Why Novo Nordisk Won't Beat Eli Lilly

Dividends over R&D is not a good strategy

Hello and happy Sunday! Was this newsletter forwarded to you? Sign up to get it in your inbox.

Last weekend I attended an amazing wedding packed wall-to-wall with Americans from New York and California.

Somewhere between champagne toasts and great dance moves (mostly mine), we landed on Europe's supposed "lack of ambition." Honestly, I can't recall who started it. But knowing me, it was probably me.

My American friends were quick to point out that Europe was choking on regulation, suggesting all the exciting innovation these days is happening stateside. Okay, it’s getting harder to argue against that. Still, I found myself coming to Europe's defence.

But it got me thinking about this old, stubborn stereotype of European vs. American ambition. And it led me directly to a topic I've been mulling over: if we look at Novo and Lilly, two pharma giants from either side of this Atlantic divide, who's currently ahead, and what's actually driving their success?

This week is mostly a large dose of data and graphs. Let’s dive in.

🚨 Big Moves

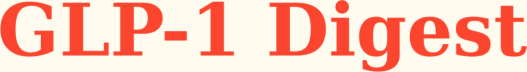

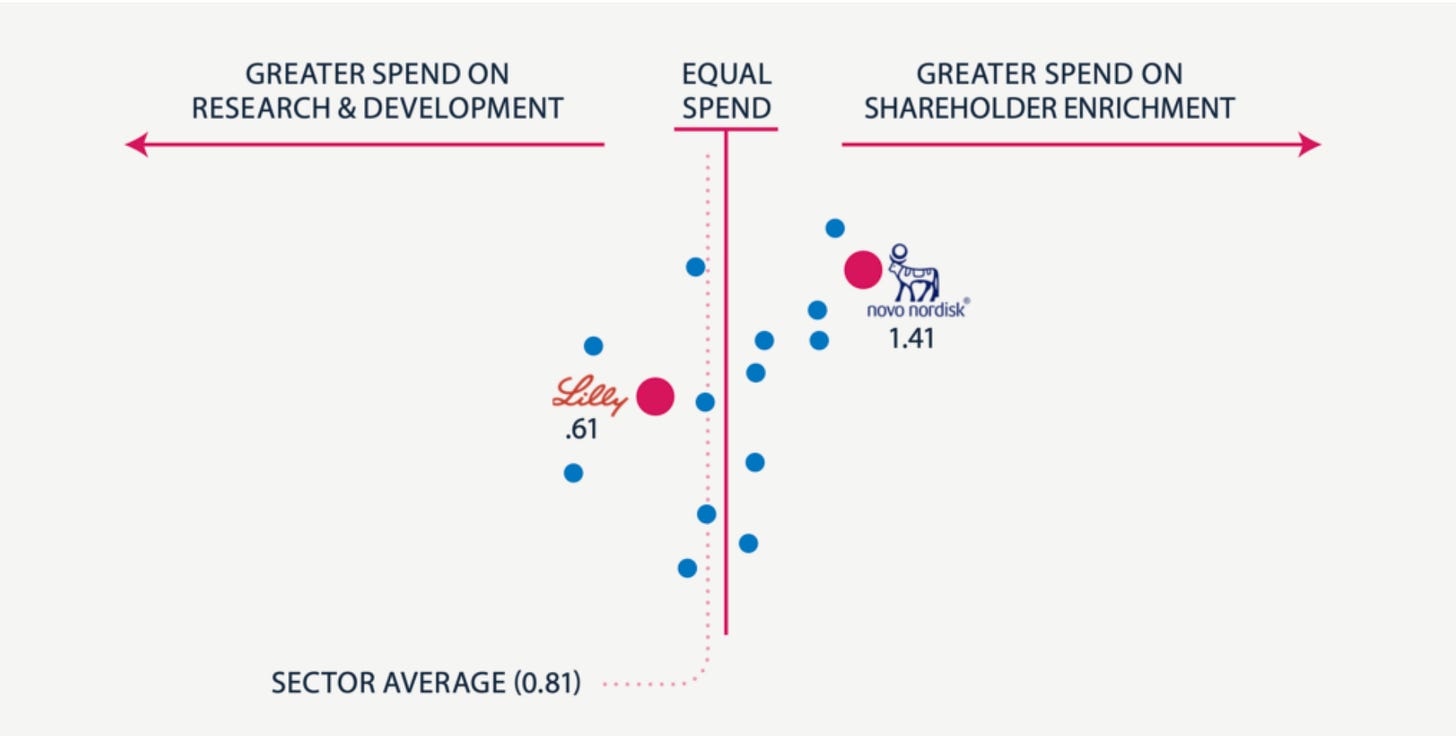

Novo Nordisk’s shareholder obsession is killing its innovation edge — Novo spends 40% more cash rewarding shareholders than building new drugs. Eli Lilly does the exact opposite and that's why Novo is getting crushed and why it’ll keep getting crushed.

