Why Can't Anyone Stop Compounded GLP-1s?

Because federal, legal, and private forces won't allow it

For the past few months, I’ve been hearing all sorts of predictions about the compounded GLP-1 market collapsing. Supposedly, the FDA crackdowns are imminent, and litigation is going to rain down from the high heavens at any D2C telehealth provider who dares advertise the word “personalisation” with “GLP-1”.

It all sounds very apocalyptic. But when you actually look at what’s happening, the outcome is pretty obvious.

Compounding GLP-1s aren’t going anywhere. More than a million patients are turning to compounded options for cheaper, affordable access while insurers tighten coverage, and requests for prior authorizations multiply like gremlins in a storm.

Add in the political pressure to lower drug pricing, and you have a perfect tailwind that all but guarantees compounding to persist over the long haul.

Whether compounding is ethically defensible or medically safe is an entirely separate debate. I’m not cheerleading for compounders or defending Big Pharma. What I’m doing is examining the evidence.

So let’s set opinions aside and look at the facts.

But first, this edition is brought to you by Light-it.

Most dev shops will build whatever you spec. The best ones ask why you’re building it in the first place.

When you’re creating a healthcare product, that difference really, really matters.

You need engineers who understand that “move fast and break things” doesn’t work when you’re handling patient data, integrating with pharmacies, or supporting clinicians. Who knows why a clinical workflow can’t just mimic a consumer app. And, those who’ve already navigated HIPAA, FDA regulations, and hospital IT requirements.

Light-it are those engineers.

They partner with GLP-1 and weight-management startups to design and build secure, scalable infrastructure—fast. From onboarding flows and async visits to prescription routing, insurance checks, and refill reminders – they’ve helped multiple D2C telehealth companies ship products that work at scale, from MVP to series B and beyond.

The result?

Less time in Slack explaining HIPAA. More time shipping features patients actually use.

Building in health tech?

The supply is strangled but not cut off

In early 2025, a Brookings Institution report handed the FDA everything it needed to shut down compounding for good.

