The 5 most important ideas for 2026

Seismic shifts are underway in the GLP-1 market

I started writing this newsletter about eight months ago while suffering from a serious case of ‘man flu’ and needing a distraction from the void that opens when you’ve watched Lord of The Rings: The Return of the King (extended edition) for the 17th time.

I could’ve never imagined the lift-off it’s taken since, and I’m so genuinely grateful you’re here reading my words.

And since you are, my aim with each issue has been the same: you should finish every piece feeling smarter than you did before.

To do that, I’ve pushed myself to read what most people skip, like the footnotes in earnings calls (very handy) or the data buried in clinical trial material (very, very handy). What I find shapes what I write, and that can sometimes be a weekly digest on the news, or a much deeper piece that challenges the status quo, like why did the market overreact to orforglipron? Or what happens to life insurance when GLP-1 patients look healthy on paper but quit after a year?

Although getting each essay just right sometimes feels like I’m pulling my own teeth, I’ve loved every second of it and I hope you’ve found it useful.

As a thank you, I’ve put together some of the most important ideas I’m following for next year.

Let’s get into it.

D2C IS EATING HEALTHCARE

1. Whoops, we built a screening program

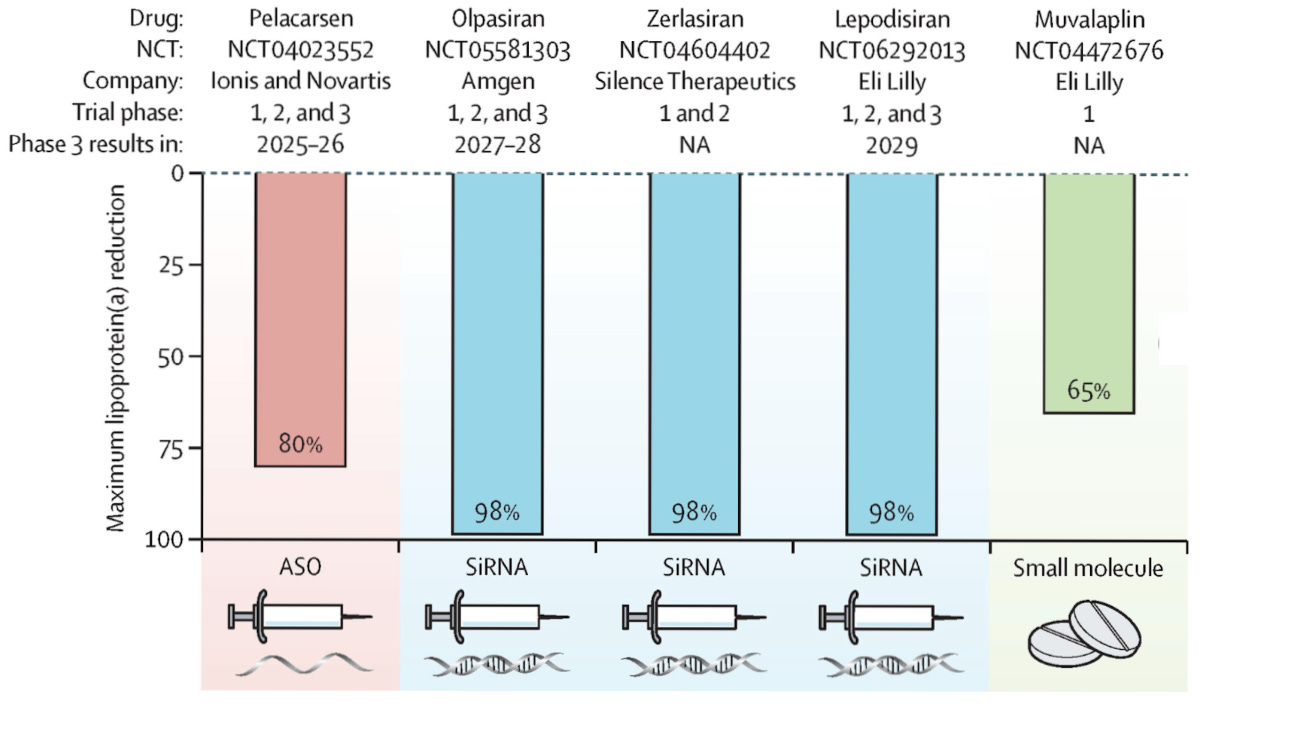

Since I have a family history of aunts dying young, I recently decided to get my Lp(a) tested (nothing like all-clear health reports to get you prepped for some holiday feasting). What surprised and annoyed me was how bloody difficult it was — I couldn’t find a single private provider in the UK offering it as an add-on panel, and going through the NHS would mean a 6-12 week wait, assuming my GP agreed to order the test at all, or even knew what it was for.

I assumed I was missing something.

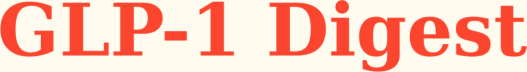

Surely people were getting tested somewhere! While the UK doesn’t seem to track this kind of data, the US does. A study published two months ago in JACC documented every Lp(a) test ordered through the US healthcare system between 2015 and 2024. At first glance, I thought the numbers were impressive. A jagged line pointing upward, oooh.

Indeed, there’s been a 22x increase in testing in just under a decade. But even after that surge, you’ve only screened ~0.2% of the US population.

For context, Lp(a) is a particle made by the liver that carries cholesterol through the bloodstream. Unlike the standard cholesterol your doctor might test for, Lp(a) levels are roughly 97% genetic, meaning diet and exercise won’t budge it, and neither will statins nor any other FDA-approved, licensed treatments on the market (off-label options are PCKS-9i’s).

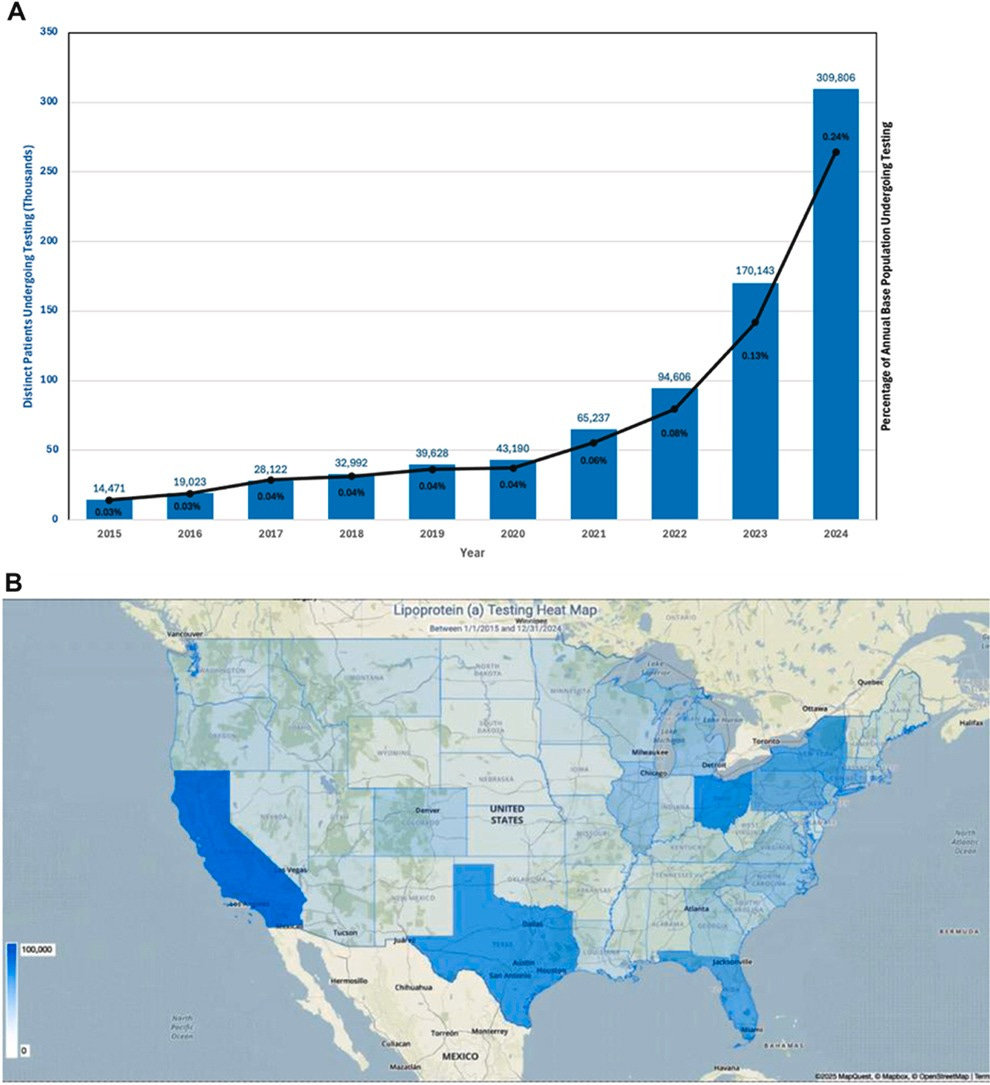

What makes this particularly irksome is that we know from hundreds of thousands of patients and genetic studies that elevated Lp(a) levels are an independent and causal risk factor for cardiovascular disease, aortic valve stenosis, and death among men and women across ethnic groups.

