Why Your Ozempic Won't Cost More–Even With a 200% Tariff

With Novo and Lilly locked in a market share battle, neither can risk price hikes—even with tariffs looming

If you've browsed r/ozempic lately (home to nearly 120,000 users), you'd think the U.S. was facing a GLP-1 apocalypse. Threads about a potential 200% U.S. tariff on Ozempic, Wegovy, and Zepbound have sparked fears of shortages and warnings of $2,000 monthly price tags from Hims and Hers. People are already stockpiling in panic—a standard fridge can hold 87 Ozempic pens if you sacrifice the butter compartment, or so I’ve been told.

But it’s not just Reddit doomsayers sounding the alarm. Major news outlets like Forbes and AOL are warning millions about astronomical out-of-pocket costs for GLP-1 medications that simply will not materialize, even under the worst case tariff scenarios.

To understand why, we need to look at three key forces: Tariff math, pharmaceutical companies’ fat margins, and a two-company price war—all of which means your Ozempic bill stays put.

Tariff math

Trump's drug tariffs are coming, and faster than you'd think. Washington insiders say we're looking at a 2 month timeline before duties up to 200% slam foreign-made Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (API) entering U.S shores.

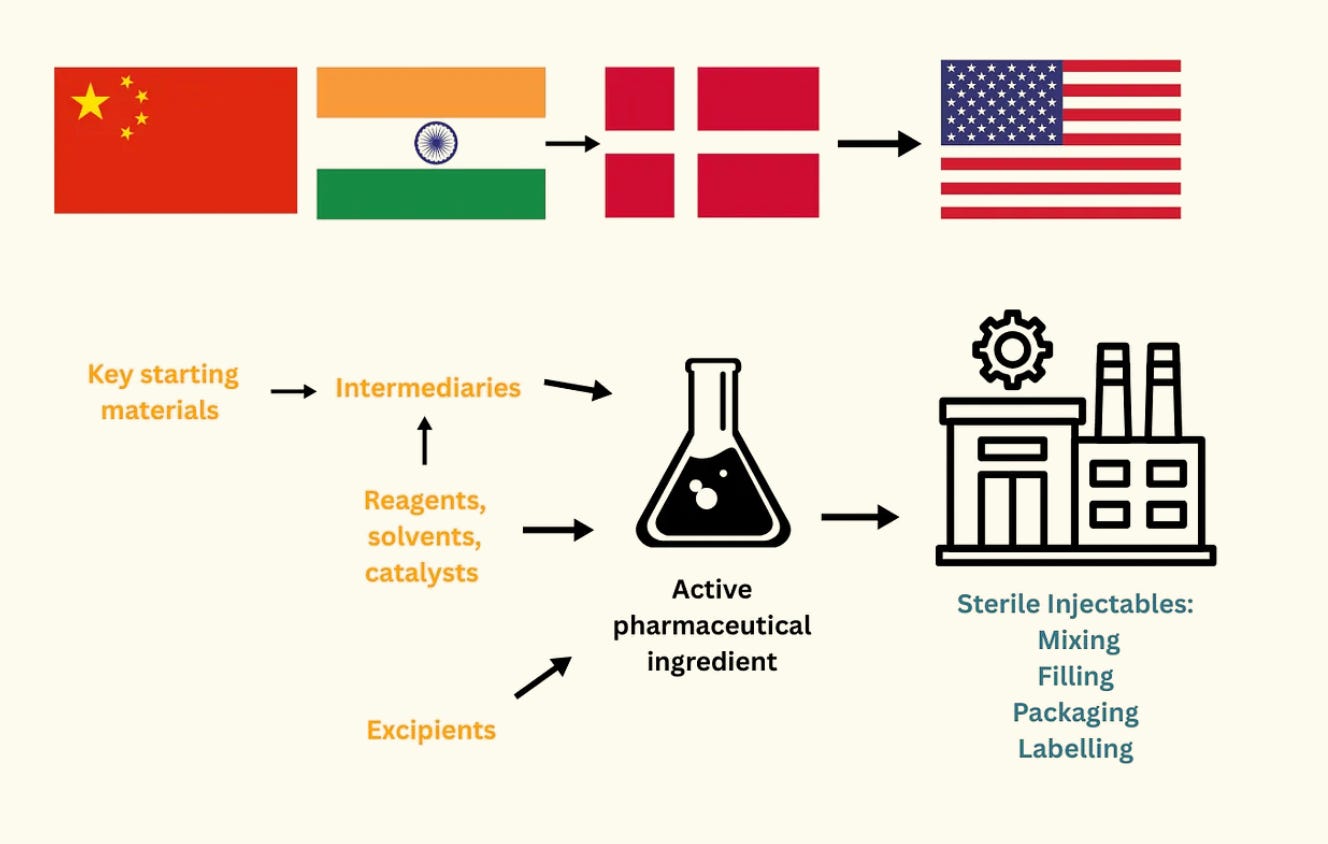

This puts both Novo and Lilly squarely in the blast zone. Novo Nordisk manufactures semaglutide—the API in Ozempic and Wegovy—in Denmark, while Lilly produces most of its tirzepatide API for Mounjaro and Zepbound in Ireland.

Before you start panic-buying Ozempic pens, let's talk about what these tariffs actually mean for your monthly prescription costs. When you see the words '200% tariff' you might be thinking, “Great, my $1,300 Ozempic prescription is about to cost $3,900.”

But U.S. Customs doesn’t touch the retail price you see at your local pharmacy. Trump’s, tariffs will only tax the wholesale transfer price—the invoice Novo Denmark writes to Novo USA when Semaglutide crosses the Atlantic.

By law that invoice must resemble what Novo would charge an unrelated buyer (regulators call this ‘arm’s-length’ pricing).

This exact number is hush-hush, but analysts who reverse-engineer Novo’s cost structure estimate it to be around “$100” per monthly dose1.