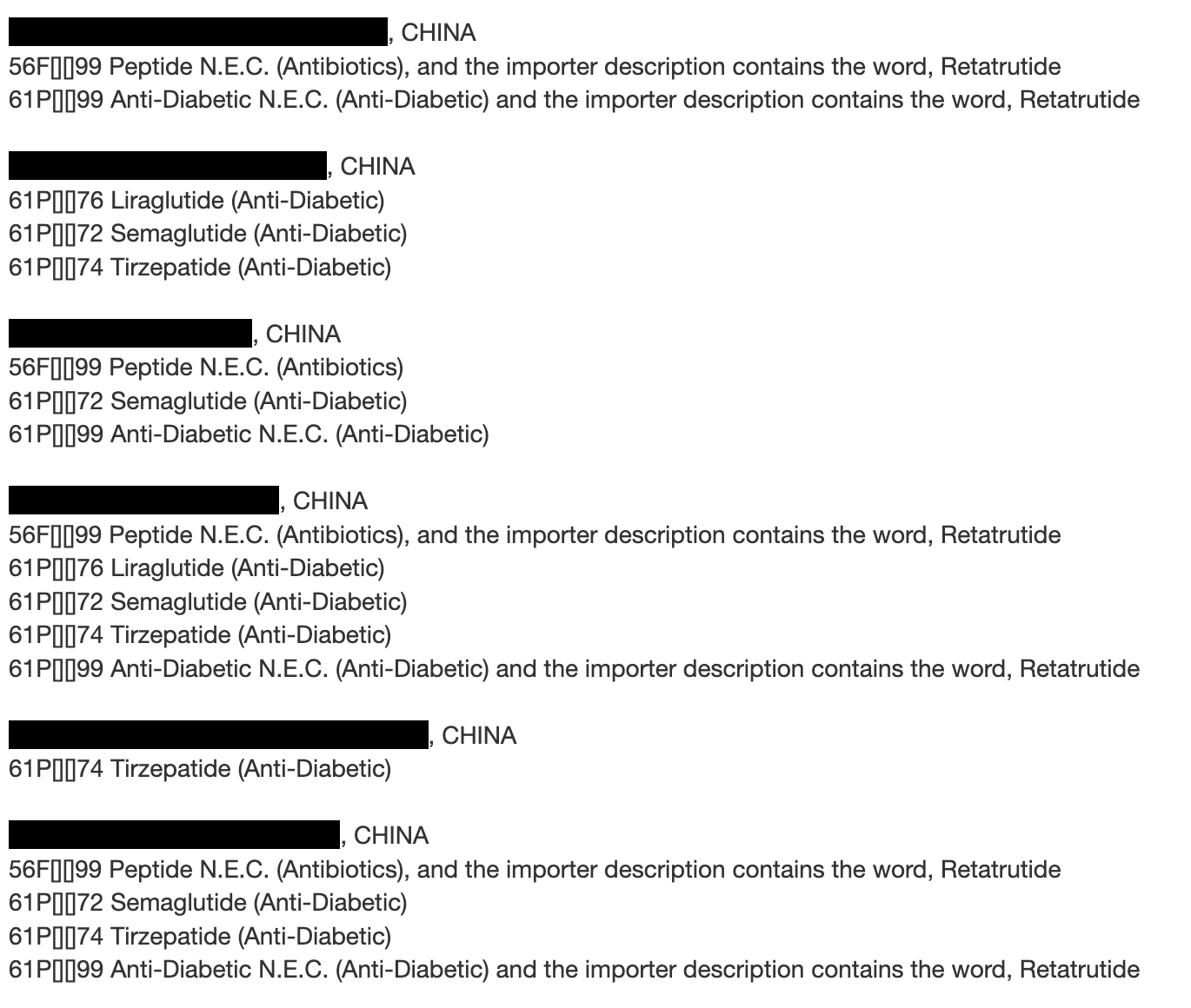

The report found that nearly all semaglutide API (active pharmaceutical ingredient) imported for compounding since June 2023 came from Chinese suppliers, and the majority had failed FDA inspections. Industry observers and big pharma executives widely expected an aggressive crackdown.

The FDA had many ways to turn off the compounding tap. They could’ve issued a blanket import alert and put every manufacturer on the red list1, choking off API supply at the border.

They could’ve added semaglutide or tirzepatide to the “Difficult to Compound” list, ending pharmacy production overnight. They could’ve even enforced Section 503A’s 5% out‑of‑state prescription cap and kneecapped the industry.

They chose to do none of these things.

Instead, the agency put out an import alert for GLP-1 APIs and immediately published a green list of approved overseas manufacturers, of which there are dozens.

In my view, this is implicit acceptance and accommodation of the compounding industry by ensuring the APIs entering the country are ‘safe’.

Would the FDA put guardrails on something they eventually planned to stop?

I don’t think so.

On closer look, the whole thing seems relatively toothless. Most 503a pharmacies are not under direct FDA oversight, and they don’t need to publicize their API sources. So the FDA list is just a little above the bare minimum of any enforcement.

Moreover, by stating the import alert “does not create any new limits on legal compounding of GLP-1 drugs,” the FDA has explicitly stated that pharmacies can continue legally compounding GLP-1s under the conditions already permitted by federal law.

As I argued earlier this year, it was wishful thinking for Novo and Lilly to bank on federal muscle given the political pressure to preserve access.

Legal recourse seemed to be the next best option, but alas, the gods seem to favour compounding in this case as well.

Mixed verdicts create tailwinds

Lilly’s and Novo’s legal strategy is relatively straightforward. Since they can’t ban compounding under Section 503A, they’re trying to strangle direct-to-consumer advertising which is the major source of customer acquisition for telehealth companies.

Because Lilly’s cases are on public record, we know their legal strategy uses three statutes to attack “personalized GLP-1” claims:

(1) The federal Lanham Act for false advertising between competitors. This is the core federal law allowing Lilly to sue competitors for commercial injury resulting from false or misleading advertising.

(2) State unfair competition laws (UCL). This broad state statute targets any type of business practice considered unlawful, unfair, or fraudulent.

(3) State false advertising laws. This specific state law prohibits untrue or deceptive marketing claims that have a tendency to confuse or mislead the public.

The endgame was to secure court injunctions blocking any claims of personalisation and safety and efficacy, which would force telehealth companies to either stop advertising completely or water down their messaging to the point where conversion rates drop from the face of the earth.

