Why Novo Nordisk is Out of Options (Except One)

patents become weapons

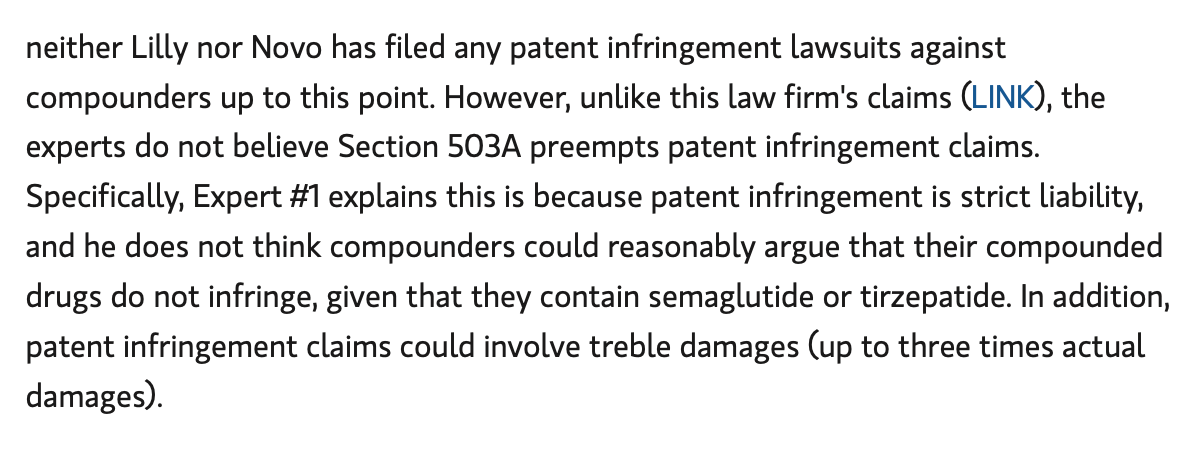

Ten days of silent meditation and the first thing the universe shows me is Novo Nordisk hemorrhaging $70B in market cap, the worst single day drop in in 40 years. The market gods, it seems, have quite the sense of humour. My one immediate thought was:

What in the hell did I miss?!

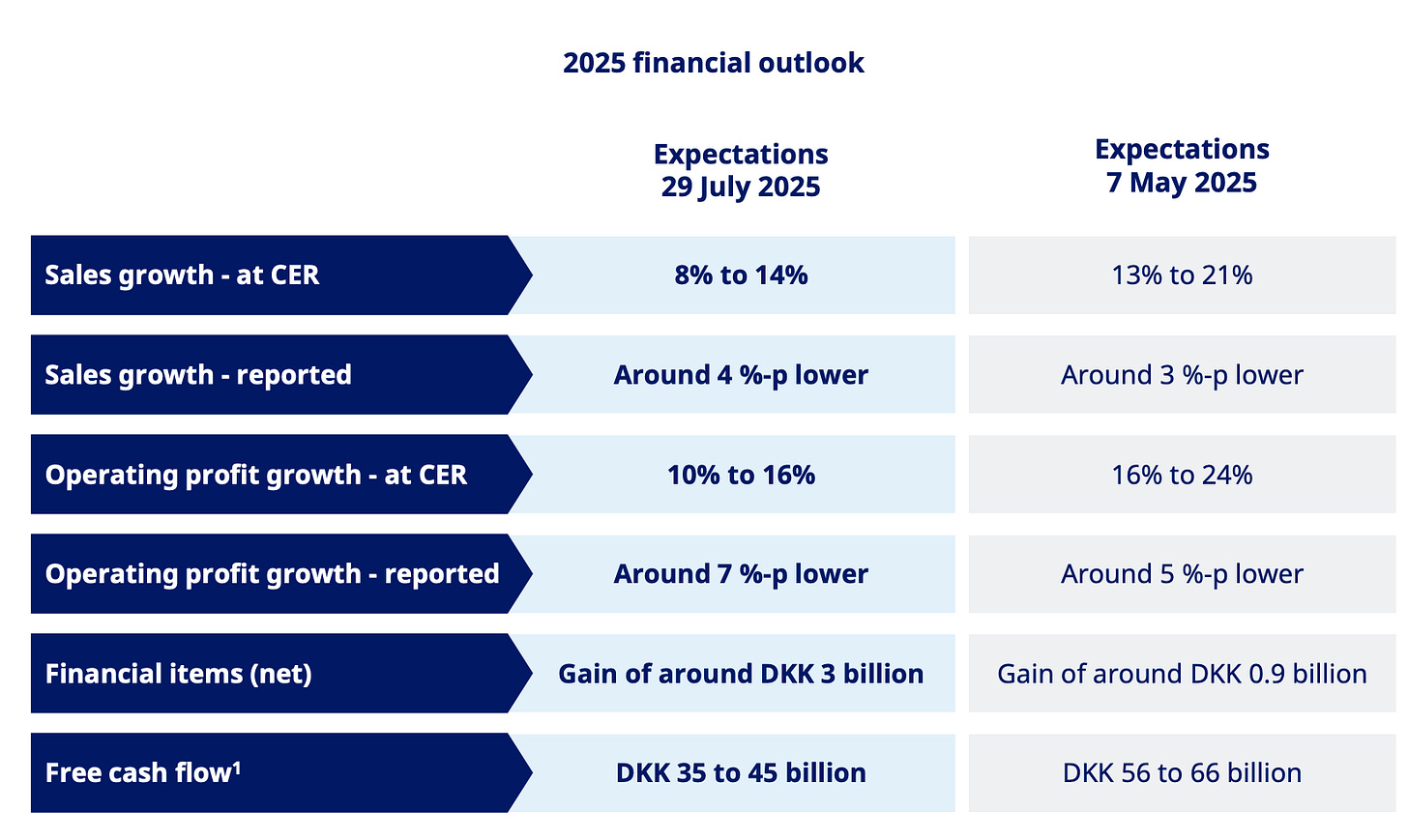

The answer, of course, was compounded semaglutide. Novo dropped its 2025 growth outlook from ~ 21 % to ~14% after Ozempic and Wegovy sales slowed in the US.