Lilly's massive R&D spending has produced breakthrough therapies like retatrutide, showing fantastic prelim weight loss results, and orforglipron, an oral GLP-1 that patients can take anytime of the day without restrictions. Goldman Sachs projects orforglipron could capture significant share of oral treatments, a segment expected to explode to $22.3 billion by 2030 (24% of the obesity market) and $38.1 billion by 2035 (32%).

Instead of positioning itself for this massive opportunity, Novo's dividend-first strategy has produced a pipeline of disappointments: a 7.2mg sema injection, oral semaglutide which is basically Rybelsus at a higher dose hobbled by timing restrictions, and CagriSema that performs slightly better than Zepbound. I'm looking at this lineup and thinking - seriously? This is what you get when you prioritize dividend payments over R&D? these drugs are expensive iterations instead of market-exploding innovations and the stock market responded in kind.

Compare that to Lilly's approach. When your pipeline is rock solid, you can basically attack on all fronts. They’ve slashed Zepbound's price to just $399 per month, launched LillyDirect to sell medications directly to patients—cutting out pharmacy benefit managers and other healthcare middlemen—and triggered an intense price war across the industry.

And what does Novo do? They scramble to launch NovoCare months later, basically copying Lilly and hoping nobody notices.

Here's what I think is really happening here. Novo has fundamentally misunderstood what business they're in. They think they're a dividend stock that happens to make drugs, when they should be a drug company that happens to pay dividends. That's why they keep getting outmaneuvered by Lilly.

The fundamental question facing Novo is whether they actually want to win or simply remain participants in a $100 billion market. Their dividend-focused strategy suggests they have chosen the latter. Shareholders receive predictable returns while the company's competitive position steadily deteriorates.

This approach guarantees permanent second-class status, and nothing I’ve read suggests they'll change course.