Unfortunately, one in five people carries these high-risk levels, translating to roughly 60 million Americans and 14 million Brits walking around with a potent cardiovascular risk factor they’ve probably never heard of.

So why isn’t the healthcare system screening for this? The short answer from a US perspective is that insurance rarely covers it, and many physicians won’t order a test if they don’t think they can do anything about the result. Both objections, however, are moot as all three major cardiovascular societies, including the European Atherosclerosis Society, the Canadian Cardiovascular Society, and the National Lipid Association, recommend at least once-in-a-lifetime testing for all adults (with or without cardiovascular disease).

But while the healthcare system drags its feet in making the test available, D2C has sprinted ahead.

Function Health has roughly 250,000 members, and Lp(a) testing is included once in its annual membership; that’s 250,000 single Lp(a) tests conducted in about 3 years!

That means a D2C company is approaching the testing volume of the entire US healthcare system. If you zoom out and add the other large blood testing providers like Superpower and Quest (D2C arm), which hardcode Lp(a) into their baseline panel, my view is that these companies are building America’s largest cardiovascular screening program without actually realizing it.

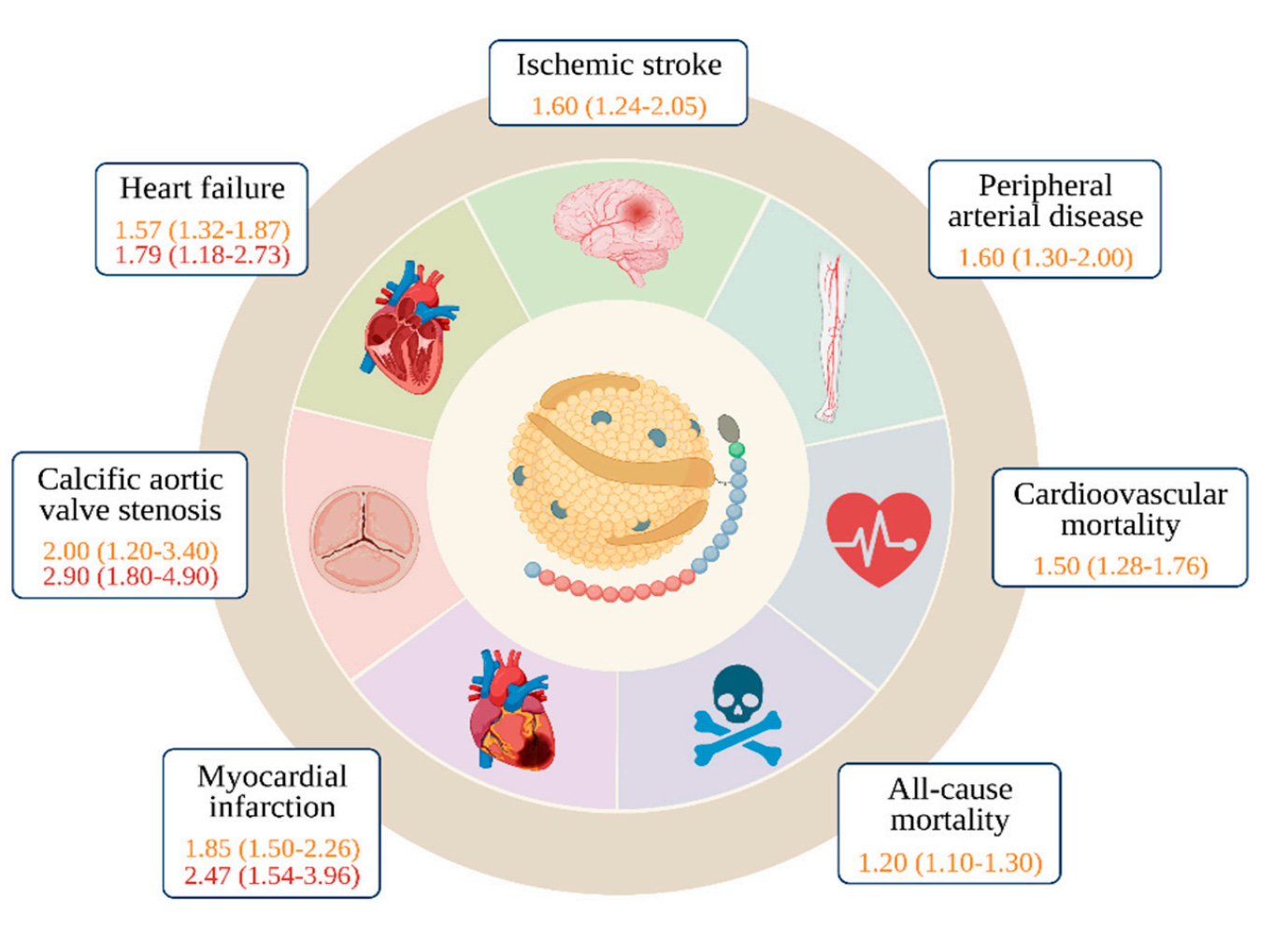

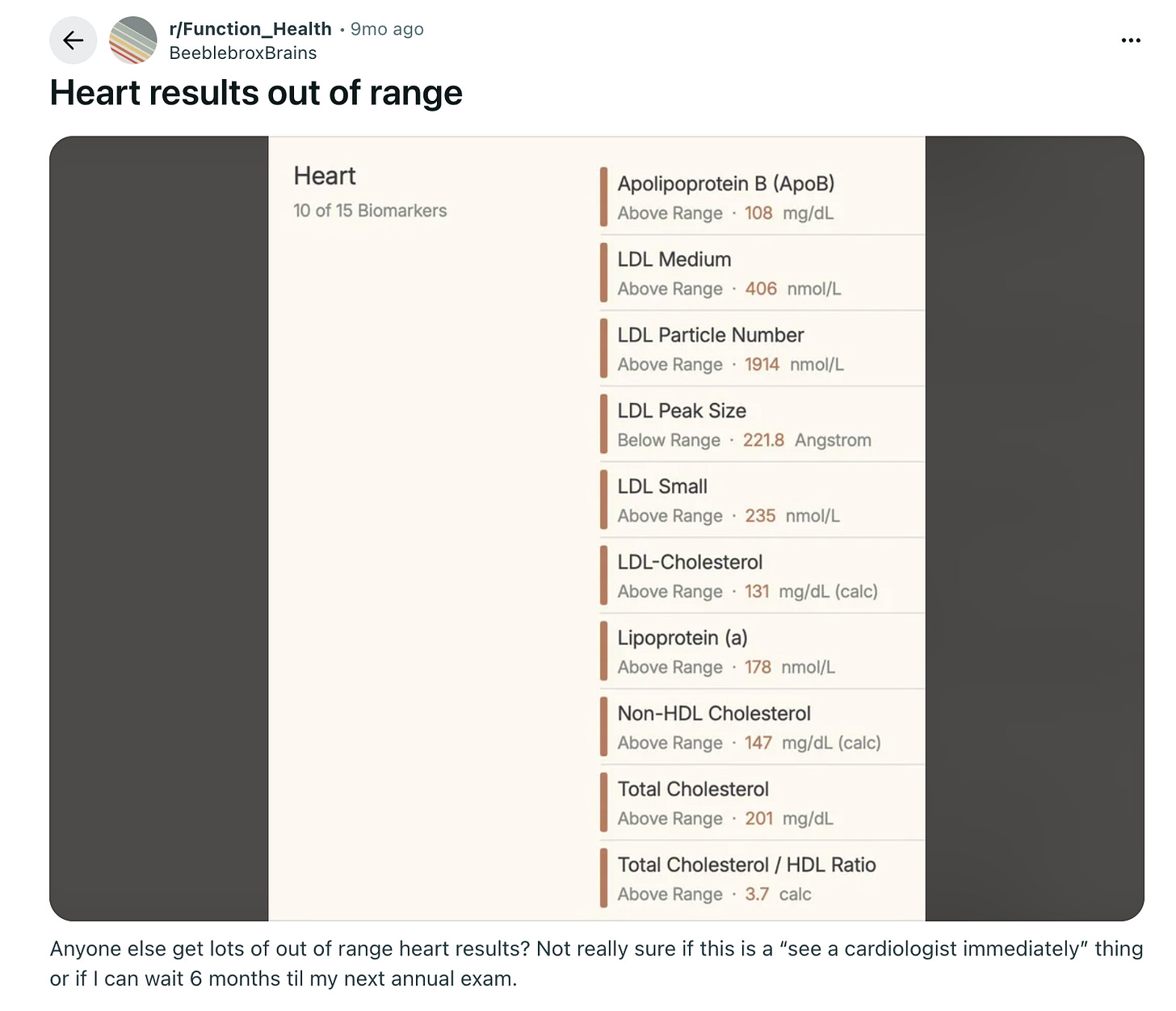

The problem is that while D2C is building an excellent top of the funnel, they are squandering the potential these tests open up downstream. If roughly 20% of the population has elevated Lp(a) levels, that means Function alone is surfacing around 50,000 people who need to see a lipidologist or preventative cardiologist.