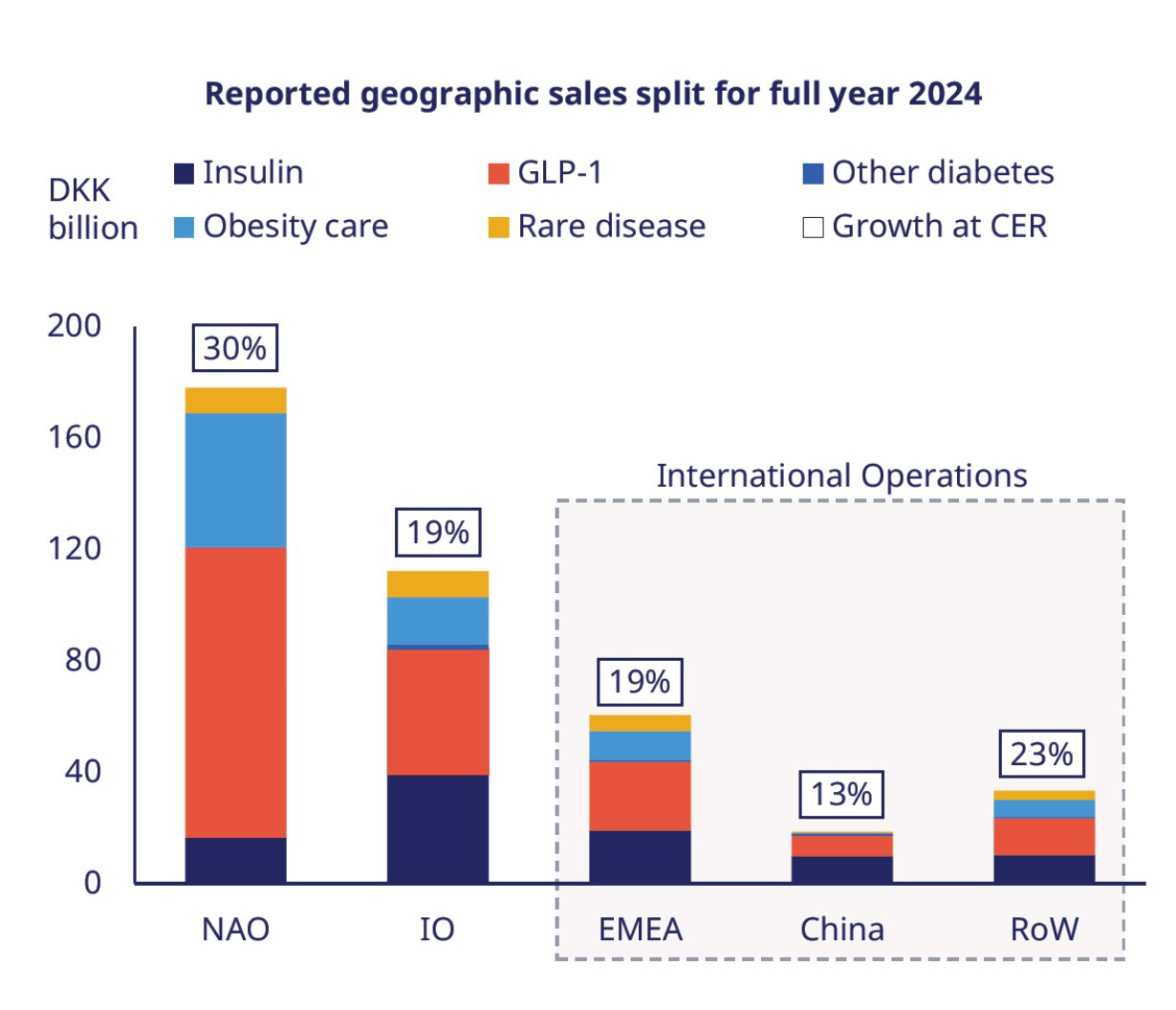

And since American GLP-1 sales are Novo’s primary cash generator, even a small ripple sends a mighty shockwave through the P&L.

According to the Outsourcing Facilities Association (OFA) data, 80 million compounded semaglutide prescriptions were dispensed in 2024. Logic would suggest these numbers would plummet once Novo Nordisk resolved their supply issues and the FDA officially ended the shortage designation.

But that's not what happened.

In their latest earnings call, Novo executives were vague about specific numbers but confirmed that compounded semaglutide was exceeding 1 million prescriptions.

Privately, every analyst I talk to thinks that number is multiples higher.

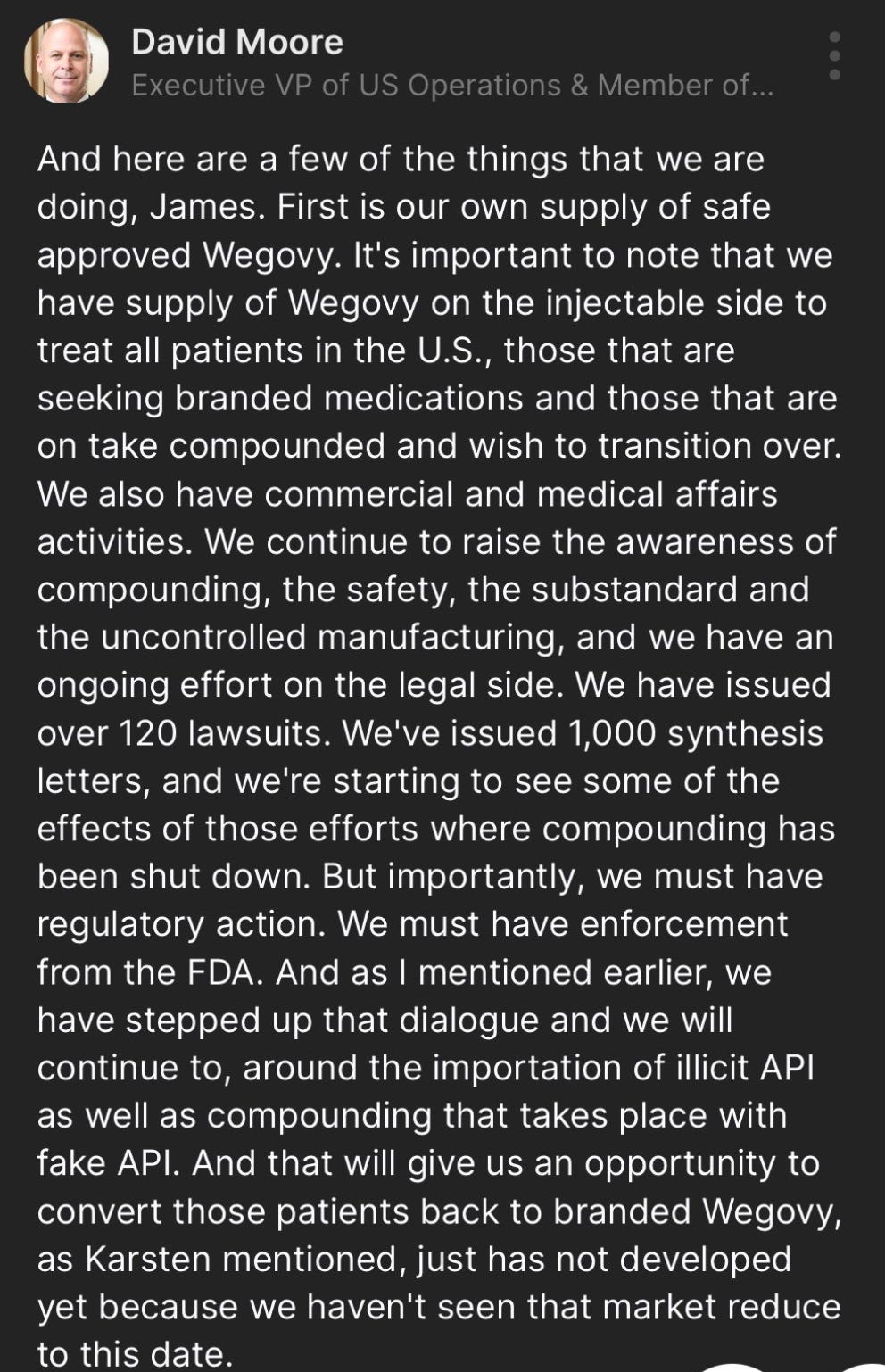

I also got the feeling there was wide-spread frustration and anger about the situation, but what made me raise my eyebrows was their apparent strategy of hoping the FDA would ride in and save the day by cracking down on Hims & Hers, and other compounders utilizing Section 503A of the FD&C act.

For a company of Novo's sophistication, betting on regulatory enforcement felt bizarrely passive.

And ultimately, I think this is a massive gamble.

Let me explain why.