📊 Inside the Numbers

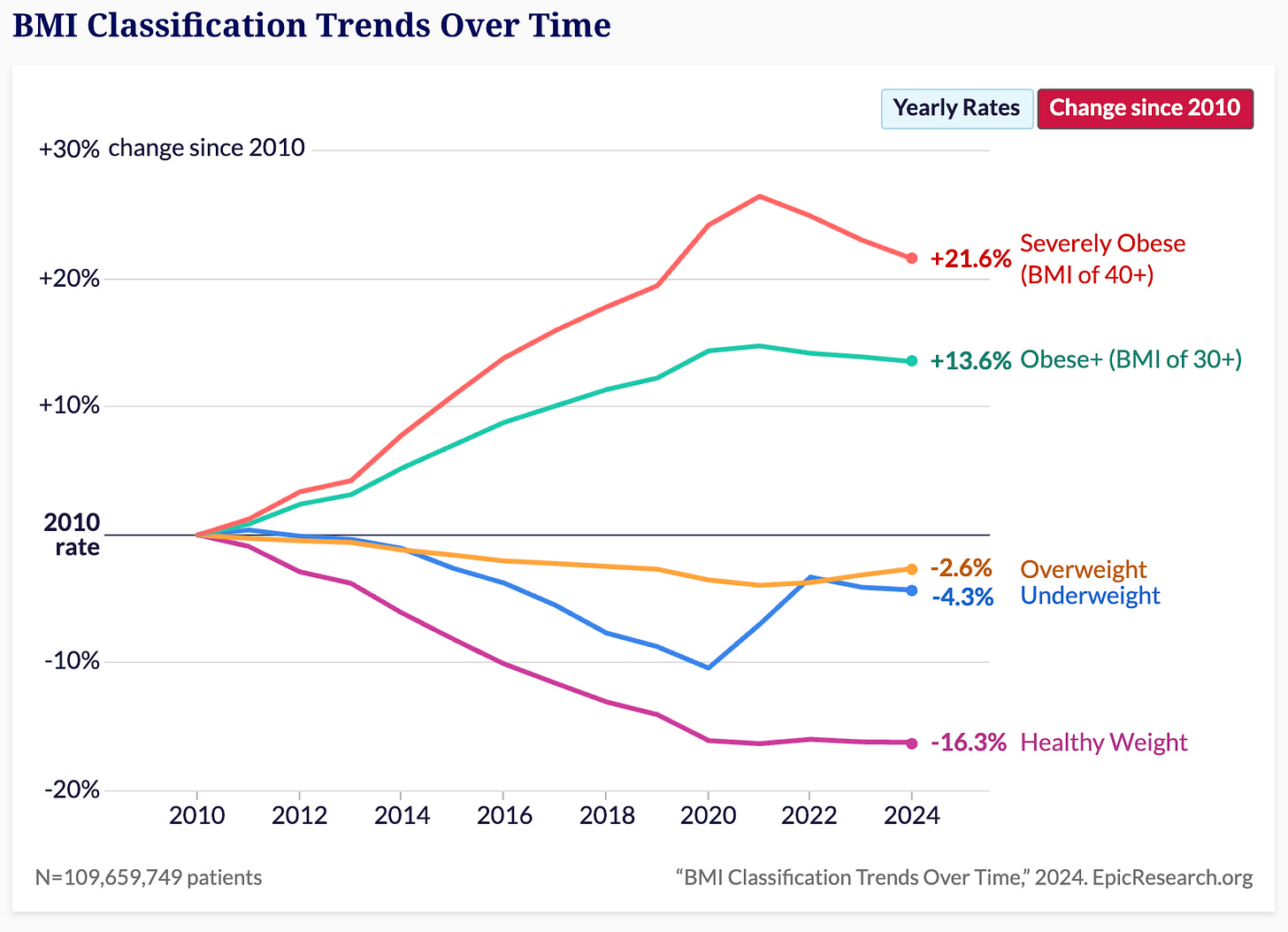

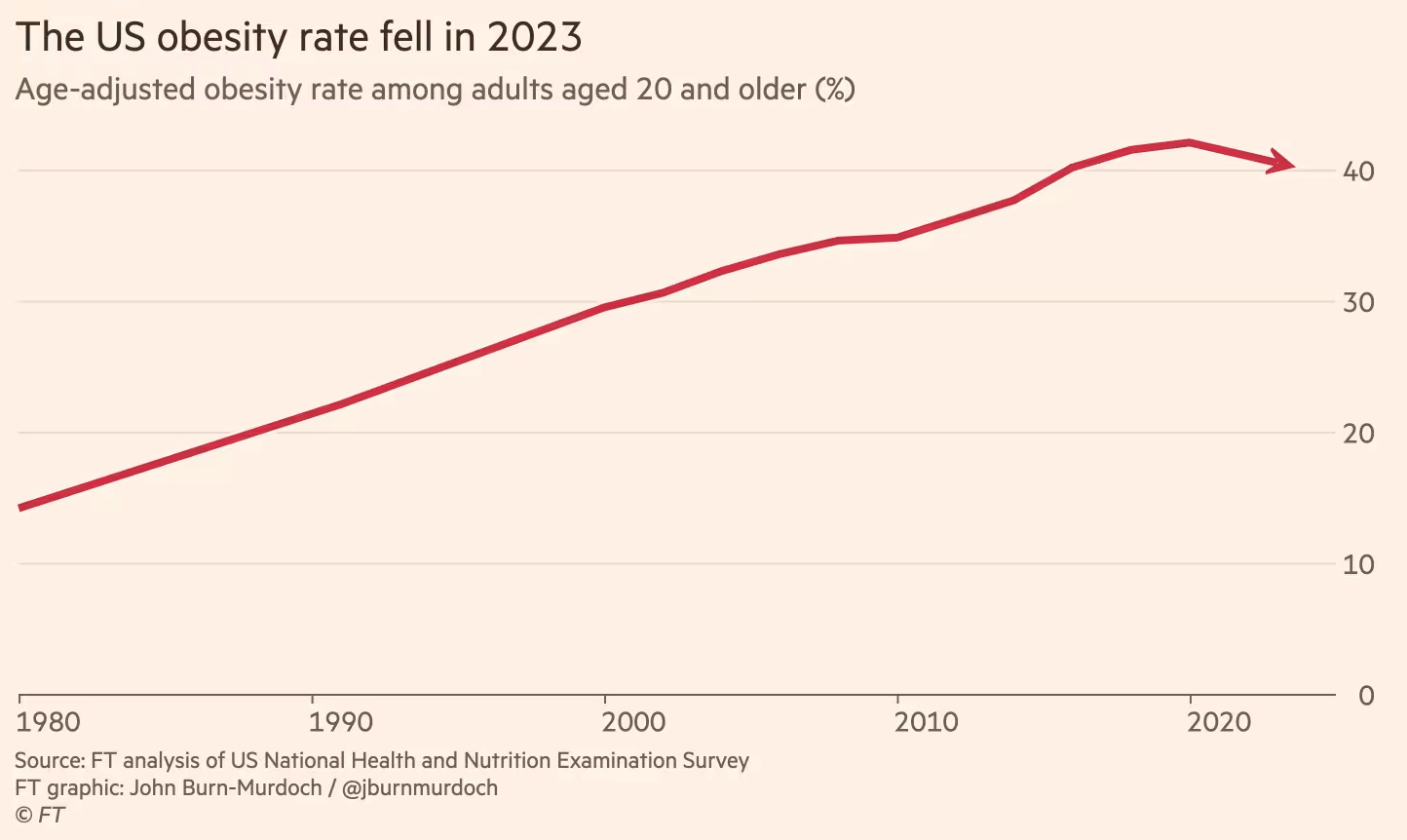

Two separate studies have captured something extraordinary happening to America's obesity rate — Epic Research analyzed BMI data from over 109 million outpatient clinic visits between 2010 and 2024. They found obesity rates climbing steadily until 2020, and then…stabilizing. Even more interesting was that severe obesity (BMI 40+) peaked in 2021 and has now actually started declining.

Last year, the Financial Times, using national health survey data, found overall obesity rates dropping two percentage points from 2020 to 2023.

The timing lines up almost too perfectly. What's behind the reversal? GLP-1s? Well, they are everywhere.

Roughly one in eight Americans now uses these medications, an astonishing surge in just a few short years. Yes, we can't absolutely, unequivocally prove these drugs single-handedly flipped the obesity curve. But given the unmistakable correlation, you'd have to perform some Olympic-level mental gymnastics to think they're not playing a starring role here.