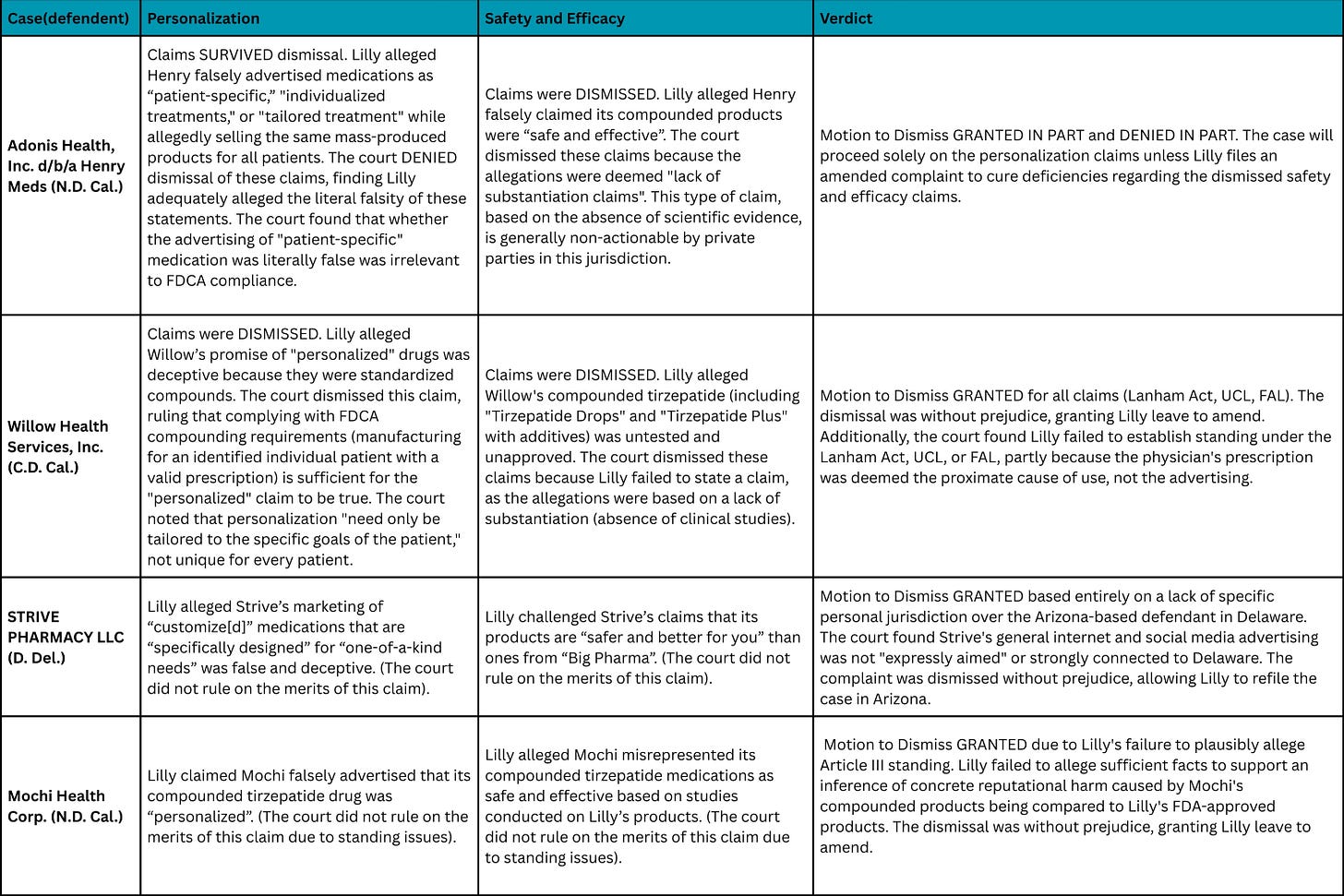

In the Northern District of California, Lilly’s personalization claims against Henry Meds survived dismissal because the court found that Henry advertised “personalised treatment” while everyone received identical pre-made doses regardless of individual circumstances.

But just 400 miles south, the Central District of California dismissed identical personalization claims against Willow, ruling that any prescription drug made for an identified patient with a valid prescription automatically qualifies as “personalized” under FDA compounding requirements.