The FDA Can't Save Novo (Even If It Wanted To)

The FDA's capacity for enforcement has been decimated. The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) just terminated roughly 3,500 FDA employees , which is about 20% of the agency's workforce. This includes:

Key staff responsible for inspecting compounding facilities

Laboratory teams who test imported API batches

Field investigators who track illegal supply chains

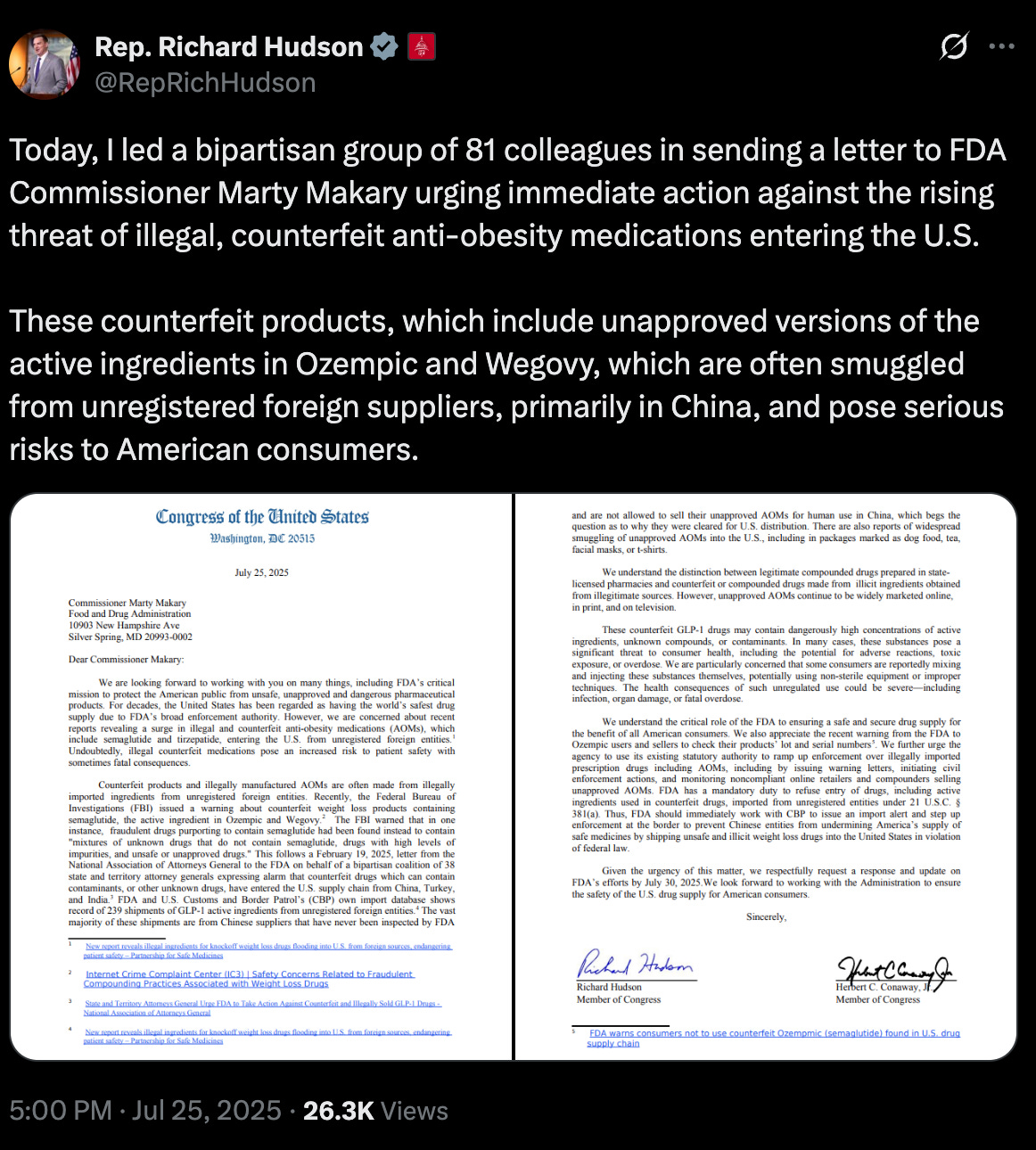

This makes the recent bipartisan push for FDA enforcement particularly ironic. Republican Senator Richard Hudson is leading efforts demanding the FDA crack down on ‘illegal’ semaglutide.

My immediate question is: How exactly?

Who’s left at the agency to enforce the rules if the labs are dark and the inspectors are quite literally gone?

But even beyond capacity constraints, the FDA faces a political nightmare. At $499 per month through NovoCare, Wegovy is well beyond what most Americans can stomach (pun not intended).

When wallets decide, safety slogans lose. Compounders ship “personalised” semaglutide for roughly $200, and consumers are voting with their wallets.

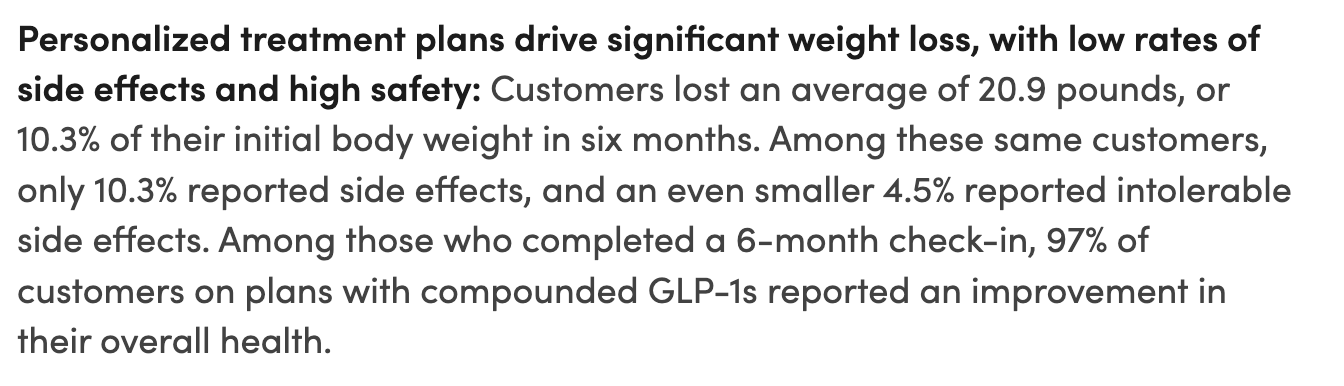

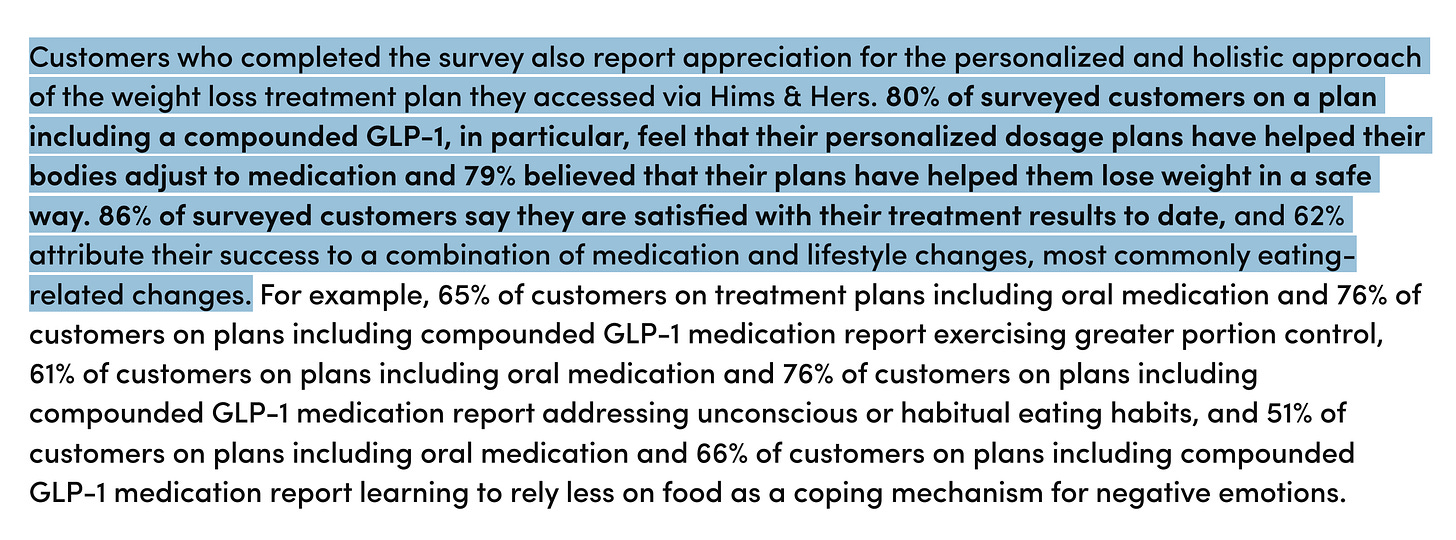

If the FDA swoops in now, headlines will scream Regulator Kills Cheaper Weight-Loss Drug. That’s a gift-wrapped talking point for every politician eager to bash Big Pharma (ahem, RFK). Hims & Hers has already primed the narrative by touting real-world data from 13,000 users that shows compounded semaglutide achieves the same-ish results as Wegovy (I don’t agree with the methodology, I’m just pointing it out).