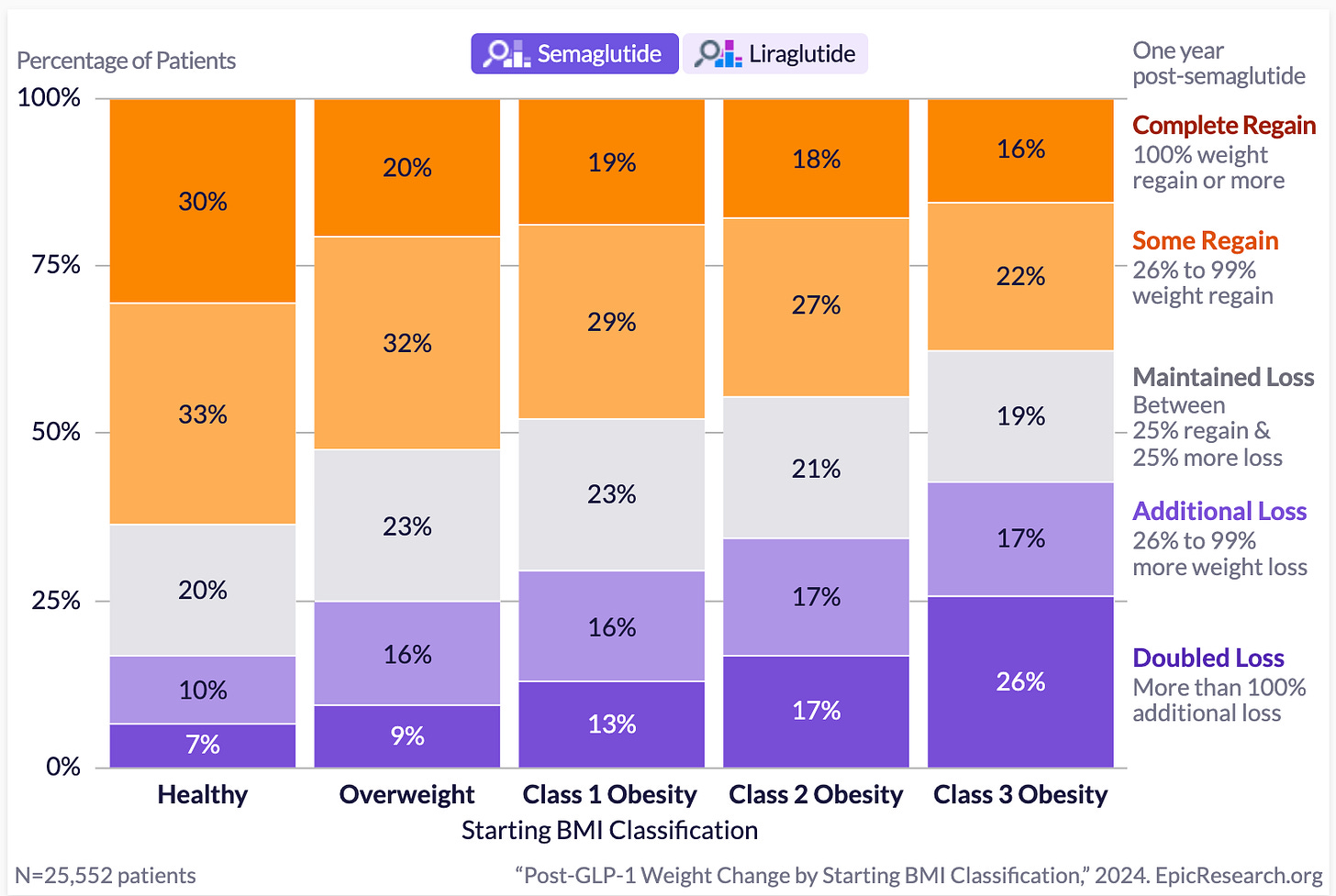

What happens when patients stop taking GLP-1s? — Another Epic Research study (you should follow them) analyzing over 59,000 patients prescribed semaglutide or liraglutide between 2017 and 2023 provides the clearest evidence yet about who maintains weight loss after stopping GLP-1 treatments—and why.

Researchers tracked patient outcomes for a full year after discontinuing medication, using prescription end dates or calculated refill schedules to determine exactly when each patient stopped treatment.

The study showed three key insights:

Semaglutide’s biggest long-term impact is in severely obese patients. This graph below shows how patients’ weights changed one year after stopping semaglutide treatment, categorised by their initial BMI.

For patients starting with severe obesity (Class 3, BMI ≥40):

26% more than doubled their initial weight loss even after treatment stopped

17% lost additional weight

19% maintained their weight loss, keeping their weight stable

Altogether, this means nearly two-thirds (62%) of severely obese patients successfully maintained or improved their results even after discontinuing semaglutide.

This genuinely surprises me, and it should surprise you too. I expected these numbers to be much worse based on what we've been hearing from the recent Oxford meta-analysis, which showed patients typically regain weight at a rate of about 0.8kg per month after discontinuing GLP-1 medications.

Why such a stark difference between these two findings? I could guess: maybe real-world conditions differ significantly from clinical trial settings; maybe these patients have strong motivation or better support networks; maybe there are lasting metabolic or behavioural changes triggered by significant initial weight loss.

But if I'm honest, I don’t know. It’s probably a combination of lot’s of different factors. GLP-1s could have powerful, lasting effects in certain groups—but precisely why remains anyones guess.

For those of you who are eagle eyed, you would’ve noticed that for patients who started at a healthy weight:

Only 7% doubled their weight loss

10% achieved additional weight loss

20% maintained their weight loss

This means that overall, just 37% of healthy-weight patients maintained or improved their weight loss long-term, while the majority (63%) regained substantial amounts of the weight they lost.

Here's what I think is happening. Many of these healthy-weight patients probably got semaglutide for diabetes, not weight loss. For diabetic patients, weight-loss goals are secondary, and their weight-loss results typically smaller.

As a result, their long-term outcomes may appear weaker compared to severely obese, non-diabetic patients whose goal was substantial weight loss.