If courts can’t agree on what “personalized” means, which is the most basic claim in compounding advertising, enforcement becomes nearly impossible at scale. The split will potentially create a patchwork of mini-jurisdictions, each with its own standards. Companies can forum shop, incorporating in friendly districts and adjusting marketing language based on local precedent.

These mixed rulings become fundamentally positive for compounding and frustrating for pharma who will be unable to mount a coordinated attack.

What surprised me even more was how both California courts handled safety and efficacy claims. Both dismissed them outright. Lilly argued that compounders can’t prove their products are safe because they lack FDA approval and clinical trials. The courts ruled these were impermissible “lack of substantiation” claims.

Under California law, plaintiffs must affirmatively prove a product causes harm, not merely that it lacks scientific validation. The burden sits with pharma to demonstrate danger, not with compounders to demonstrate safety.

This ruling has significant implications! Compounded GLP-1 gummies, sublingual drops, and combinations with B12 or other additives remain legally defensible until someone proves actual harm. Marketing these products as safe is permissible absent affirmative evidence of danger, and that’s remarkable when you consider what’s actually being sold.

Novo should be watching these outcomes closely. Lilly is an American company with domestic legal expertise navigating U.S. courts, and they’re still getting inconsistent, unfavourable results. Novo, a Danish “interloper” with arguably less teeth, would likely fare worse. Remember that the compounders don’t need to win these cases; they just need to survive until 2032, when the patents expire, which isn’t that long at all.

As a result, I believe the compounding industry will feel emboldened and continue en masse. Their last big pillar of support will come from consumers themselves because of barriers to coverage from both insurers and employers.