Fair or not, the optics would be absolutely brutal.

As Dartmouth professor Jeffrey Parker explained in Bloomberg’s podcast Hims Won’t Let Go of Its Wonder Drug:

"This is a playbook straight from other unicorns like Uber and Airbnb—exploit regulatory grey areas to quickly build a loyal user base, then leverage those users to push back against regulation once it finally arrives."

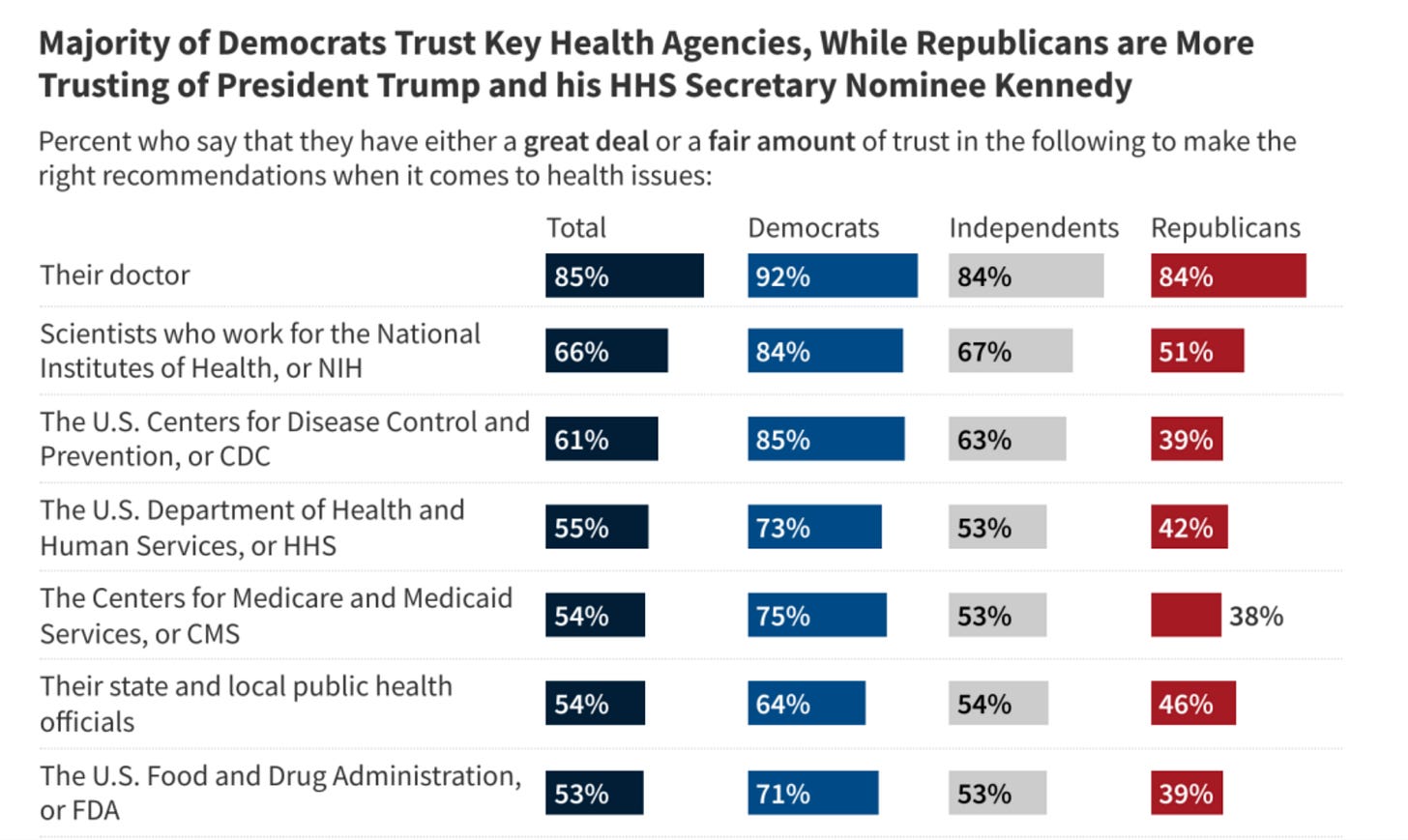

With public trust in the FDA already down 12 percent since 2023, the agency can ill afford another firestorm branding it as a guardian of pharma profits over patient access.

So if I’m right and the FDA doesn’t act, what happens to Novo’s GLP-1 pipeline if 503A compounding is allowed to continue?