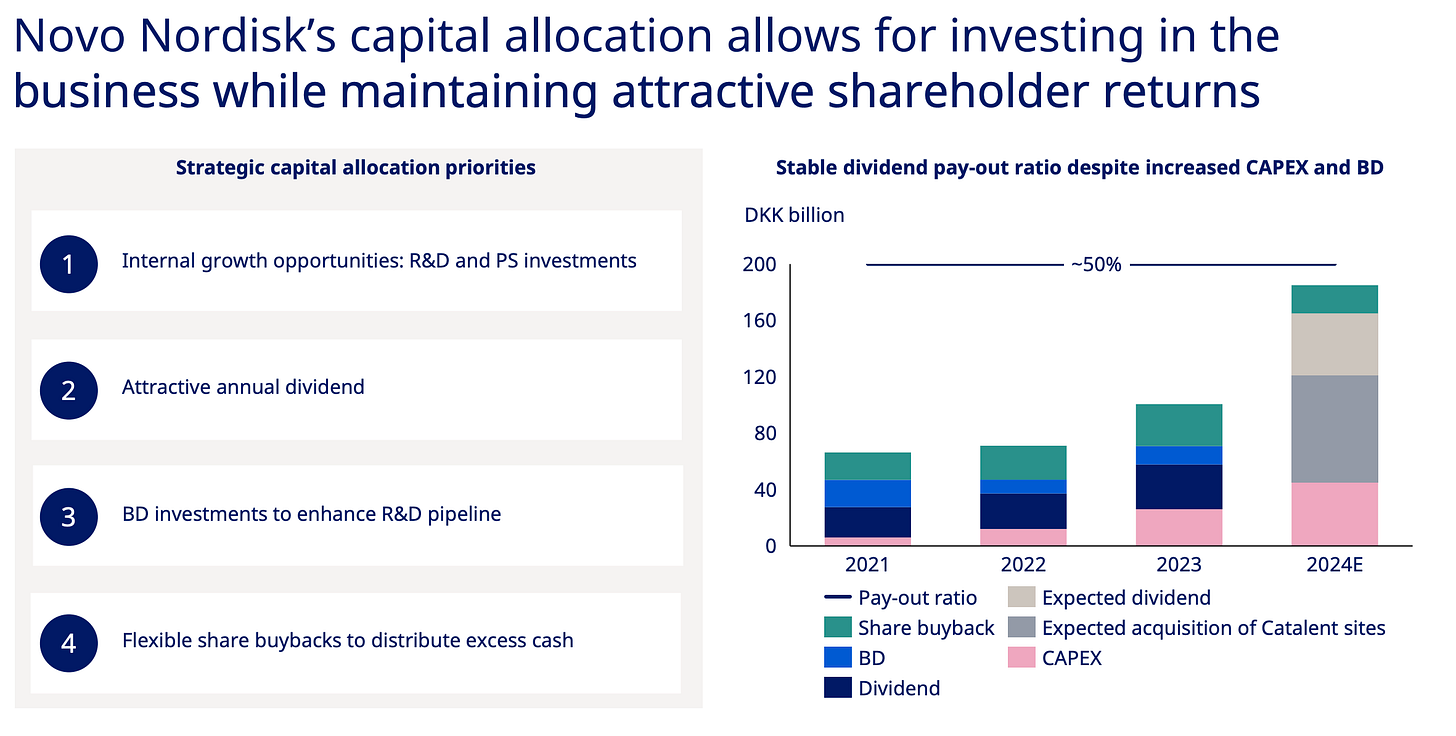

Early weight loss predicts long-term success after semaglutide

Patients who lost the most weight early on (over 40 pounds) had dramatically better outcomes after stopping treatment:

38% successfully maintained their weight loss

20% lost even more weight

9% doubled their initial weight loss

Together, this means that about two-thirds (67%) of those who lost at least 40 pounds initially maintained or improved their outcomes even after discontinuing semaglutide.

In direct contrast, patients who initially lost less weight (5-9 pounds) had notably worse long-term results:

27% completely regained their weight.

19% regained most of it.

Only 25% doubled their initial weight loss.

What’s going on here?

It might be due to the fact that patients who achieve significant early weight loss enter a sort-of positive feedback loop where they notice improvements in health and this motivates them to be healthier which propels weight loss even after meds finish.