But are they actually going to see a specialist?

The fact that someone can pay $500 for a test, get a “scary” result, and then be left to figure out the next steps on Reddit is, frankly, insane.

What I see happening next year is companies monetizing the patient journey in two ways. First, by building referrals to cardiology clinics with specialists who know how to manage an Lp(a) of 180 nmol/L and charging a nice, hefty referral fee.

Private clinics would certainly kill for this kind of customer acquisition, which essentially costs them nothing, while patients would gladly pay to skip the anxiety spiral of researching their results through LLMs, dealing with insurance phone trees, or finding preventative cardiologists in their area.

And second, when Lp(a)-lowering drugs hit the market, someone has to find the patients. D2C companies will have 50,000+ of them pre-identified and waiting. That’s a wonderful data set that pharma will want to secure before a mega-blockbuster launch, which Pelacarsen may turn out to be.

HIMS CROSSES THE ATLANTIC

2. Battle of the deepest pockets

I deleted my Instagram a few years ago because I like my attention span, so my girlfriend showed me the Hims & Hers ad that appeared after she scrolled for maybe 30 seconds. Then there was another, and another, and another. They’re certainly not tiptoeing into the UK.

In my view, this is a bet on narrative as much as it is on revenue. Hims needs Wall Street to see a diversified telehealth platform in multiple international markets and not just a compounded semaglutide company that’s one FDA enforcement action away from capitulation.

However, the private UK GLP-1 market is a very cut throat place to enter right now and my inbox is a good barometer of just how competitive things have become.

Every week there’s another discount code or referral bonus and providers trying to undercut whoever sent the last goodie. The issue is that when you’re all selling the same drug at similar margins, price is one of the few levers left to pull.

It also doesn’t help that Lilly’s 170% price hike on Mounjaro has forced tens of thousands of patients off treatment, and unlike the US, there’s no ‘regulatory grey area’ to exploit, so Hims will be selling branded drugs at branded margins, competing against established players with existing relationships.

Nonetheless, given the US balance sheet, Hims will disrupt the UK market.

Here’s what I expect to happen:

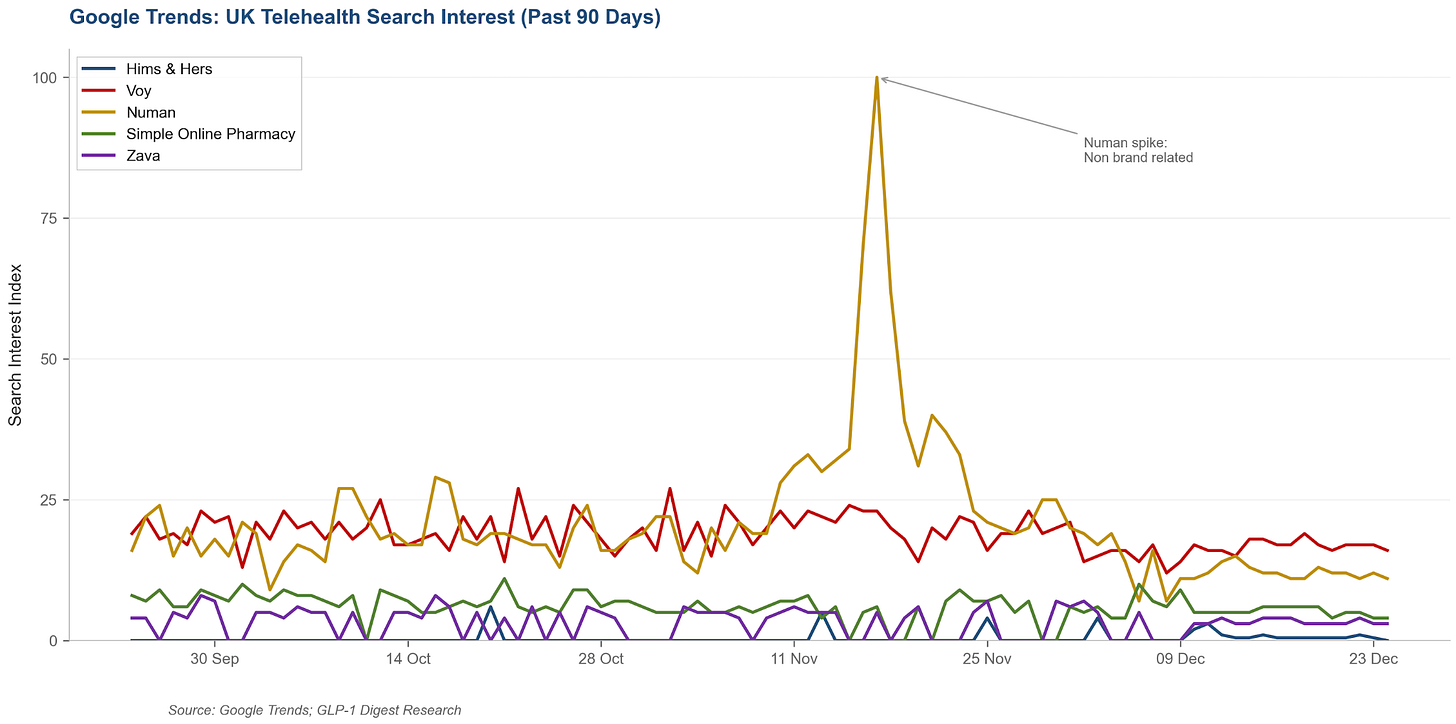

Hims & Hers will execute a scorched earth advertising blitz between now and early 2026, timed perfectly for the “new year, new me” window. Their approach will be similar to what made them so successful when they launched GLP-1s in the US: focus on paid channels like Google search for GLP-1 and weight-loss keywords, Meta and TikTok social campaigns, and influencer/affiliate partnerships to capture attention and convert new customers quickly.

Since Hims can splurge in this area, CACs will generally rise across the category. However, the impact will be most significant for direct competitors, specifically, premium branded players with slick UX and strong clinical positioning, like Voy.

Both companies target the same higher-income, convenience-oriented segment, and both are pushing Wegovy to customers. As a result, auction competition for these users will intensify, and increase Voy’s payback period while reducing their LTV/CAC in the near to medium term.

This will undoubtedly put pressure on Voy’s acquisition strategy. Either they find efficiencies in improving conversion optimization on their consultation forms (making them shorter or rewording them to make them more accessible), or they lean even more into the discount arms race.