Now, multiply whatever percentage tariff you like onto that $100 transfer price. Even the harshest scenario—200%—adds just around $200 per monthly dose. A milder 25% duty is more like $25.

This is a drop in the bucket to both pharmaceutical giants, which have gross margins north of 80% on GLP-1 medications.

Margins & the three‑lane U.S. market

So, what exactly are the margins? Well, the manufacturing cost for a month's supply of injectable semaglutide is anywhere between $0.89 and $4.73, according to research published in JAMA Network Open. This means the company sells a $5 product for $1,349 at retail—a stunning markup exceeding 27,000%.

Of course, critics will counter: “Sure, but drug development costs billions.”

Yes, drug development costs billions. But if R&D alone determined price, semaglutide would cost roughly the same everywhere. It doesn’t. Semaglutide (Wegovy) sells for about $250 to $376 in the U.K. and roughly $183 to $323 in Germany, yet Americans pay nearly 5 times more.

Why such an enormous difference? It comes down to buying power. Most rich countries act as a single, hard‑nosed buyer, like Britain’s NHS. These national governmental orgs set firm price limits.

In the U.S., pharma manufacturers can set whatever list price (the wholesale acquisition cost) they want because no federal agency imposes a ceiling. This laissez-faire pricing means Novo and Lilly harvest the lion’s share of their GLP-1 profits in America—the American patient effectively subsidizes lower costs for the rest of the world.

This profit-rich American market creates three massive revenue streams:

Cash-pay: Telehealth platforms such as Hims & Hers and Ro buy at the $1,300 list (wholesale-acquisition) cost and pass it straight to self-pay patients. No Pharmacy Benefit Manager (PBM), no rebate—so Novo and Lilly keep virtually 100% margin on every pen.

Direct: NovoCare and LillyDirect now ship pens straight to patients at a modest online discount, often $500-$800. There’s still no PBM taking a cut, manufacturing cost stays under $10, and gross margin remains close to 90%.

Insured: When large employer or state plans cover Wegovy or Zepbound, a PBM demands a confidential rebate, often $400-$500 off the $1,300 list— to secure preferred formulary placement. That trims the net to roughly $800–$900 per pen. Still close to ~80 % margin.

All that revenue translates into eye-watering profits.