Coverage Is Getting Worse, Not Better

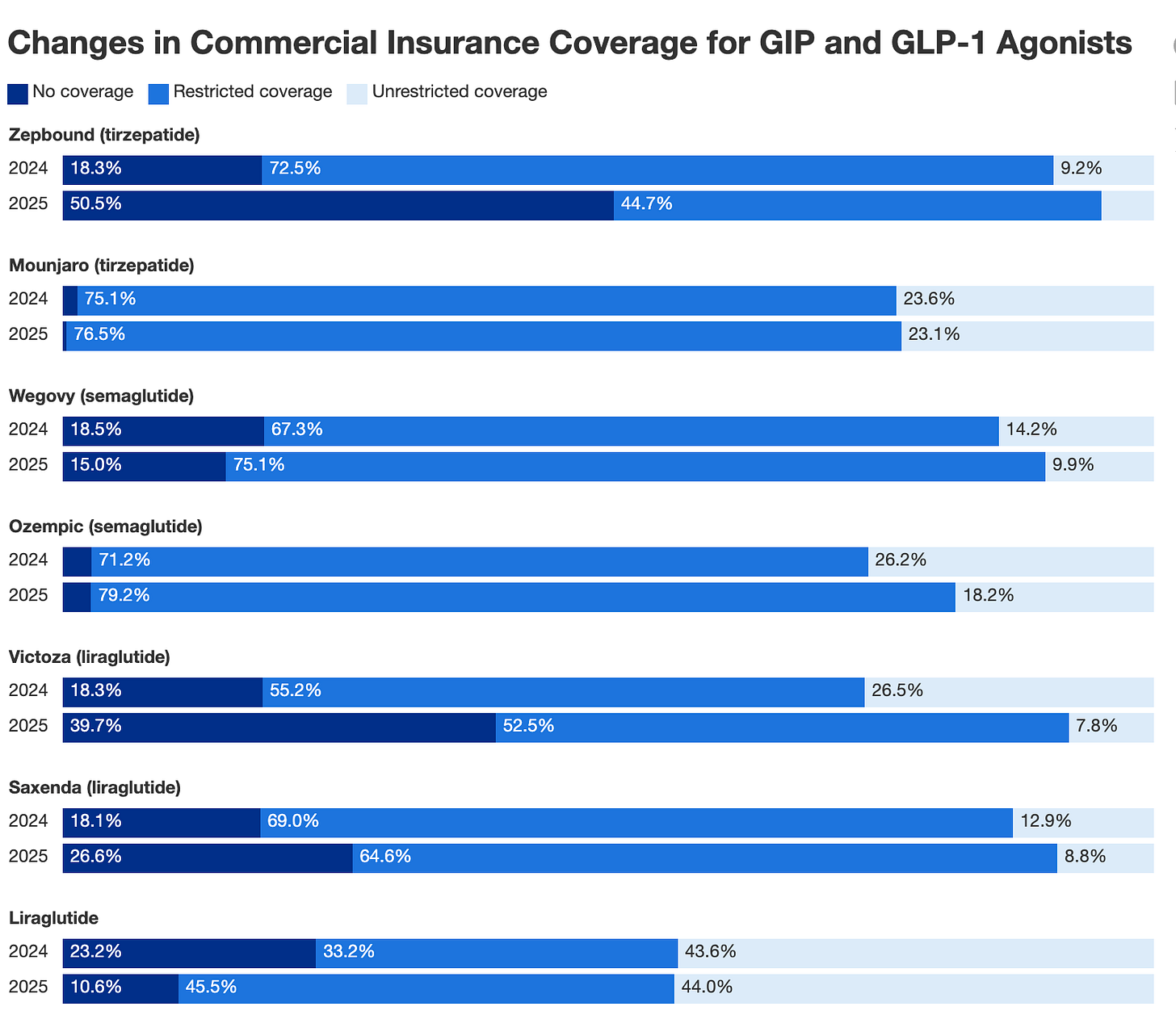

Commercial insurance has not improved in 2025 versus 2024, according to a GoodRx study based on prescription insurance coverage data. The analysis found that the number of people with no commercial insurance for Zepbound increased by 180% in 2025, with an estimated 97 million people without coverage.