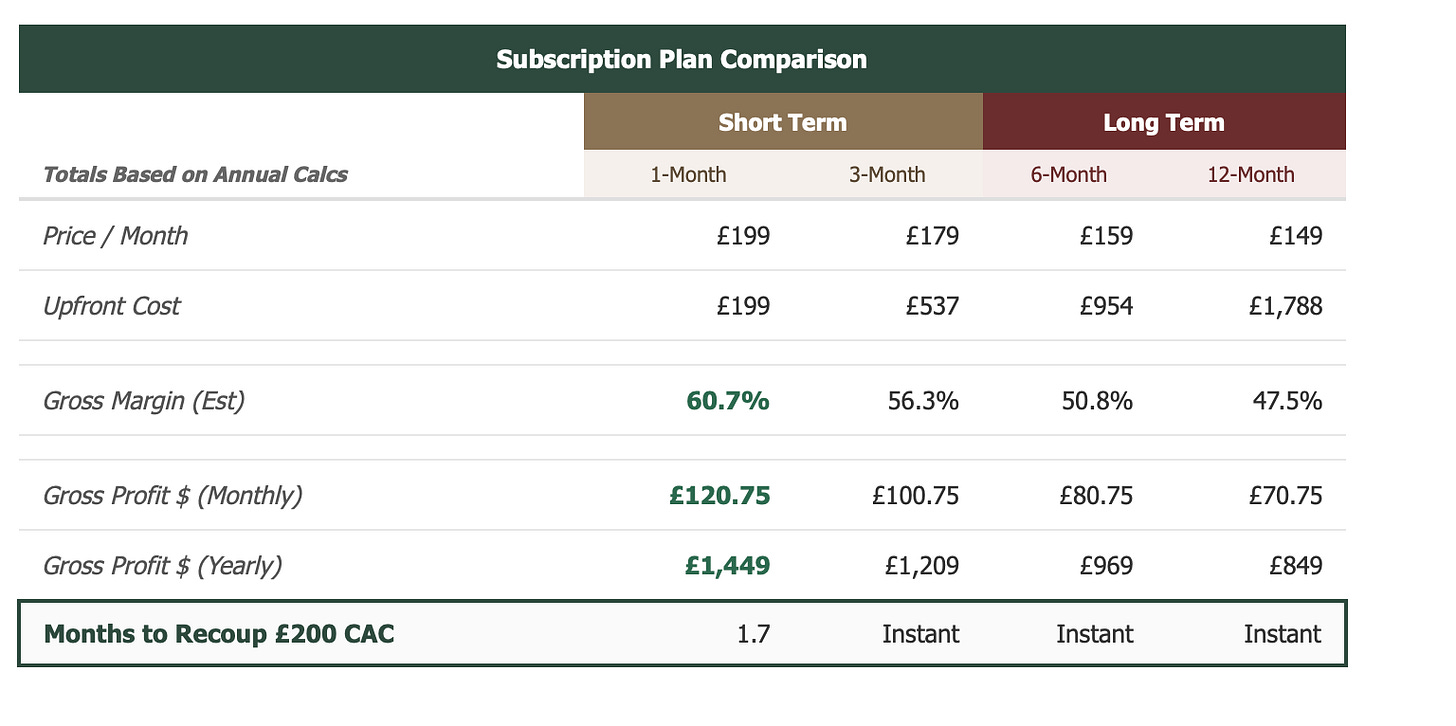

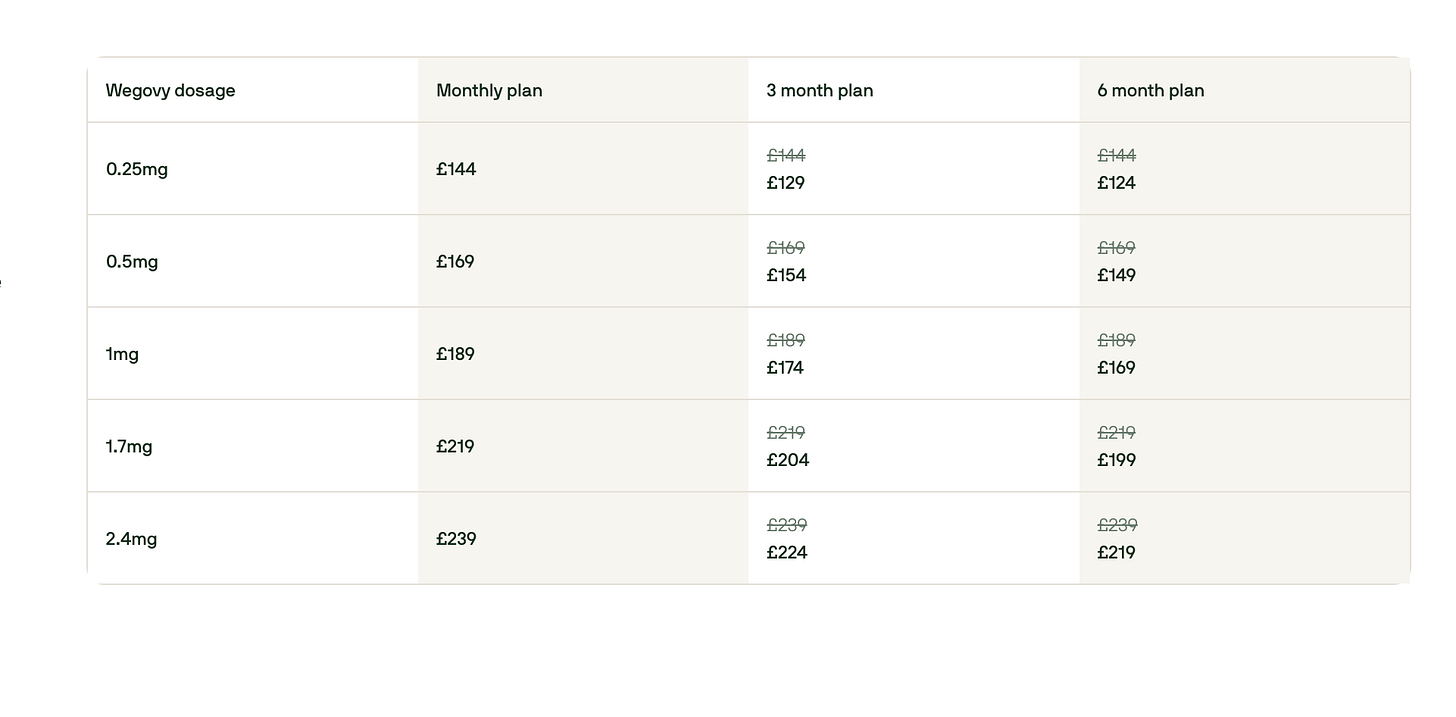

But what makes Hims particularly dangerous is the speed at which they recover their acquisition costs. A Hims customer on a 3-month plan pays once and can titrate from 0.25mg to 0.5mg to 1mg as needed.

Voy, on the other hand, bills monthly and charges more as you go up. That’s a very different value proposition because Hims locks in the cash upfront and gives you room for dosing flexibility, while Voy gets paid back slowly and charges you more for up-titrating the dose.

In my view, this is a classic Silicon Valley SaaS-style pricing strategy, which ensures the unit economics are favorable and allows Hims to pour the surplus back into acquisition and outspend competitors to win market share.

The critical question is: how many UK consumers are willing and able to pay upfront in a market that’s historically price-sensitive and not used to US-style pricing? While the cash inflow definitely provides Hims with the ability to outspend competitors and capture premium users early, adoption might actually be constrained if consumers hesitate to commit to upfront payments.

My guess is we’ll see Hims adjust because the UK market is just very, very different. I wouldn’t be surprised to see them introduce lower monthly charges or lower the commitment threshold to capture the price-sensitive middle.