The Compounding Playbook Will Cannibalize Novo's Pipeline

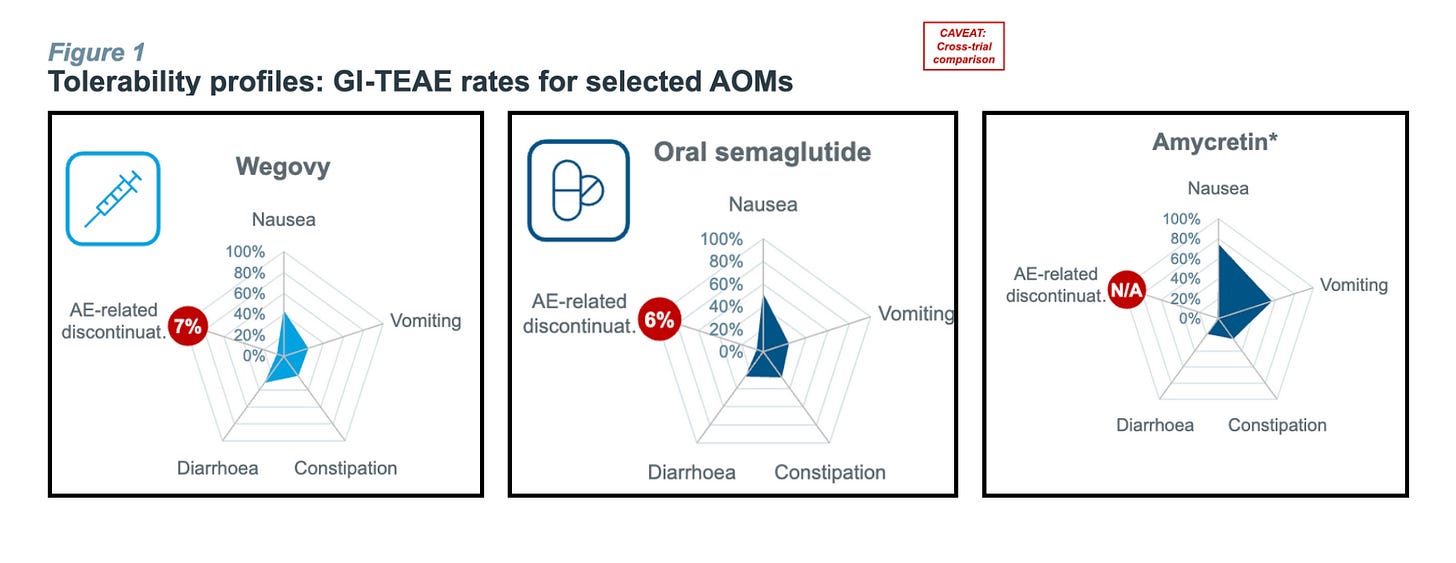

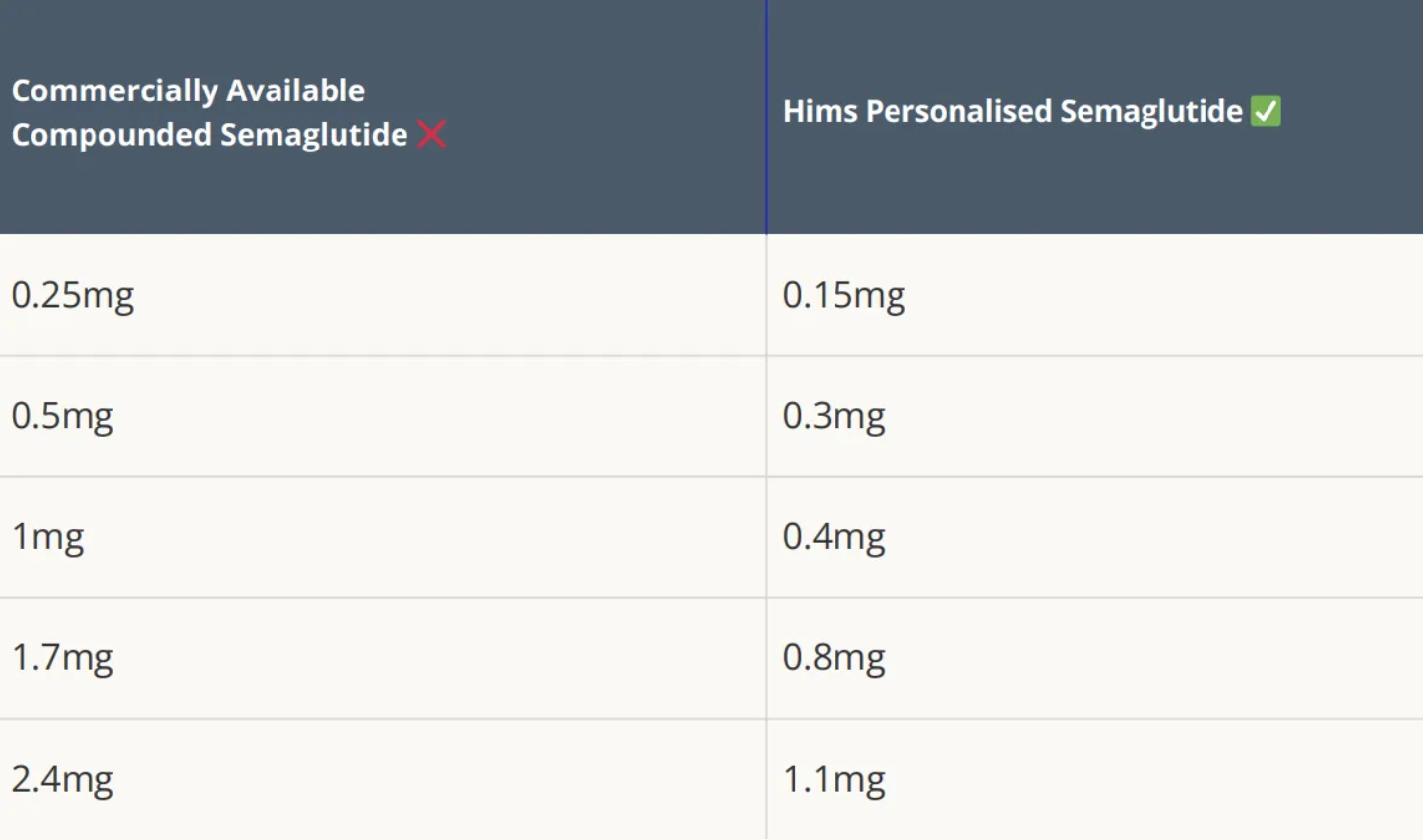

As I’ve written before, Hims have strategically interpreted section 503A of the FD&C act to their advantage by using common side effects encountered with semaglutide, such as nausea and vomiting, as justification for offering slightly tweaked dosages.

This small tweak transforms a commercially available drug into a "personalized" formulation, allowing Hims to scale production far beyond the intended regulatory limits.

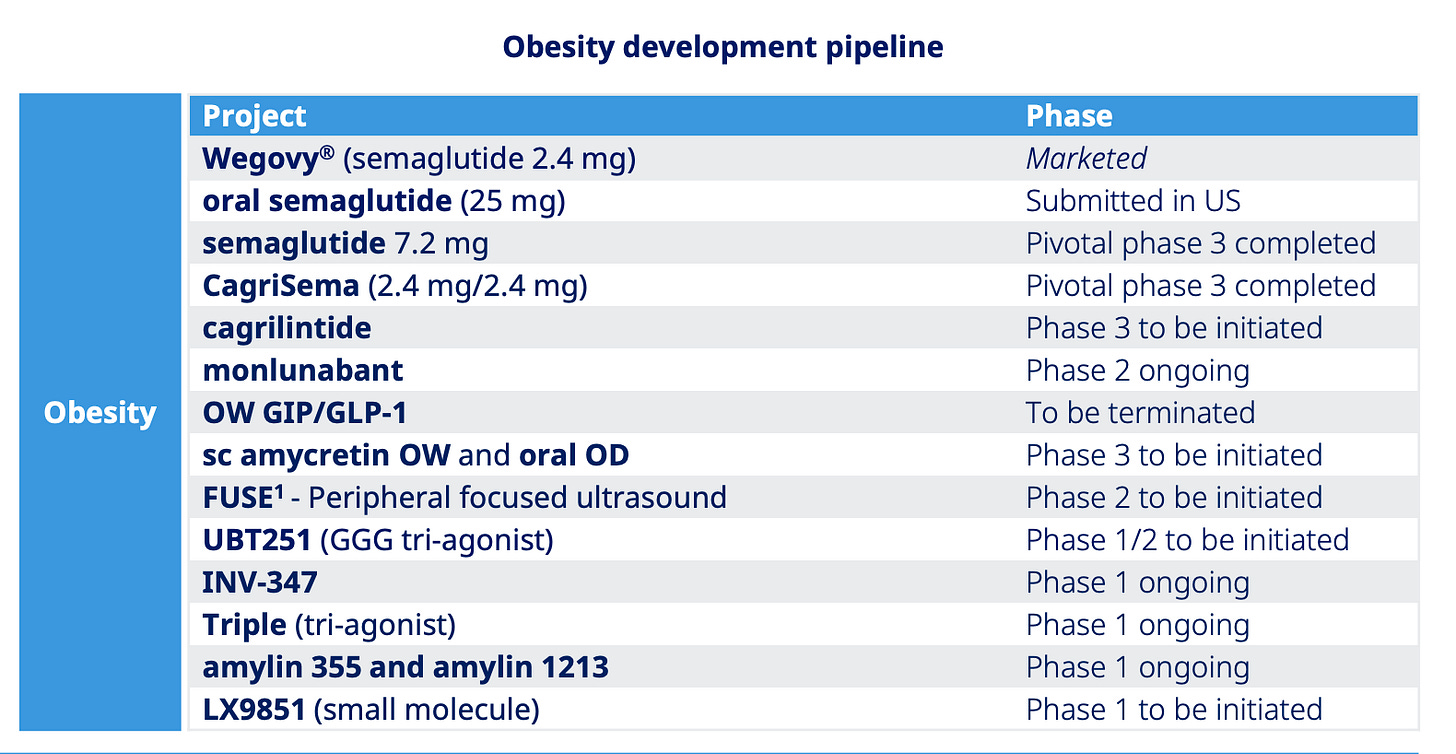

Now, apply this same logic to Novo’s upcoming GLP-1 meds.