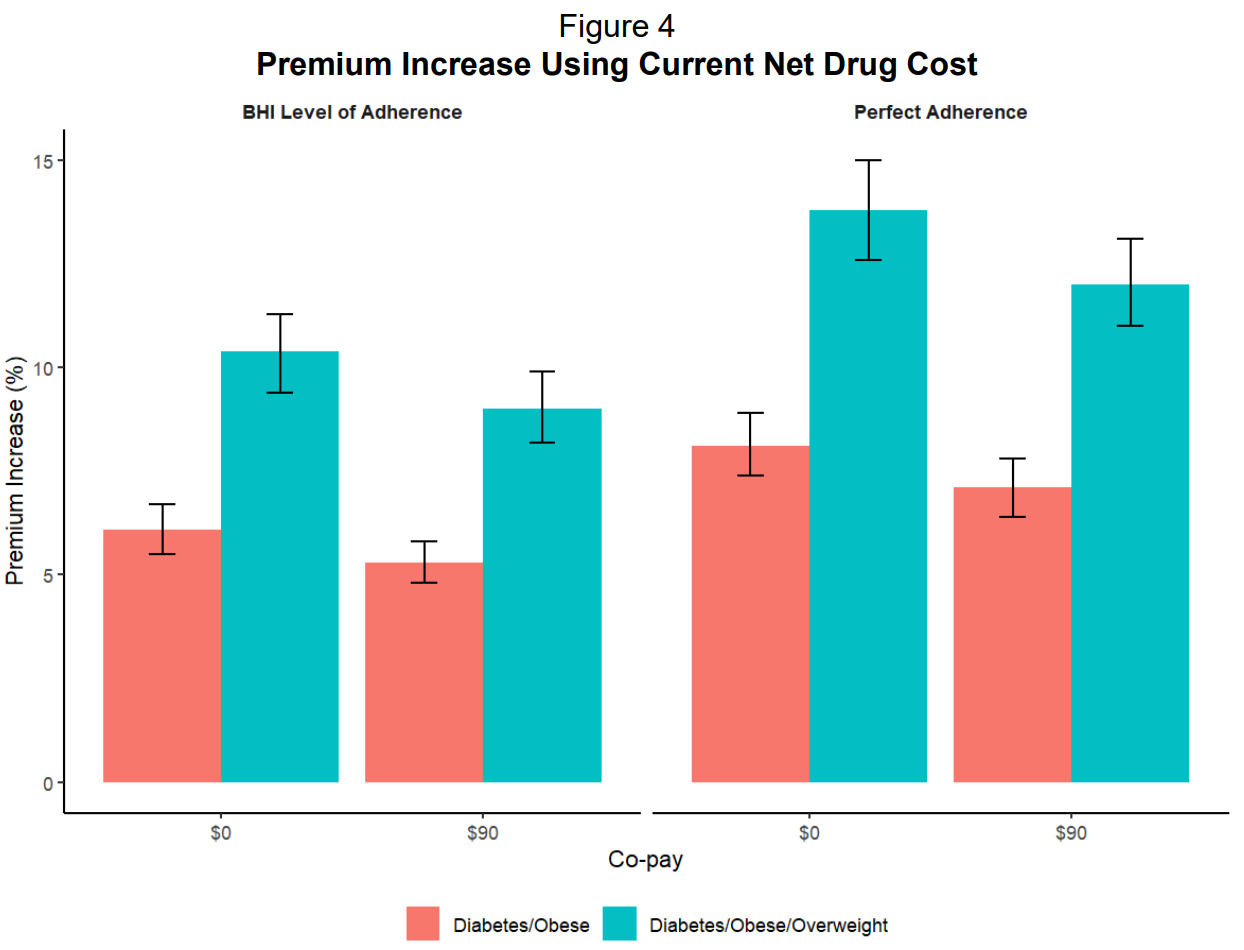

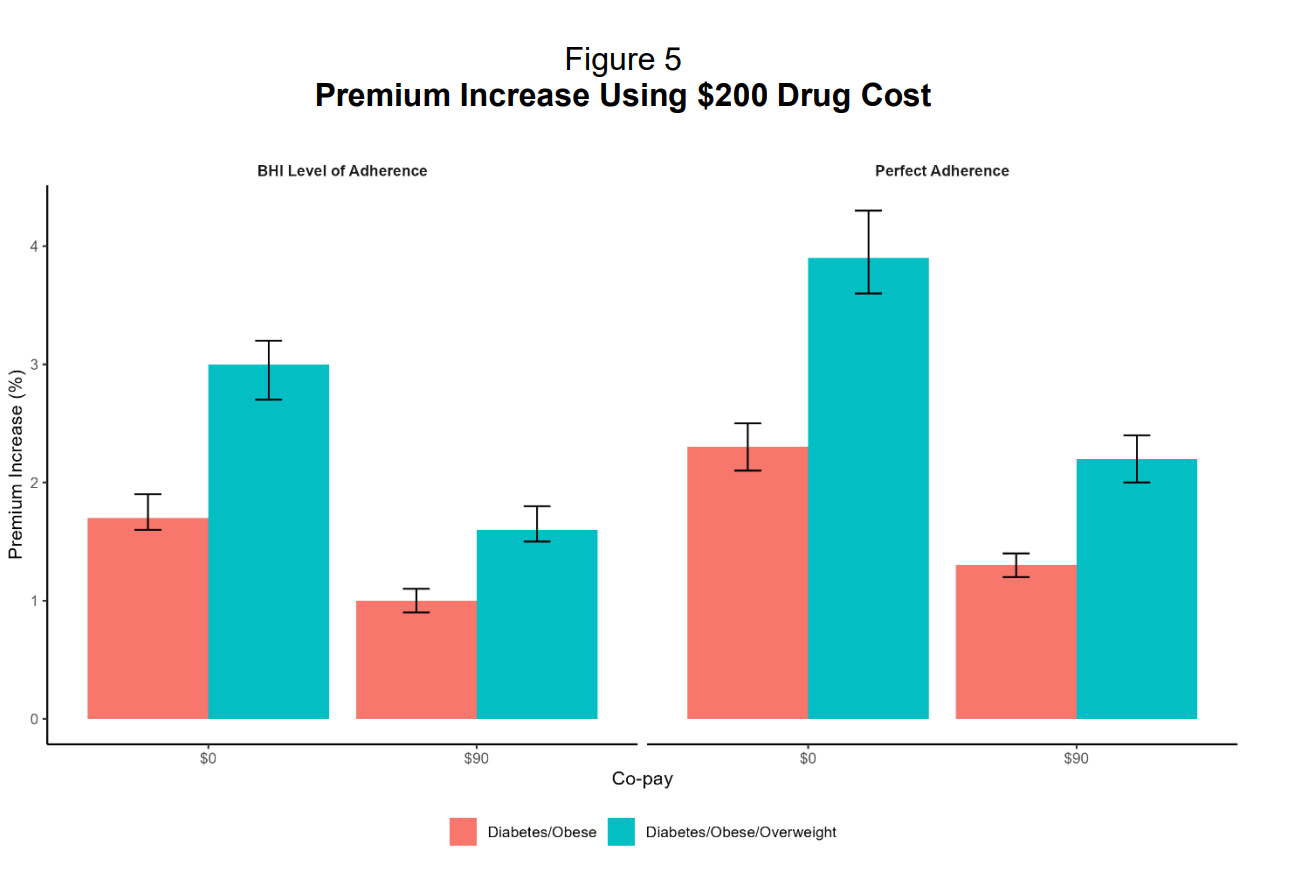

When we look at GLP-1 costs to employers, we can understand why they’re restricting access. A recent EBRI study found that covering GLP-1s increased employer health insurance premiums by 5.3% to 13.8% in year one, assuming current net prices of $617 to $766 per month.

For a typical family plan costing $27,000 annually, that’s an extra $1,400 to $3,700 per year. Since employers cover roughly 70% of premiums, they absorb $1,000 to $2,600 per family in immediate costs while the clinical benefits won’t materialize for 3-5 years.

The EBRI study also found that if everyone actually stayed on the medication (what they call “perfect adherence”), premiums would jump even higher from 6.1% to 8.1% for the same coverage.

This is important because the medications only work if patients take them long term! As I’ve argued many, many times, the weight comes back when people stop. So the high discontinuation rates (26% quit within three months, 36% within a year) don’t actually save employers money either. They just mean patients get neither the health benefits nor the cost savings.

The common argument is that lower drug prices would solve the coverage problem. If GLP-1s became cheaper, insurers would drop their restrictions and more people could access treatment.

The IRA’s Medicare negotiation framework and Medicaid best-price rules will theoretically apply downward pressure on GLP-1 net prices over time, creating spillover effects in commercial contracts because CMS pricing becomes a reference point that commercial payers can leverage in their own negotiations.

The EBRI study tested this theory by modeling GLP-1s at $200 per month instead of $600-$750. Even at that dramatically lower price, premiums still increased between 1% and 3.9%. The problem isn’t the price per dose. It’s that over 40% of privately insured adults qualify for these drugs based on medical guidelines, but only 3% currently take them. If that 3% creeps up to even 10% or 15%, the costs become unmanageable for employers operating on annual budgets.