THE TWO OBESITY MARKETS

3. All hail, Reta

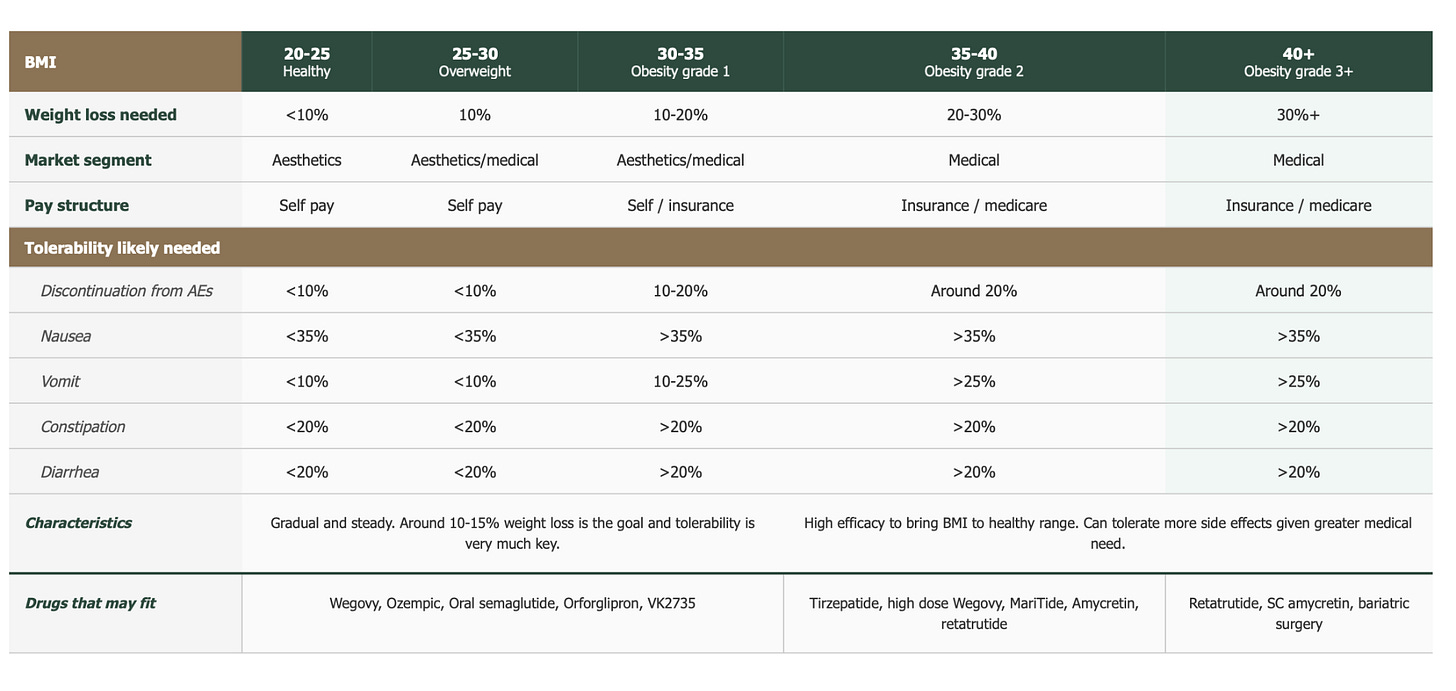

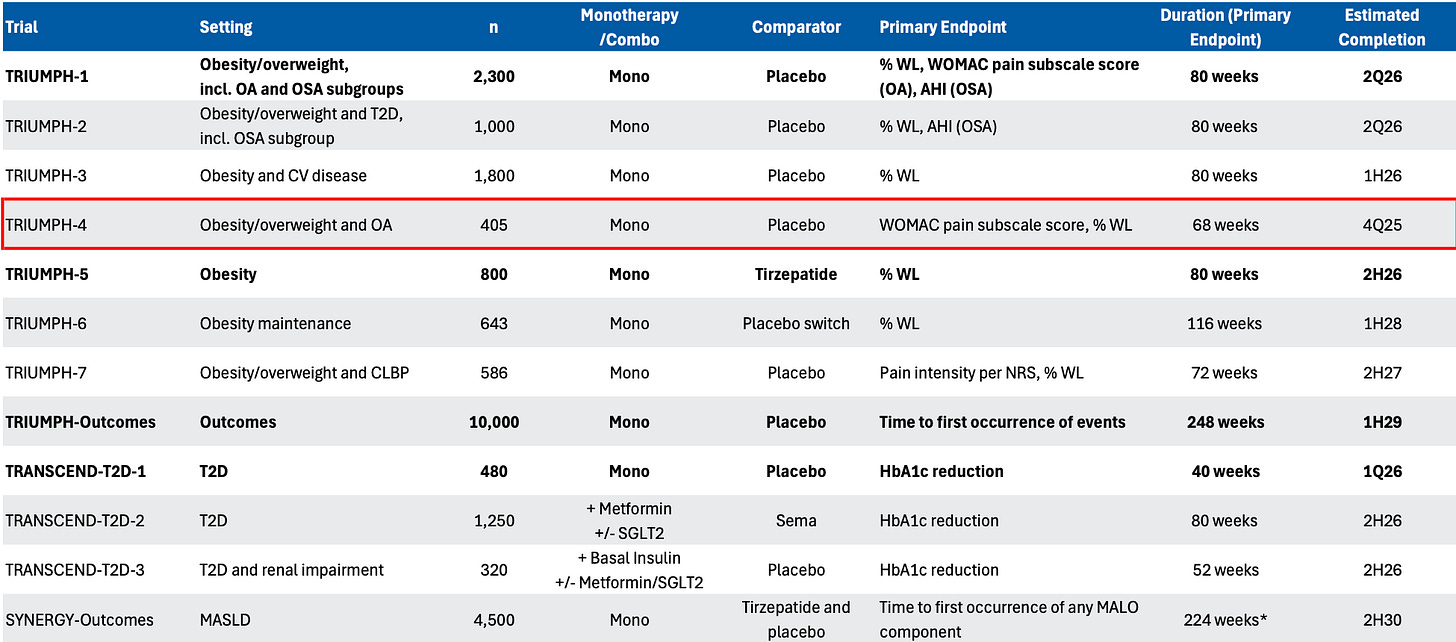

TRIUMPH-4 is validating my thesis that the global obesity market will segment into two: i) a consumer/aesthetics segment where weight loss efficacy and tolerability are equally weighted, and ii) a medical segment (BMI ≥35) where patients will accept a higher side effect burden for greater weight loss.

Some key nuances in the readout support my view.

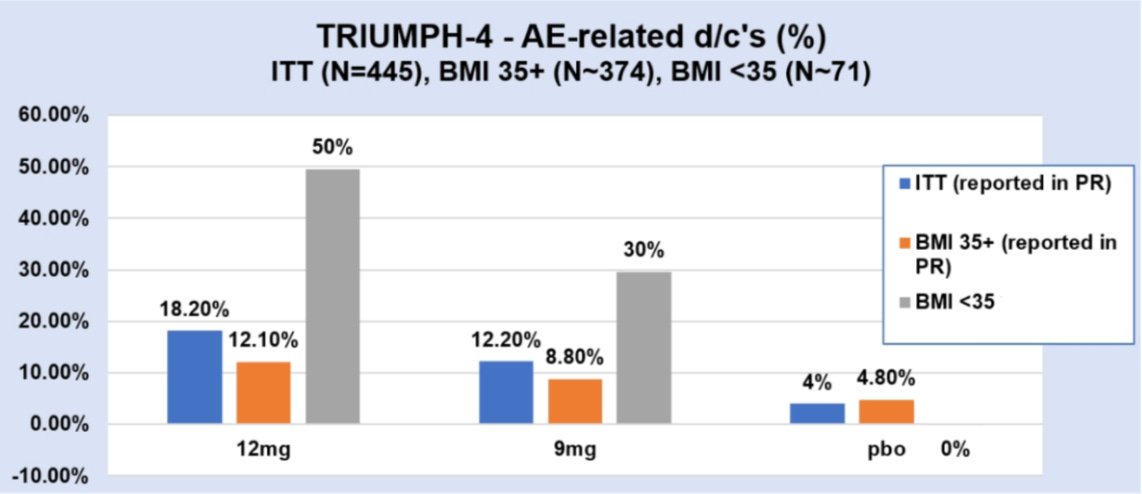

The trial enrolled around 405 patients with BMI ≥27 into three arms: retatrutide 9mg, retatrutide 12mg, and placebo. All were dosed weekly for 68 weeks, and the co-primary endpoints were change in body weight and change in knee osteoarthritis pain.

The headline weight loss being reported in all the news reports was 26-28%. But, for greater clarity and accuracy, I always focus on the intention-to-treat figure (ITT) which counts whether every patient who started the trial finished it or not. On ITT, weight loss was 20% and 24% at the 9mg and 12mg doses.

Once you subtract the placebo (you want to get the true effect of the drug), you get 15-19%, respectively.

That certainly looks underwhelming compared to the headlines, and the key point I want to stress is that the ITT was dragged down because patients with BMI <35 dropped out at much higher rates.

In fact, the dropout rates I calculated suggest that nearly 50% of patients on the 12mg dose with BMI <35 discontinued. That is a staggeringly high number! And there are a few reasons for it.

First, some patients hit a BMI cutoff of 22 and had to stop the trial. This means the drug was so effective that it pushed people into territory where continued weight loss would be unhealthy. In my view, that makes it a poor fit for patients who need moderate, controlled weight loss and also suggests that retatrutide isn’t a viable maintenance option for lower-BMI patients. You can’t stay on a drug that won’t stop — and from what I’ve heard, there was no reported weight loss plateau either, even at 68 weeks.

Second, tolerability. Patients with a BMI <35 are less likely to ’put up’ with side effects, and, given the high vomiting and nausea rates (compared to tirz), the risk/benefit ratio is unlikely to be perceived as ‘worth it.’

Now compare this to patients with BMI ≥35, of which only 12% discontinued. My feeling is that these patients stayed because the payoff justified the cost. When you’re facing severe obesity such that you struggle to even tie your shoelaces, you’ll tolerate a lot more to get 25%+ weight loss. Therefore, the side effects almost become a price worth paying.

I expect TRIUMPH-4 to be the first datapoint in a pattern repeated across 2026’s readouts. TRIUMPH-1 (due Q2 2026) enrolls a broader obesity population with no comorbidity requirement over 80 weeks. If my thesis holds, we should see even higher weight loss — likely north of 25% — among BMI ≥35 patients, and similar or higher dropout rates among lower-BMI patients. By this time next year, we’ll know whether the obesity market fragments or whether one drug can serve everyone.