Even at the worst-case, theoretical 200 % import duty, the hit is modest. By my estimates, Novo’s gross margin on a $1,349 Wegovy pen could slip from roughly 93 ¢ to about 78 ¢ on the dollar, while Lilly’s margin on a $1,086 Zepbound pen might drop from about 91 ¢ to 72 ¢2.

Scaled company-wide, that would trim margins only from 84.7 % to ~81 % at Novo and from 81.3 % to ~78 % at Lilly—more a speed-bump for shareholders than a price shock for patients, and still richer than the industry’s ~71 % norm3.

But, why not just pass these tariff costs to patients anyway?

In theory, they could. In practice, it would be brand suicide. Neither Novo nor Lily company can risk price hikes—otherwise, they would send patients (read: customers) straight to their rival.

This is because the GLP-1 market is red hot. The potential short-term profit from a price increase would be dwarfed by the long-term revenue loss from surrendering market share.

Instead, Novo and Lilly are now engaged in a manufacturing arms race, pouring billions into production to secure market dominance. The company that can reliably supply these in-demand medications will ultimately win—and in this battle, Lilly has positioned itself to gain the upper hand.

Capacity as the next battlefield

Eli Lilly is pouring $9 billion into a 600‑acre complex in Lebanon, Indiana. By late 2026, the site will ferment, purify, and fill tirzepatide end‑to‑end, churning out millions of Zepbound and Mounjaro pens each month. Those boxes will wear a “Made in USA—no tariff” label, a selling point with corporate benefit managers and the America‑first administration.

The plant also insulates Lilly from export bans or shipping hiccups, guaranteeing product flow when shortages hit.

Meanwhile, Novo Nordisk is struggling to catch up. It plans to expand its Danish semaglutide API hubs, but has only just broken ground on a fill‑finish plant in Clayton, North Carolina, due anywhere between 2027–29. Clayton will load pens, yet the bulk semaglutide will still sail over from Denmark—meaning tariffs will impact Novo for at least 4-5 more years.

This puts Novo on the defensive. If Wegovy’s or Ozempic’s list price crept up, Lilly could easily pitch: “Why pay more for an imported drug when our U.S.‑made Zepbound is tariff‑free and clinically stronger?” Major pharmacy benefit managers would flip their formularies overnight, patients would switch to Lilly’s cheaper alternative, and Novo would hand a fast‑growing rival the perfect marketing weapon.

Could This Dynamic Change?

The one scenario that could upset this competitive balance would be sustained supply constraints. If both companies hit manufacturing limits and can't meet skyrocketing demand, they might feel emboldened to pass tariff costs to patients. But even this seems unlikely—Pfizer and Amgen are already racing toward 2026/2027 launches to compete with GLP-1 medications.

Capitalism, Not Regulation, is Keeping Prices in Check

The fierce competition between two dominant players has created a pricing Mexican standoff: Novo can't raise Wegovy's price without hemorrhaging market share to Zepbound, while Lilly won't risk its hard-won momentum with price hikes that could give Novo an opening.

The irony shouldn't be lost here. The same free market that enabled these astronomical margins is now preventing them from climbing higher. Neither company will sacrifice long-term market dominance for short-term profits, especially with new competitors like Pfizer and Amgen waiting in the wings.

So while tariffs may sound apocalyptic, they're entering a market where the major players are already locked in a battle for supremacy. In this environment, absorbing tariff costs is simply the price of staying competitive.

Your Ozempic won't cost more next month. Not because of government intervention or corporate benevolence, but because neither giant can afford to blink first.

$100 transfer invoice is an analyst proxy. Novo and Lilly do not disclose it.

Numbers are directional, not GAAP audit figures; they show scale of impact rather than precise earnings guidance.

Methodology note

• Transfer price assumed ≈ $100 per pen (analyst proxy from China tender data and Novo’s 85 % margin).

• Cost-of-goods set at ≈ $5 (upper end of JAMA 2024 $0.89–$4.73 range).

• Tariff hit modeled as worst-case $200 (200 % of the $100 transfer value).

• List prices: Wegovy $1,349 and Zepbound $1,086.

• Margin math is per-pen, then scaled to company level; it excludes product-mix shifts, R&D amortization, and any future price or tariff changes.

Very informative.