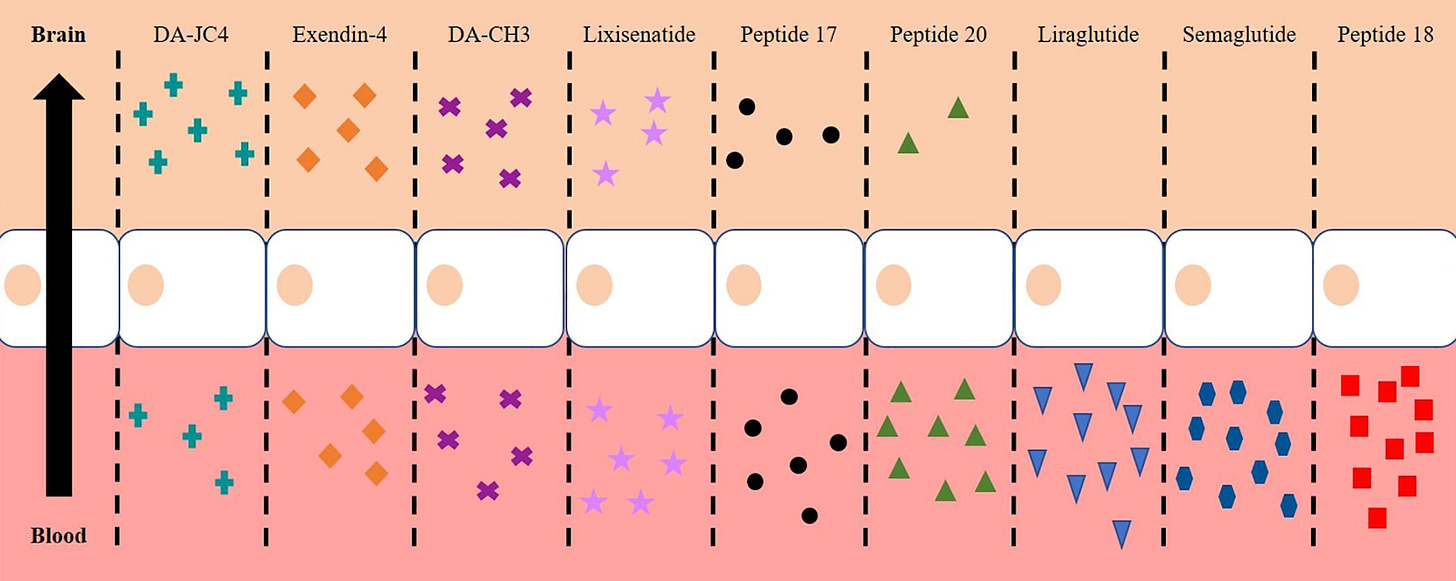

However, will oral semaglutide need to get through the blood-brain barrier to impact brain activity? We don’t know yet, and animal studies suggest they don’t cross the BBB.

But if sema does enter the brain cells in humans, then any benefit will include direct actions on the neurons themselves.

If it doesn’t, I still think it can affect the brain through other potential routes.

First, the brain has gateway regions such as the area postrema and the arcuate nucleus that sit outside a tight barrier and can sense circulating GLP-1 signals. Second, GLP-1s improve inflammation, microvascular health, and insulin signalling in the body in ways that support brain networks indirectly.

Therefore, the scientific justification of sema’s success is still high.

What about tirzepatide? Interest is even higher because it targets both GLP-1 and GIP receptors, and some preclinical work with dual agonists suggests they can cross the blood-brain barrier. There is no human proof, however, that tirzepatide does this, so treat this as mere speculation on my end.

What we do know for certain is that GLP-1s will lead to weight loss — and this isn’t always good news for those with Alzheimer’s.