I’m betting on the split.

THE END OF DRINKING?

4. Can GLP-1s solve obesity and alcohol problems?

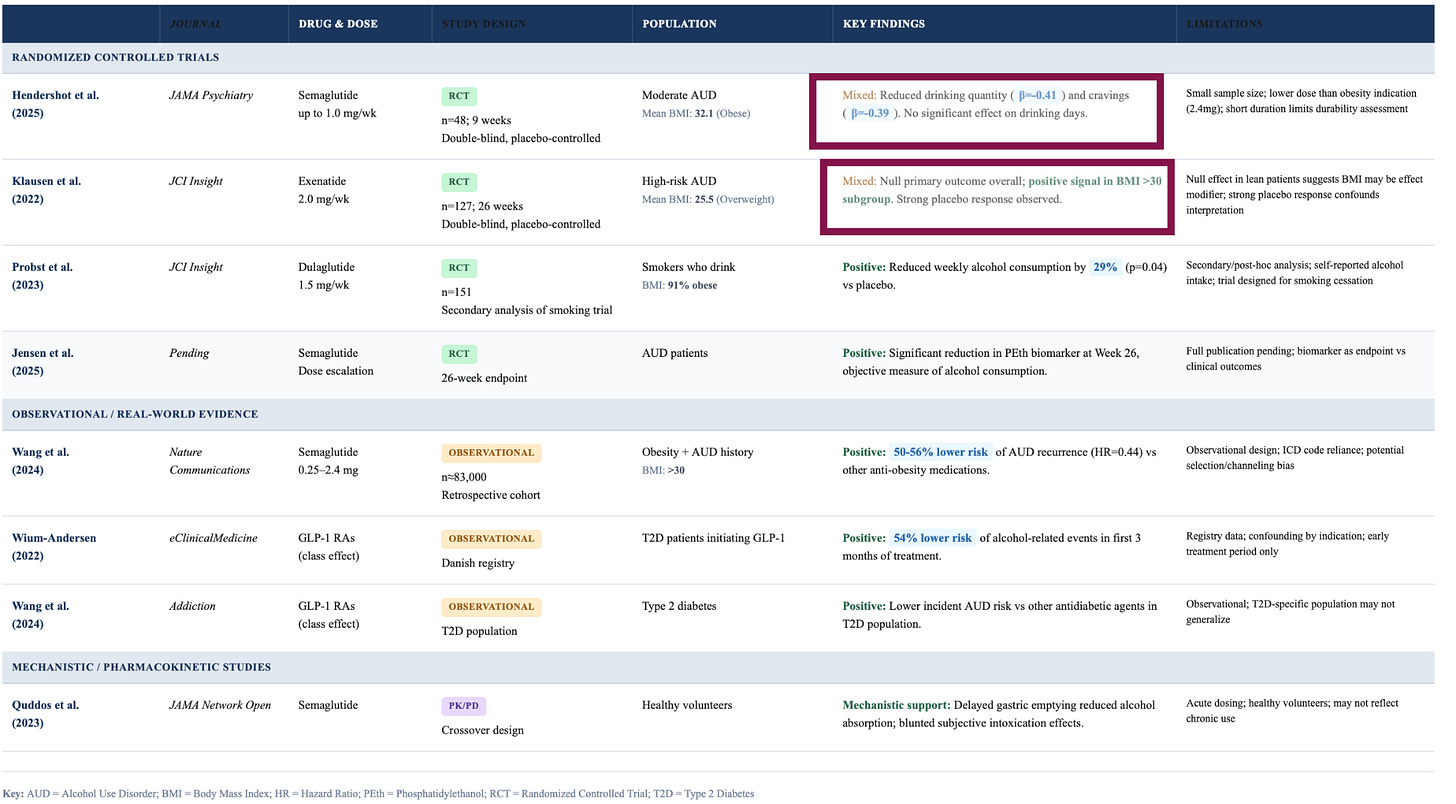

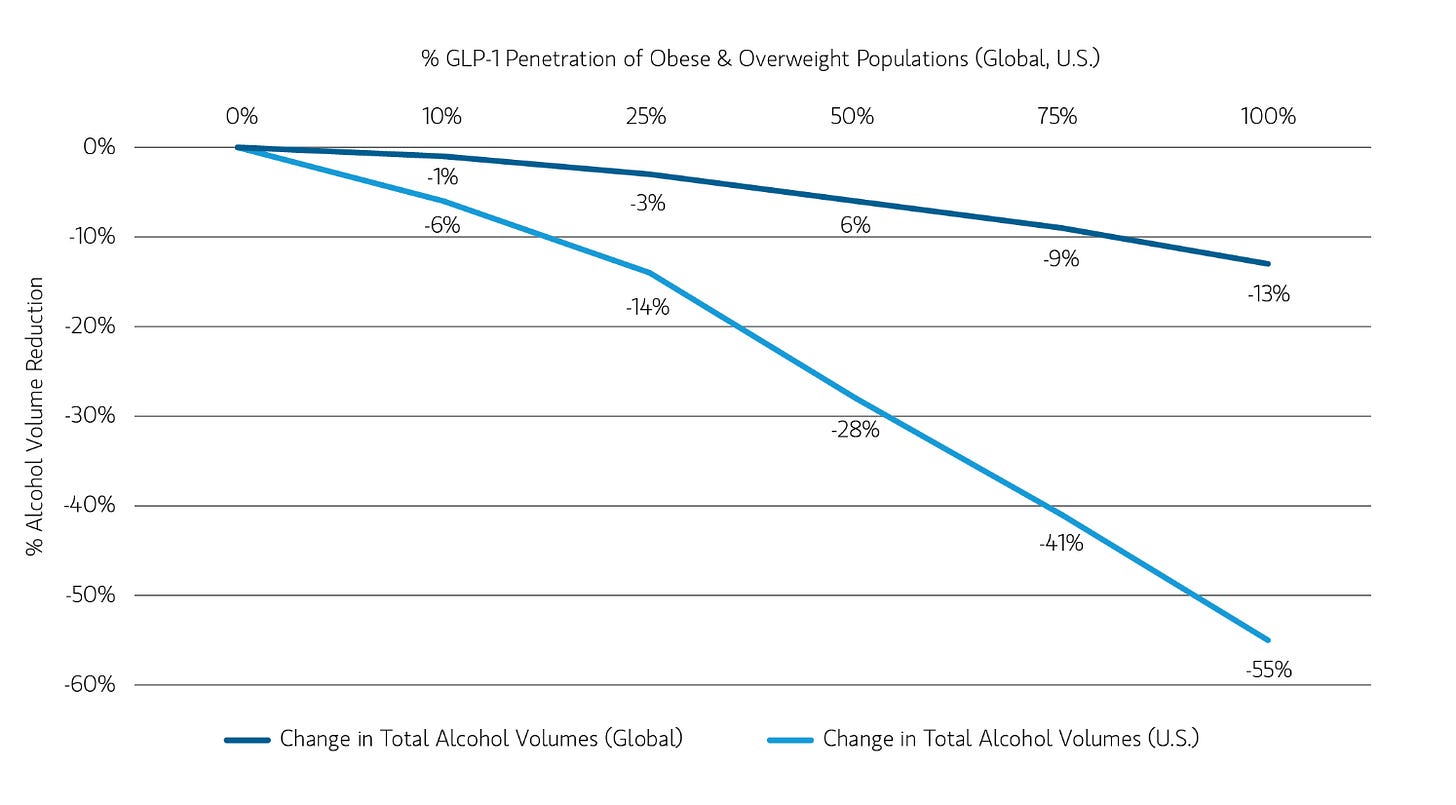

According to Morgan Stanley, yes. A recent report projects that if all of the obese and overweight population in the US took a GLP-1, alcohol volumes would plummet by 55%! The assumption is that the effects of the medication are real and persistent over time and would make users cut down on drinking by at least 75%.