What's stopping compounders from hijacking oral Wegovy (semaglutide) and CagriSema the moment they launch?

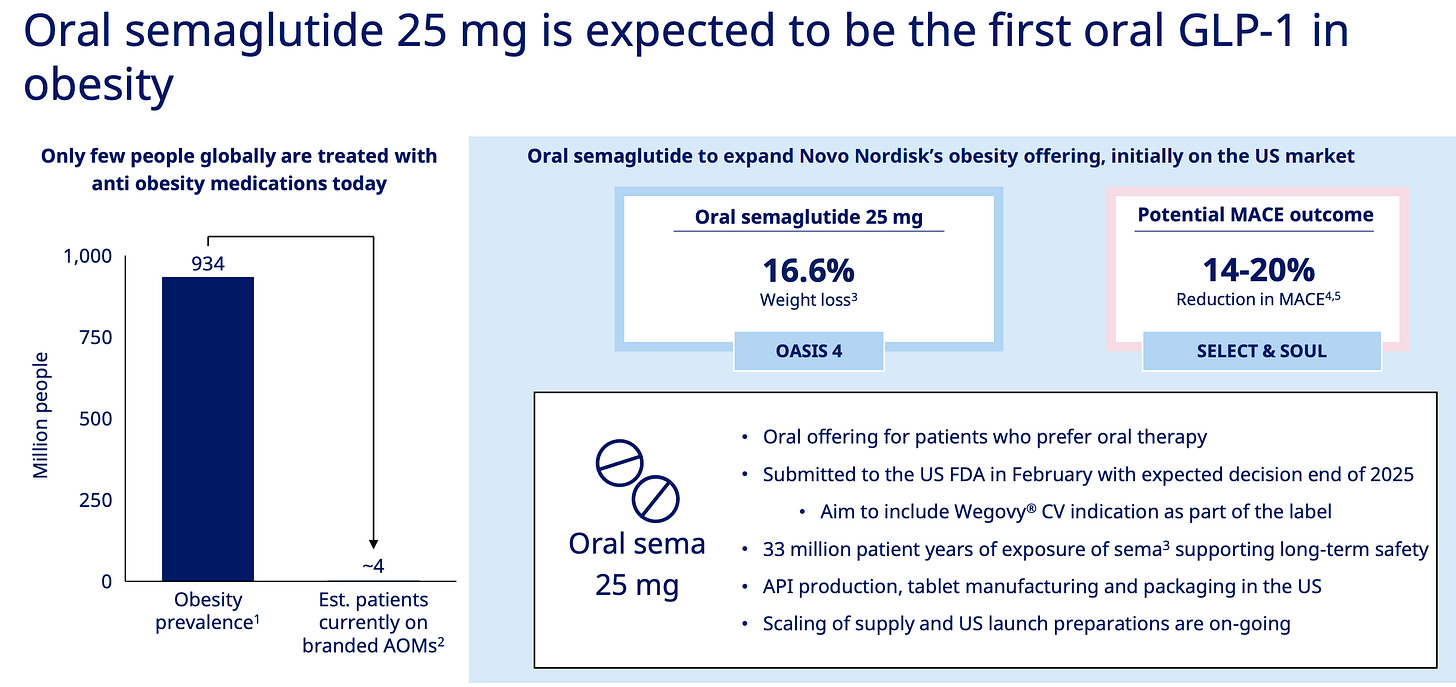

Let’s spotlight oral semaglutide for a moment. It’s launch in the US is expected in Q4 2025 and it’s essentially a higher-dose version of Rybelsus, a GLP-1 drug for type 2 diabetes that’s been on the market for years.

Like Rybelsus, it’s taken as a pill each morning on an empty stomach, and you must wait 30 minutes before eating or drinking- an inconvenience, not a deal breaker.

In return, oral semaglutide presents Novo with another opportunity to secure launching the first EVER oral GLP-1 medication specifically approved for obesity.

This is big news! and I’m excited by it.

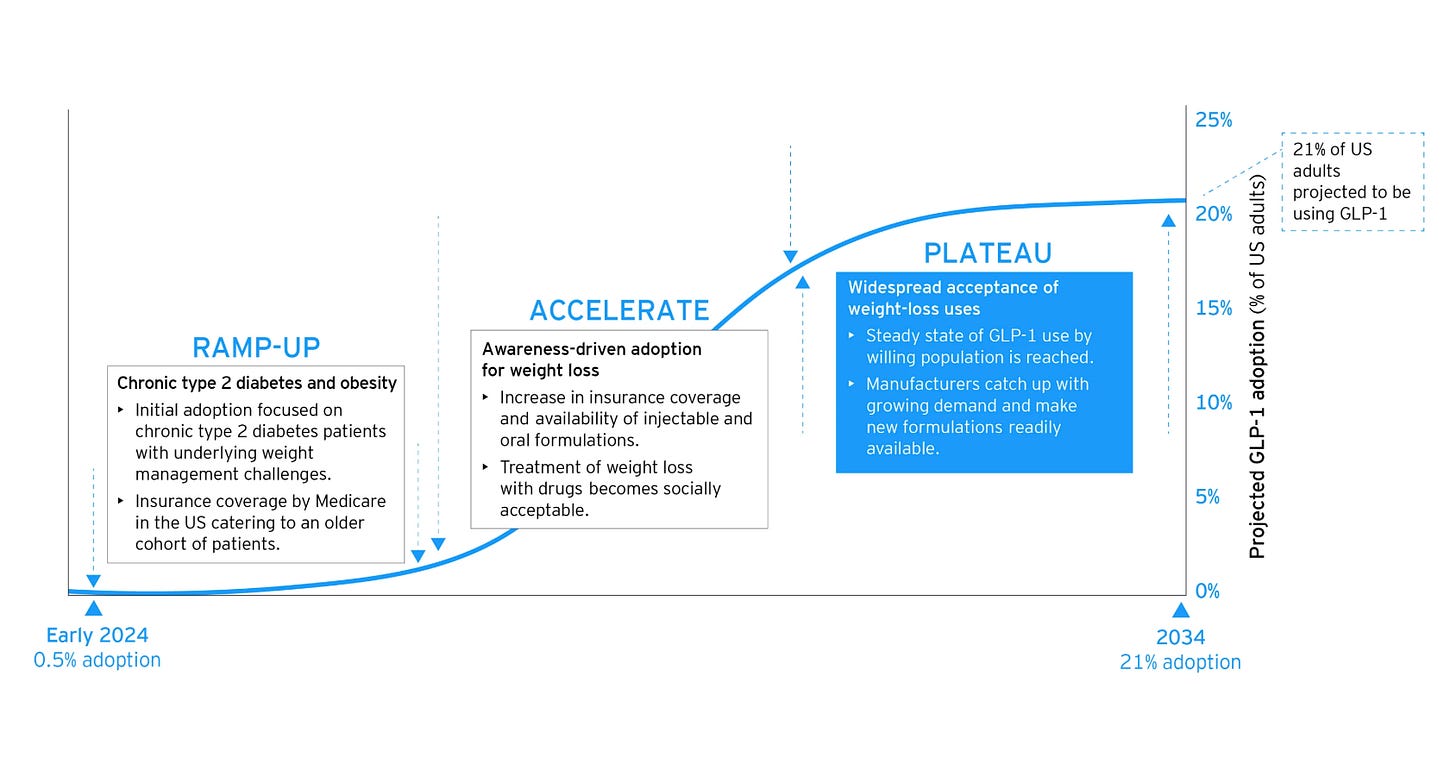

I think once oral versions hit the market, we'll see adoption accelerate dramatically. Like warp speed. The psychological barrier drops when you can take a weight loss pill just like a daily blood pressure medication. And most of all, no injections!