The sarcopenia constraint in older patients

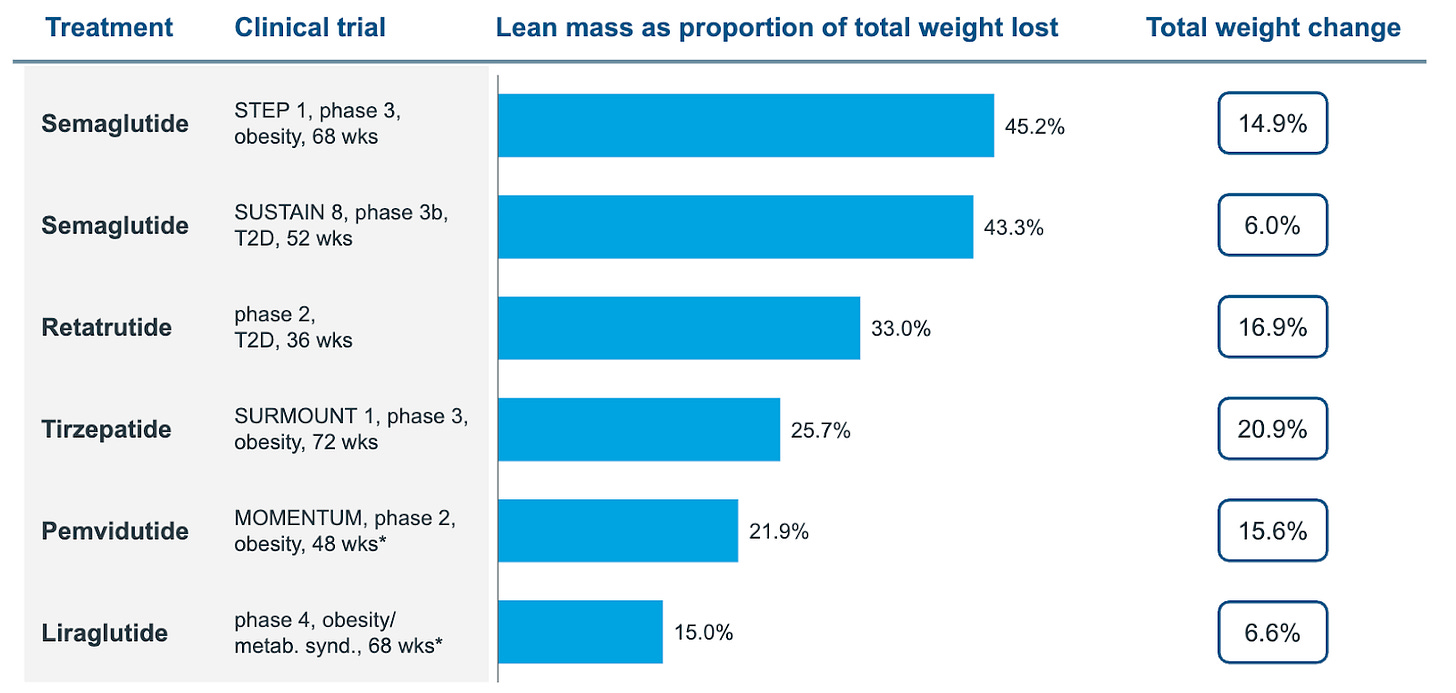

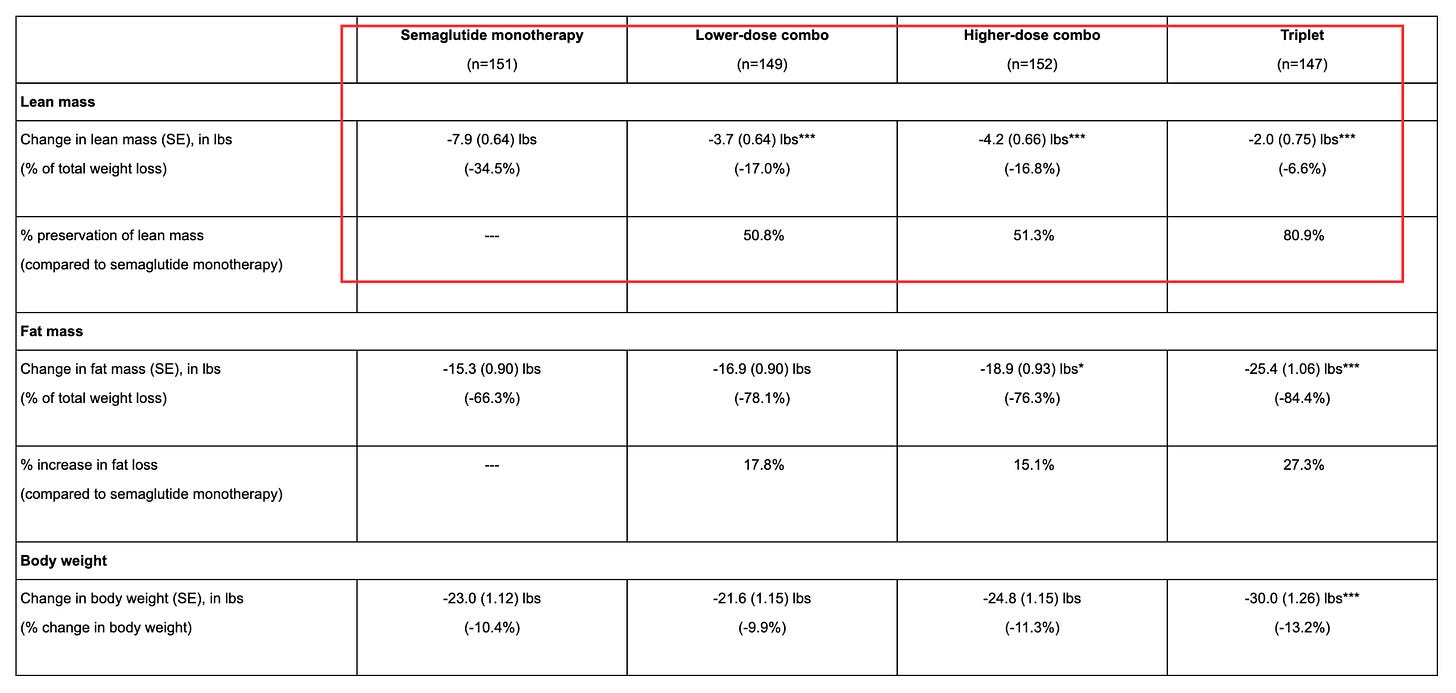

GLP-1s change body composition as well as weight, and that matters more with age because reserves are lower to start with. Nearly 45% of the weight lost on semaglutide is lean mass.