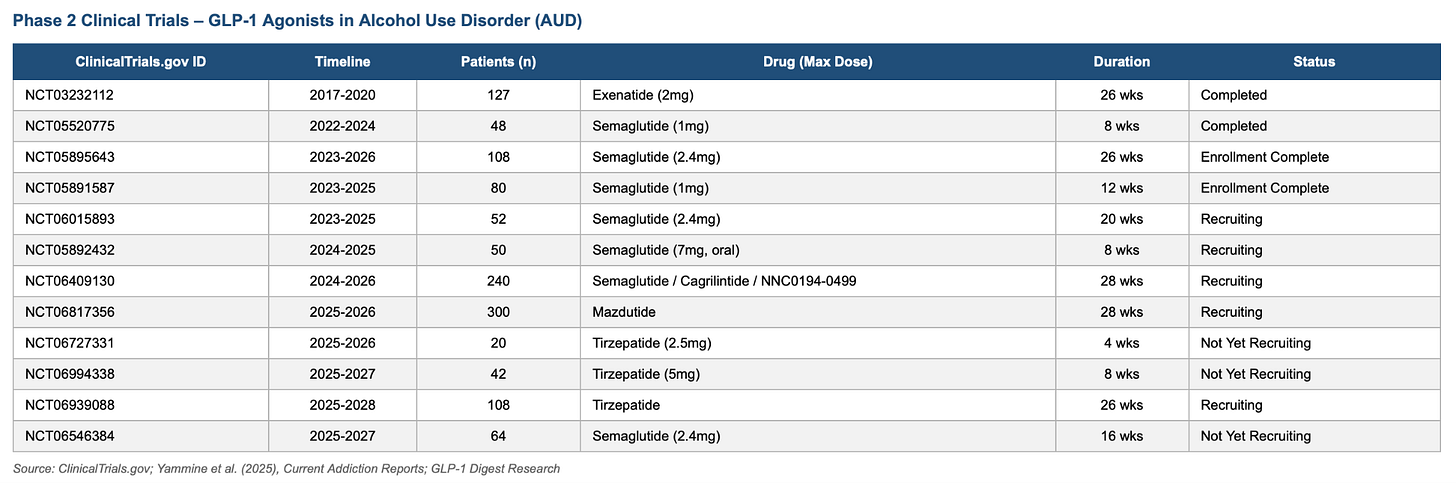

In my view, that’s quite a stretch, given that we have no idea why GLP-1s might reduce alcohol intake in the first place, and the clinical evidence so far doesn’t clarify things. Whether Morgan Stanley is right depends entirely on this mechanism.

If GLP-1s directly dampen dopamine pathways in the brain, reducing the craving for alcohol at a neurological level, then, yeah, that’s a real, persistent effect that will have a tangible impact on alcohol sales.

If they delay gastric emptying and slow down the speed at which alcohol hits your bloodstream, making each drink feel less rewarding, that’s also a durable effect that’ll impact alcohol sales. But, if people are just drinking less because they feel nauseous and crappy on these drugs, then the effect will fade as they adjust to the medication. The gin and tonics will inevitably return.

We don’t know which one it is, or which segments of the population are affected. In Randomised controlled trials (the studies which show causality), semaglutide led to a 30-40% reduction in drinking among people with alcohol use disorder, but exenatide, another GLP-1, had no overall effect!

The real-world data also hints at no effect on alcohol sales over the long term. A Cornell study tracking 2,600 US households over a period of 6 months found no significant change in alcohol purchases among GLP-1 users. Similarly, Jefferies, the investment banking firm, ran a 3,600-person survey and found that only 2% of those drinking less cited GLP-1s as the main reason.

Several trials are underway to untangle this, and with any luck, we’ll get some clearer readouts next year.

In my view, I think the impact of GLP-1s on alcohol is overblown. The senior leadership teams at Diageo and Co. have more pressing concerns to worry about, like cannabis or the fact that people are becoming increasingly health conscious because of the devices they are wearing.

Reflecting on my own drinking, I’ve become a near teetotaler since buying my Oura ring—I hate watching alcohol destroy my REM sleep, and as a result, I only drink on very special occasions. I suspect I’m not alone, and the shift has nothing to do with GLP-1s.

PAY NOW, SAVE NEVER

5. Gene therapies that eliminate the need for drugs entirely

I’ll be spending more time researching and covering one-and-done therapies in the cardiovascular and obesity medicine spaces. Essentially, these are treatments that cure the underlying disease through innovative and novel gene editing techniques, eliminating the need for medication entirely.

In my view, these treatments represent the biggest shift in how we think about incentives and payment structures. Will a payer like the NHS front £200-500k today for a treatment that might not save them money for another twenty years? Will a US employer, averaging a churn rate of two-ish years, cover gene therapies only for another company to reap the benefits?

These are the questions that make this space so fascinating.

Two companies have caught my eye right now. If they have successful readouts, it will have a gigantic impact on how we think about chronic diseases.

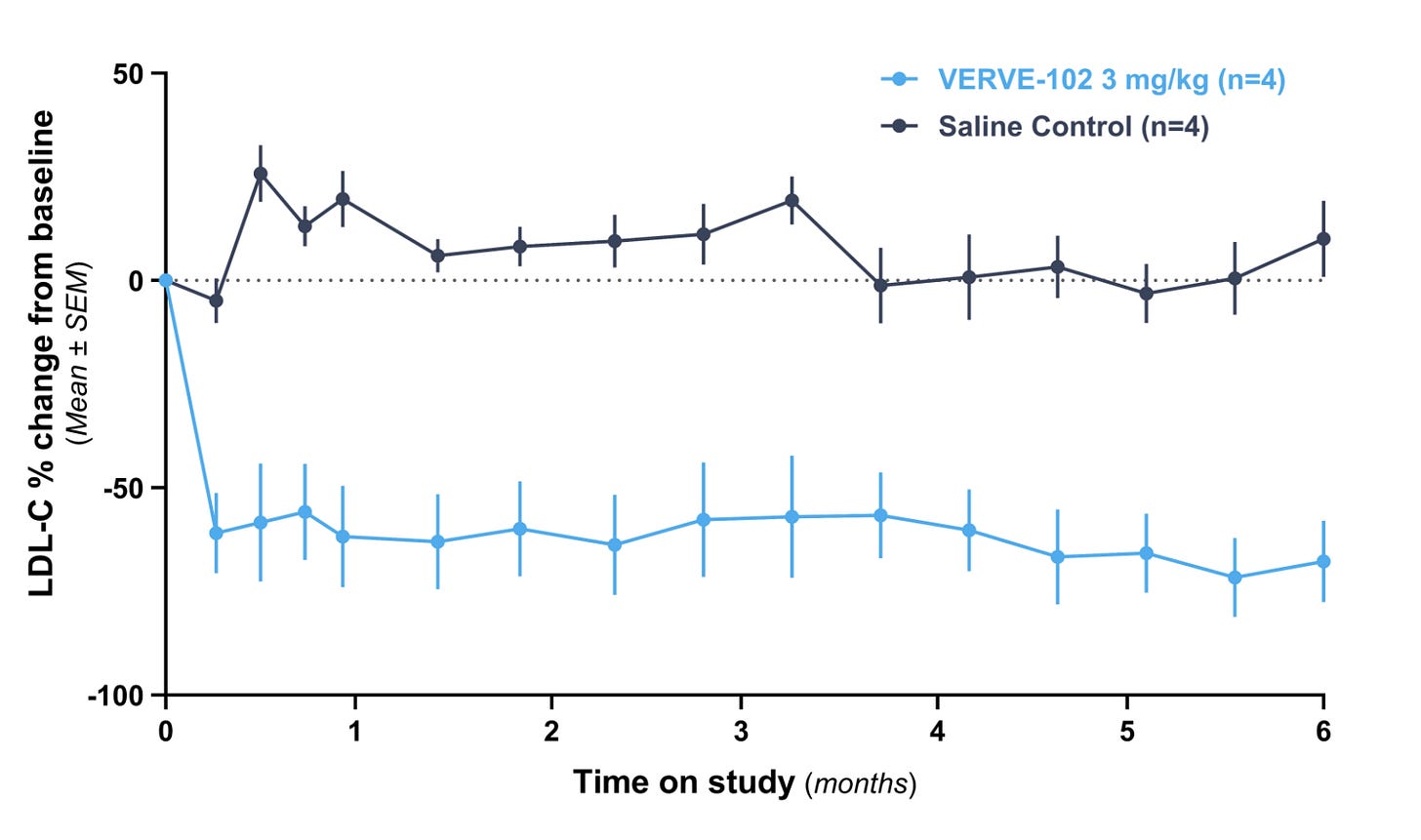

Verve Therapeutics is using in vivo base editing to permanently inactivate the PCSK9 gene, lowering LDL cholesterol with a single infusion. High LDL-C is one of the primary drivers of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, which is the leading cause of death globally. Statins and PCSK9 inhibitors are effective, but only if patients keep taking them.

Verve’s betting that permanently editing the gene enables them to cheekily side-step the adherence problem entirely, and Lilly also agrees with this gamble, acquiring them in June 2025 for $1.3 billion.