Within a year I suspect oral GLP-1s will become so ubiquitous that we'll forget there was ever a debate about their social acceptability. The conversation will shift from "Should people take these?" to "Which brand works best for you?"

But…Oral semaglutide carries a similar nausea, vomiting, and GI side-effect profile to Wegovy.

That “problem” is exactly the opening compounders love.

Hims can (and almost certainly will) argue that micro-dosing or custom titration “personalizes” therapy and improves tolerability, then pump out mass-scale pills under the 503A banner.

Or, they’ll compound the oral drug into a sublingual medication. All is within the realm of possibility that would undermine Novo's first-mover advantage and eat into their expected blockbuster revenues.

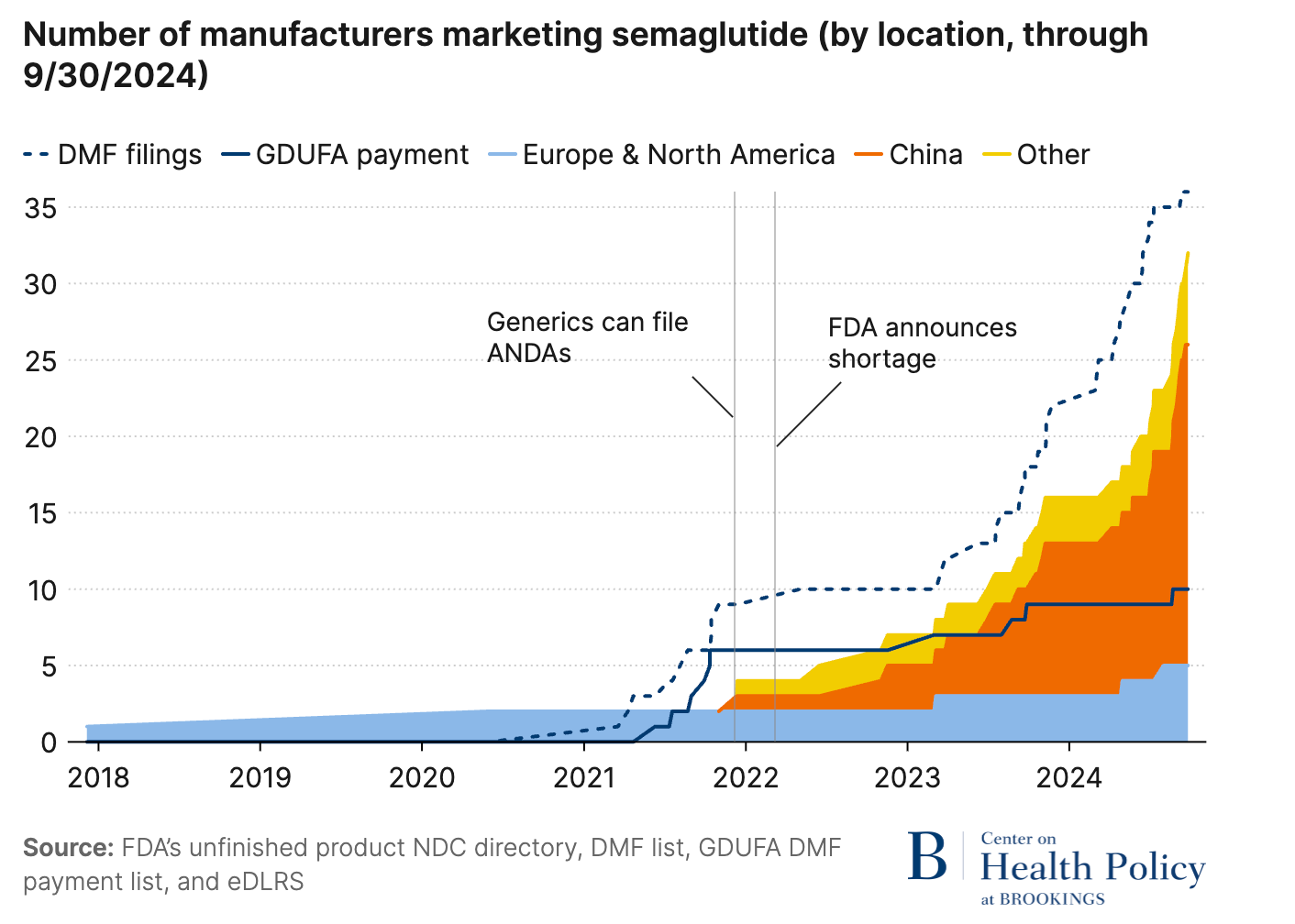

Skeptics might argue compounders can’t truly scale unless the branded drug first lands on the FDA’s shortage list. And only then do API exporters in China and India crank up production. (See the spike in Chinese semaglutide API exports the moment the 2024 shortage was declared.)

That defence falls flat on it’s face if Novo stock the shelves.

Oral sema’s convenience plus incoming Medicare/Medicaid coverage could very feasibly unleash demand from 70 million American patients within two years. Can Novo’s plants really smash out tablets fast enough to dodge another shortage label and the compounding free-for-all that follows?

If the answer is no, we rerun the entire 2024 saga. And betting on an understaffed, underfunded FDA to police it all is wishful thinking.

At this point Novo has two choices: keep bleeding market share and watch its multi-billion dollar pipeline go down the drain or swing the patent-litigation hammer.

The aggressive choice

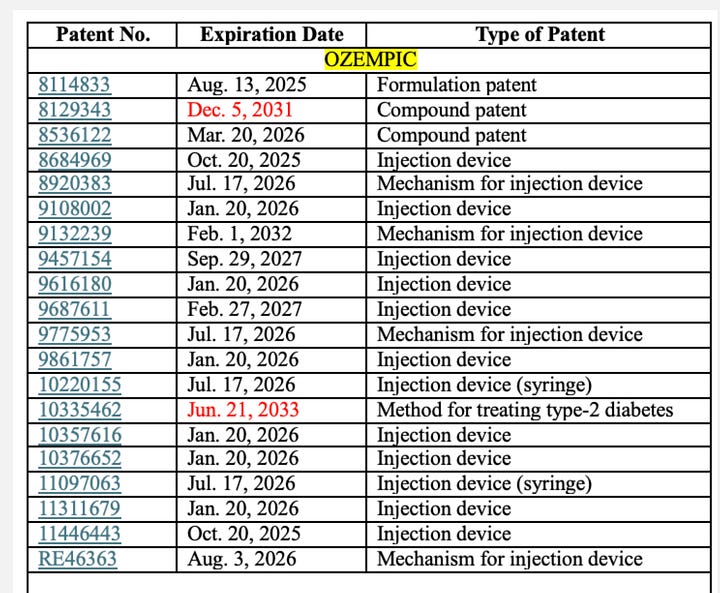

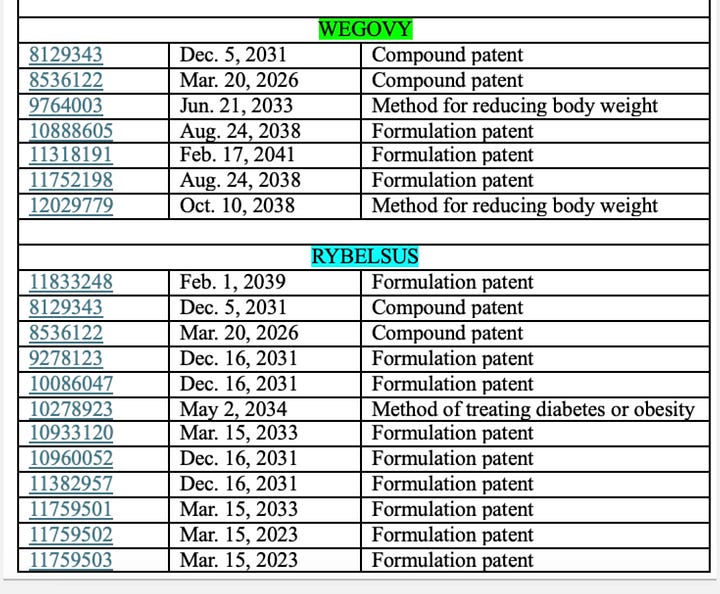

Patents are quite literally the backbone of pharmaceutical innovation. They grant inventors exclusive rights to manufacture and sell novel, useful drugs. For Ozempic and Wegovy, Novo holds multiple patents covering both the semaglutide molecule and the delivery devices.