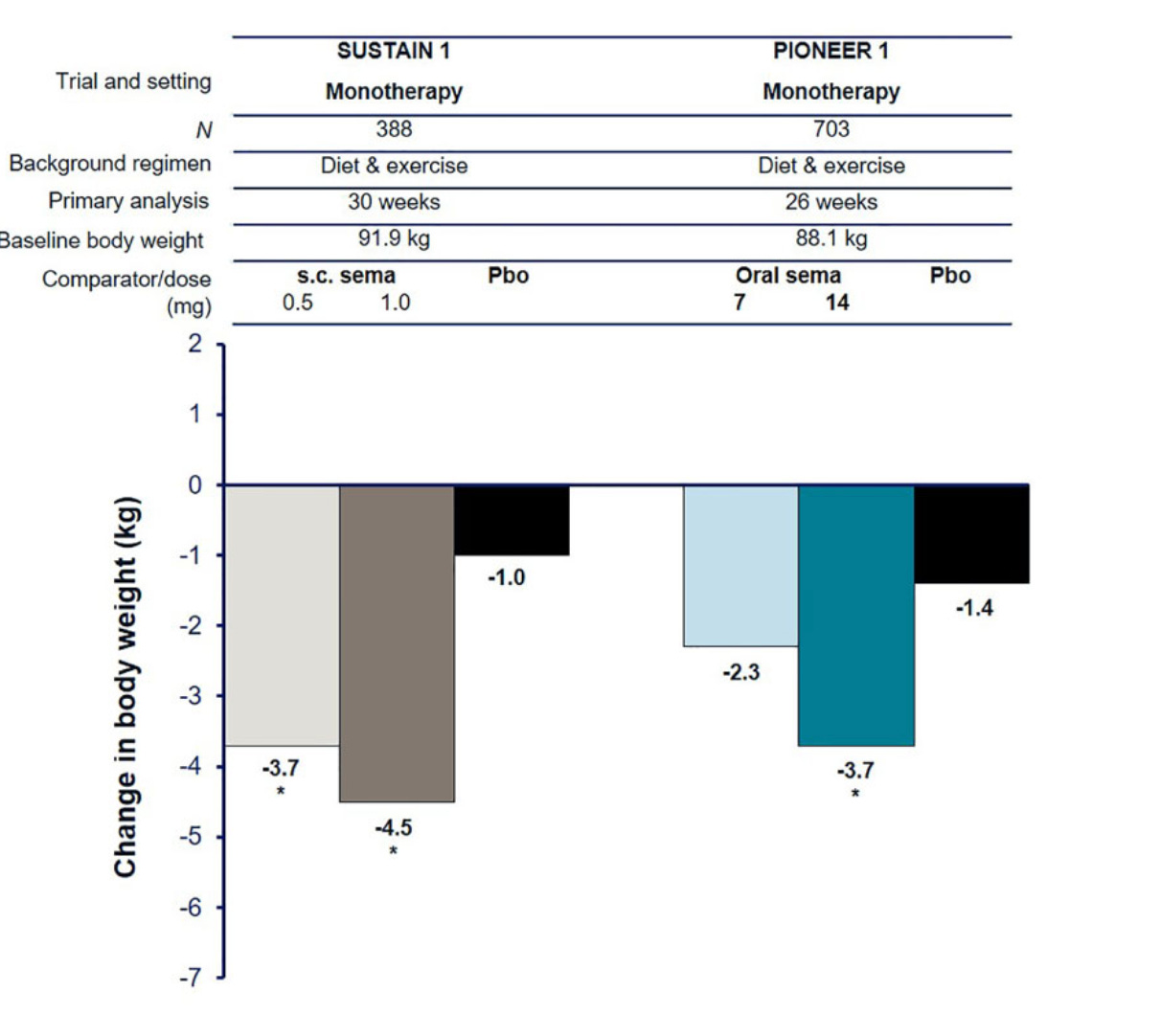

If we treat 14 mg oral as roughly comparable to 0.5 mg weekly injectable Ozempic for orientation, then an older patient on oral tablets loses about 3.7 kg over the 30-ish weeks (bear in mind, evoke trials are 2 years long), and if around 45 percent of that loss is lean mass (or thereabouts) that is about 1.7 kg of muscle gone.

For someone already close to frailty thresholds, a 1 to 2 kg hit to lean mass can dramatically reduce chair-stand time and raise the fall risk, which is why the quality of weight loss becomes extremely important in these patients.

The case for Trevogrumab

And this is where Regeneron comes in to save the day.

Their strategy is to improve the quality of GLP‑1 weight loss by blocking myostatin — which is a natural brake on muscle growth — so that when semaglutide reduces appetite and weight, the body does not give up as much muscle along the way.

In the COURAGE Phase 2 interim analysis, the company reported that about thirty-five percent of semaglutide‑induced weight loss reflected lean mass loss. Adding trevogrumab preserved roughly half of that lean loss at lower doses and more than half at higher doses.