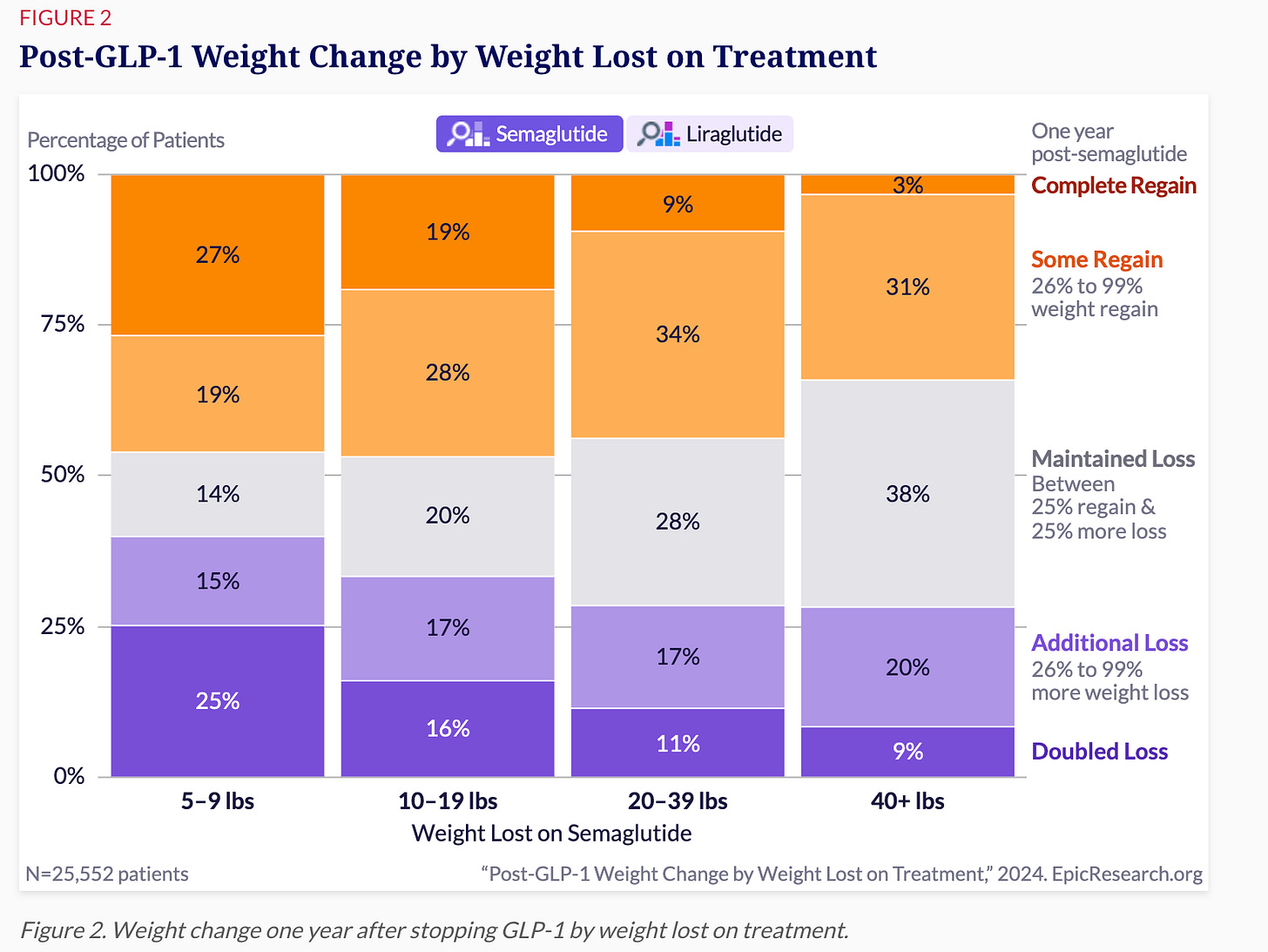

Longer treatment duration helps.

Patients who stayed on GLP-1 medications for a full year or more had better results after stopping. Nearly 60% of these patients successfully maintained or continued their weight loss, compared to lower success rates among those who used the medications for shorter periods.Again, I don’t fully understand why longer treatment leads to sustained weight loss. It might be behavioral change, metabolic shifts, or something else entirely. The data clearly shows that longer treatment works better long-term—but I’m going to remain slightly cautious about stating why.

*The views, opinions, and recommendations expressed in this essay are solely my own and do not represent the views, policies, or positions of my employer or any other organization with which I am affiliated. This content is provided for informational purposes only and should not be considered medical, legal or investment advice.*