Patent infringement occurs when another party uses, manufactures, sells, or imports a patented invention without explicit permission, triggering legal action aimed at enforcing patent rights.

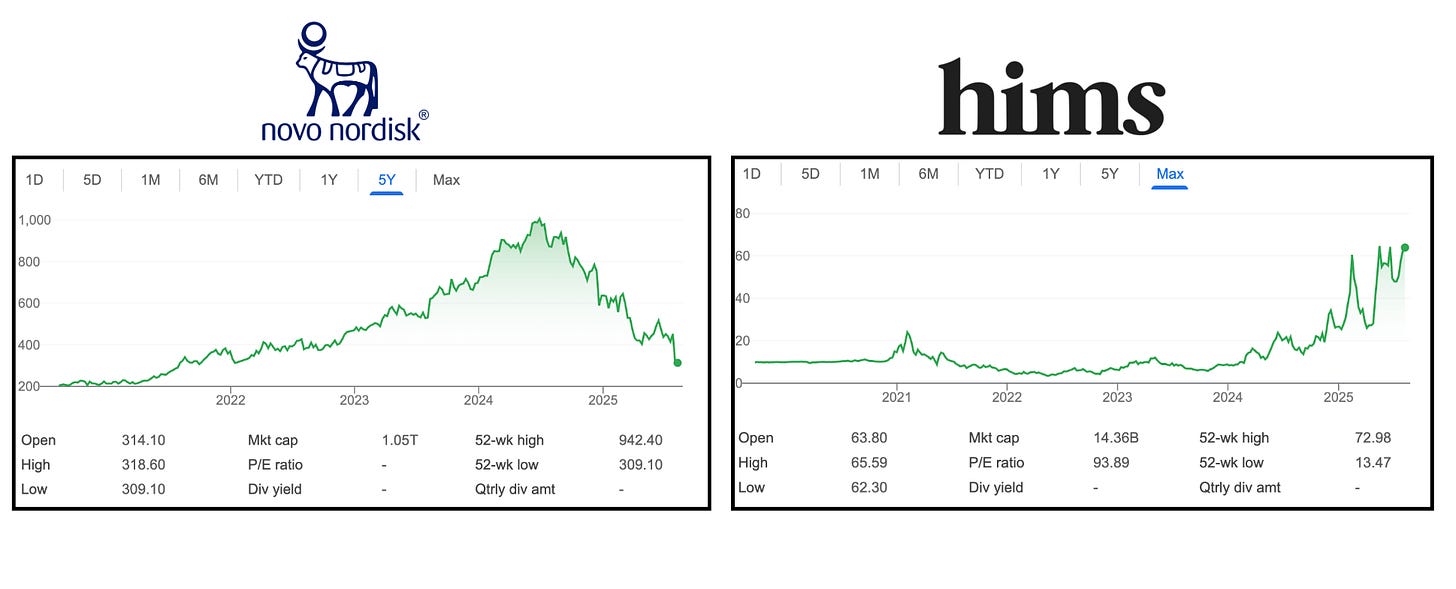

According to Morgan Stanley's discussions with IP lawyers, there's a critical legal case to be made that Section 503A compounding does NOT override patent infringement claims. More importantly, a 2024 law review from the Washington University School of Law stated that the FDA has no jurisdiction over patent law and no power to immunize compounding pharmacies from liability for patent infringement.

Essentially, patent litigation bypasses the inaction of the FDA entirely.

Patent infringement would also send an unequivocal message that Novo is serious, finally, about safeguarding its IP and revenue streams. Even the threat of IP infringement is enough to make the boldest of CEO’s run away and hide.

It would also spook HIMS investors and trigger massive stock price declines with radical behaviour changes in the industry.

So the question is, why hasn’t Novo pursued this yet?

Quite simply, there are “no examples of patent infringement lawsuits brought by drug manufacturers against compounding pharmacies that have reached trial or substantive judgments by courts.” And there is no guarantee that Novo would win.

It might also be true that Novo’s patents on Ozempic and Wegovy might be vulnerable to a counter claim and they could lose patent rights to Semaglutide.

What’s the alternative?

Is patent litigation like pressing the red button? Yes. It’s essentially a binary decision where you either lose, and you lose billions, or you win and you make the other guy pay billions.

A strategist friend likes to remind me that “war is a ladder”; you climb the lower rung with proxies first, and save your biggest, most destructive tool when you’ve exhausted every other option. Novo has already climbed:

PR “copycat” and “knock-off” soundbites to congress→ Barely dented telehealth sign-ups

Cease and desist letters→ Closed a few mum and dad pharmacies

Lanham Act lawsuits→ Hundreds filed but most end in big pharma losing or settlements that set no legal precedent.

FDA lobbying → $3 Million spent this year, 3,500 inspectors cut, Section 503A still unenforced.

Is the final rung worth it? Let’s see…

Will Hims & Hers simply choose to stop compounding voluntarily? Clearly, no. Compounding accounts for 30-40% of Hims' entire revenue and they're not walking away from billions voluntarily.

Could Novo drop their prices? Sure, but doing so would destroy the very economics that fund drug discovery. When a company invests decades into a molecule, the exclusivity window is its only shot at ROI. Erase that margin and the pipeline behind semaglutide, oral Sema, CagriSema, the next-gen GLP-1s never gets made.

Conclusion

Given the stakes, the risk of patent litigation are worth it. With oral semaglutide launching in Q4 and positioned to unlock a massive new market, the window for action is closing fast and Novo need to get a move on.

The question isn't whether they can afford to sue, it's whether they can afford not to.

**The views, opinions, and recommendations expressed in this essay are solely my own and do not represent the views, policies, or positions of my employer or any other organization with which I am affiliated. This content is provided for informational purposes only and should not be considered medical, legal or investment advice.**

Great article, thanks. I'd love to read your analysis of why Lilly seems to have been more successful stopping compounding of tirzepatide than Novo has been with sema. I've been curious about that.

Also it's worth noting that rhybelsus uses much more semaglutide per dose than the injectable, so that a small amount of that can survive the stomach. Also, the additional ingredients and processes to manufacture the semaglutide pills are much more complicated than the injections. This could make it harder for compounders to compete on price for pills, because their API cost and manufacturing complexity will go up.

I think GLP1s are unique and pharma companies cannot rely on the standard pricing model of charging a ton during the patent protected period. They are extremely easy to make - you can literally buy "next gen" GLP1s right now, it's completely legal as long as you don't inject it.

Instead I think they'll have to use more traditional tactics such as touting increased safety, price, availability, maybe even partnering with some competitor distributors. The market here is so incredibly huge I really believe there's plenty of profit to go around.

Compounders aside, there are, what, a dozen new GLP1s in trials? Even within the patented space there is going to be a ton of competition. Novo is still on the backfoot here, Cagrisema looks very promising but not as good as retatrutide