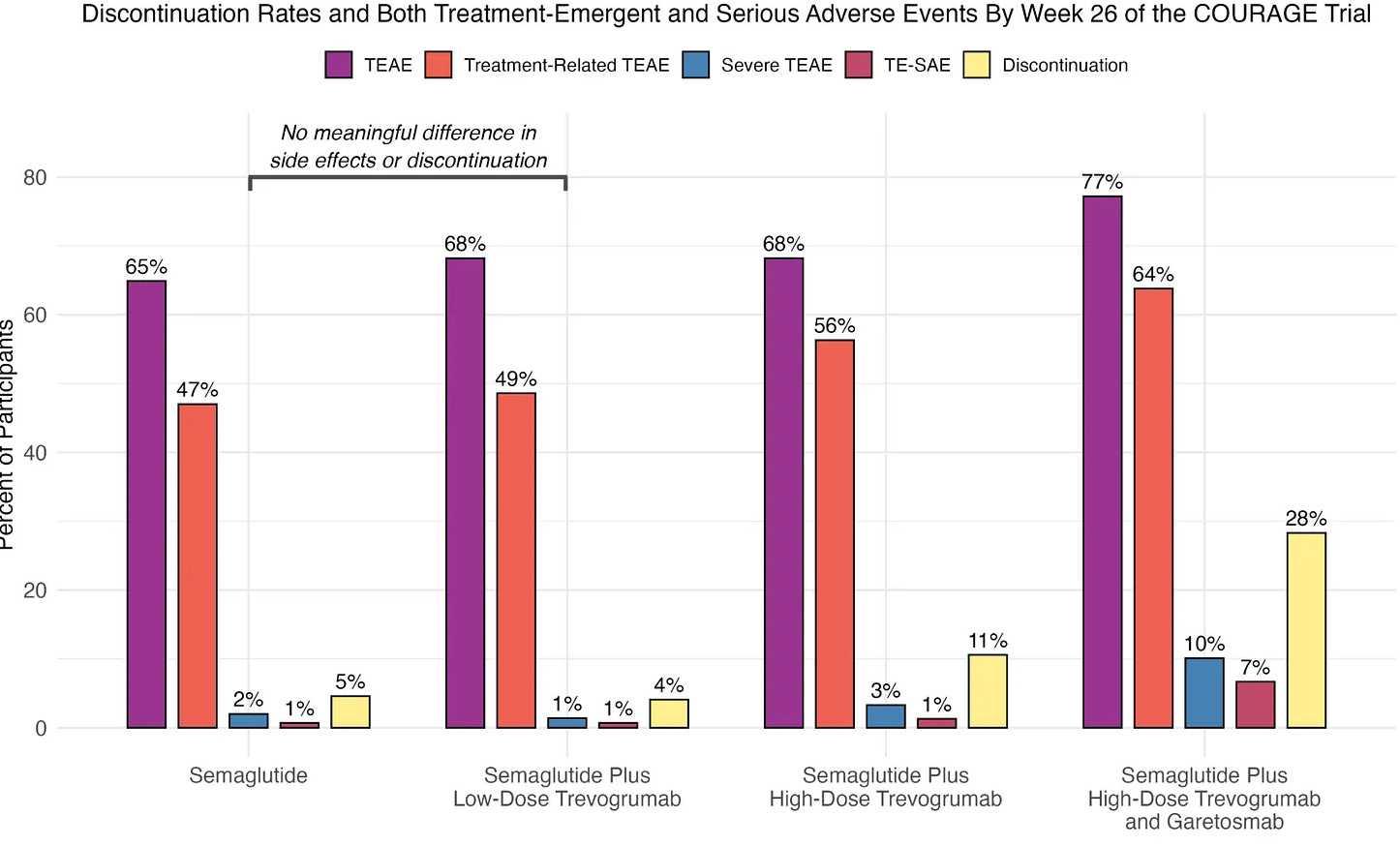

On the other hand, a triplet combination that added garetosmab showed even better results - preserving more muscle and burning more fat. However, more patients dropped out due to serious side effects, which would be a major problem for frail elderly patients who already have trouble tolerating medications.

This makes me think that the side effect profile with low doses seems reasonable, and we’ll get a clearer picture during in-depth readouts at the EASD conference in Vienna later this month.

Therefore, the realistic near-term comb looks like semaglutide plus low-dose trevogrumab delivered subcutaneously and titrated for potential Alzheimer’s patients.

The three possibilities

Base case: EVOKE shows a modest but convincing difference on CDR‑SB at two years with slowing of cognitive impairment in the range that we already accept from gold standard treatment.

In this world, Regeneron selects a trevogrumab dose that preserves about fifty percent of lean muscle mass loss and positions the combo for older patients with mild Alzheimer disease who are at risk of frailty.

Bear case: EVOKE shows no statistically significant difference on CDR-SB at two years and there is no Alzheimer’s label indication. The sarcopenia problem in older GLP-1 patients does not disappear, so Regeneron still has a use case but it’ll be outside neurodegenerative conditions.

Best case: EVOKE produces a stronger absolute gap and higher percent slowing on CDR‑SB, along with acceptable discontinuation rates.

In this world, Regeneron accelerates timelines and doses as oral sema becomes widely adopted in clinical practice.

Where we go from here

Whatever happens, the EVOKE trials are going to change how we think about metabolism and inflammation in neurodegenerative conditions.

If they work, we've found a new treatment pathway that doesn't require IV infusions or brain scans to monitor for swelling. If they fail, we'll know that GLP-1s aren't the metabolic answer to Alzheimer's - which saves billions in misdirected research!

But I'm betting they work. And when they do, everyone will focus on Novo’s success. However, we’ll know that Regeneron is the company that will make patients actually stay on treatment.

**The views, opinions, and recommendations expressed in this essay are solely my own and do not represent the views, policies, or positions of my employer or any other organization with which I am affiliated. This content is provided for informational purposes only and should not be considered medical, legal or investment advice.**

Fascinating, cheers Ash! Joining a dementia clinic tomorrow at Stanford 👀

I hope we find more answers in the future (near one) of Alzheimer’s research.