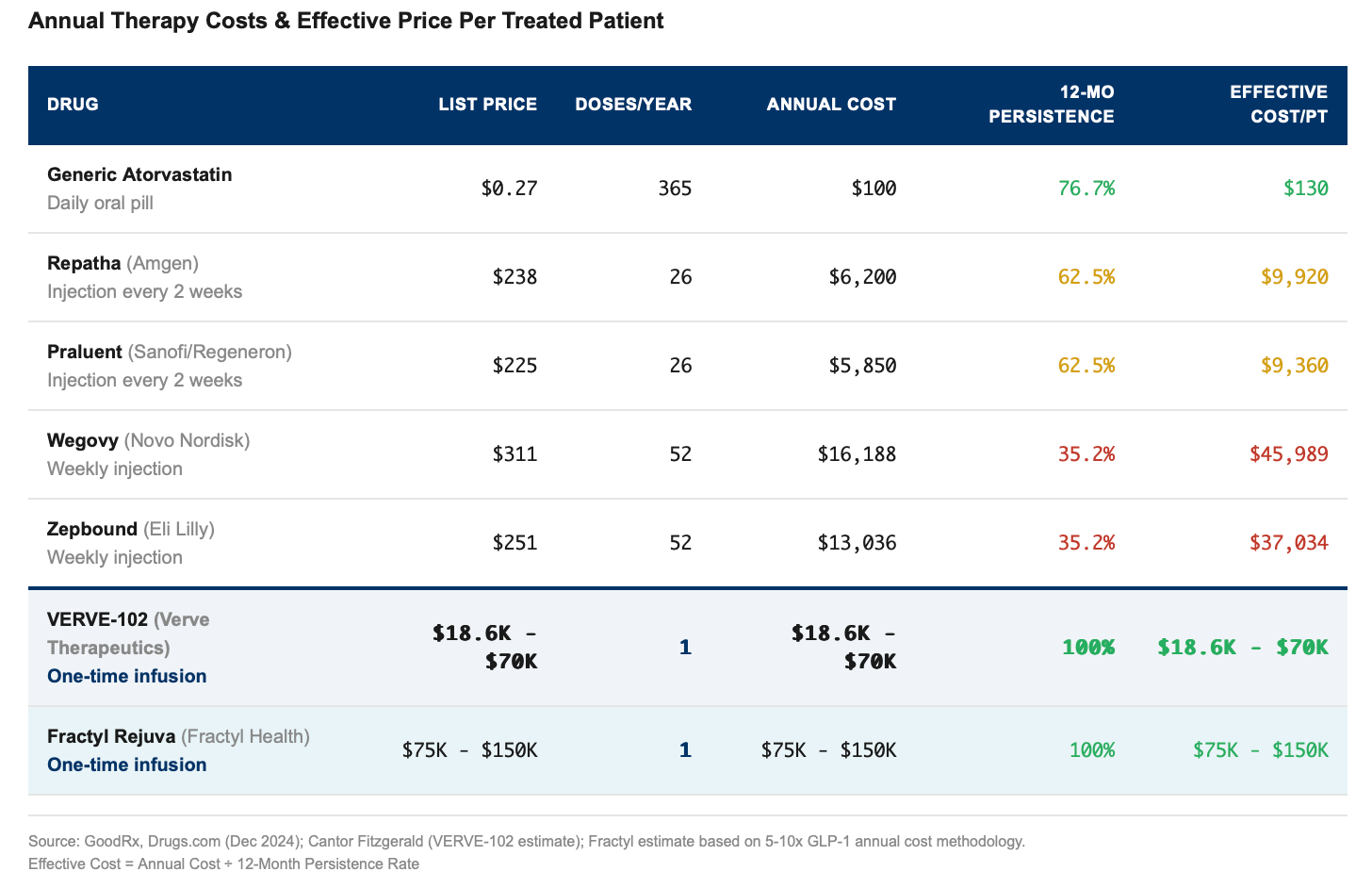

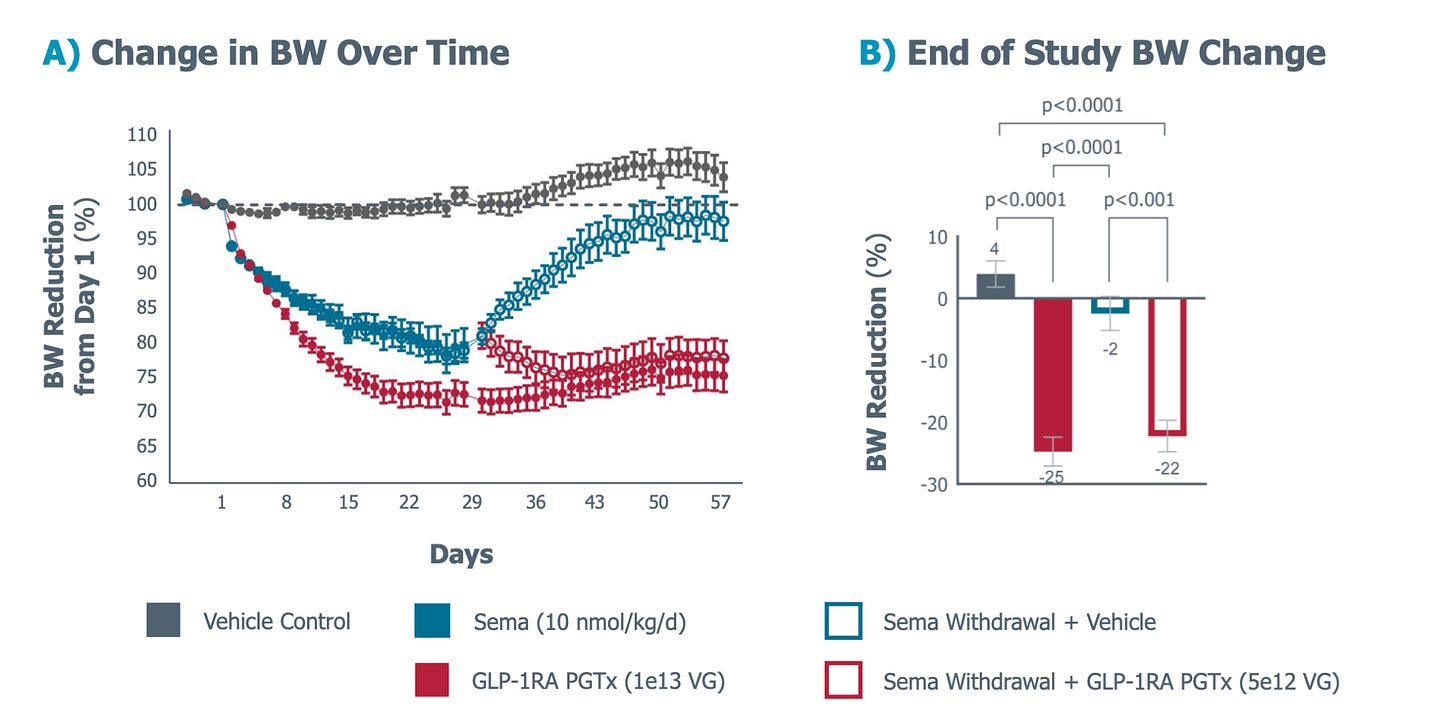

Fractyl Health is developing a GLP-1 pancreatic gene therapy that will turn the pancreas into an endogenous GLP-1 producer. They’re positioning the treatment as a one-and-done for weight maintenance, and for the millions of people currently injecting Wegovy every week, this could mean no more costs piling up month after month, making it an enormously attractive proposition.

So what should these therapies actually cost?

Through some assumptions on my end, I’ve estimated that one-and-done therapies should be priced at roughly 5-10x the annual list of current drugs in the market, but I still think that’s conservative. If these treatments deliver permanent results and address TAMs as massive as cardiovascular disease and obesity, the pricing conversation should start at north of $1 million per dose.

The reason why is because of adherence.

Only 35% of patients on Wegovy or Zepbound are still taking them after 12 months, while the rest quit, which means payers are subsidizing treatments that never actually ‘work’ because the patient stopped the meds. It’s like buying ten gym memberships but only three decide to go, which effectively means you’re paying $150 for each person who actually uses the gym. Not very cost effective!

And is why insurers balk when Wegovy’s $16,000 annual price balloons to nearly $46,000, and Zepbound’s $13,000 becomes $37,000 per person.

One-and-done therapies don’t have this problem of course. VERVE-102 might cost $18-70k and Fractyl might run $75-150k, but 100% of patients who receive the treatment actually get the benefit. There’s no need to worry about adherence because there’s nothing to adhere to, and on that basis, $150,000 might actually be a bargain.

Anyway, that's what I'll be watching in 2026. I'm curious what you're thinking about. What surprised you this year? What's on your radar for next year? If you reply to this email, I'll reply back. I read everything !!