One benefits manager at a large retailer captured the decision rather bluntly:

The cash price for compounded semaglutide sits around $200 per month, comparable to or cheaper than many employer plan cost-sharing arrangements after deductibles and prior authorization are factored in. Plus, it arrives without paperwork, waiting periods, or claim denials.

It beggars belief that over 88% of people with insurance coverage for GLP-1s for weight loss still face restrictions such as prior authorizations or step therapy, and of course, doctors love this. Their favourite hobby is paperwork!

The issue is that prior authorization and step therapy function as the primary mechanisms for demand control, and when an insurer creates so much friction, they basically say no without explicitly saying no.

As long as insurance access remains clogged by administrative barriers and employers continue pushing members toward cash alternatives, compounding is and will continue to be the solution to a permanent mismatch between clinical demand, pricing, and benefit design capacity.

The conclusion

I don’t think you can put this genie back in the bottle, not when a million patients have discovered they can get the same drug for $200 instead of $1,000 and not deal with all the faff of insurance denying coverage.

I’ve argued before that patent infringement litigation is pharma’s nuclear option, the only legal tool with enough force to actually dent compounding. Will Novo or Lilly press that button? Maybe. Patent litigation is binary, and you either bankrupt the compounders or you lose spectacularly and validate their entire business model. It’s a massive gamble with no middle ground.

So if they don’t go nuclear, what’s left?

Pricing.

They could undercut the compounders by dropping GLP-1 prices to commodity levels. But that means turning their multi-billion dollar franchises into margin-squeezed utilities. After spending a decade and $10 billion on R&D, are they really going to slash prices in year three of commercialization? I don’t think so.

And honestly, I don’t blame them because innovation deserves returns!

But when a market disruptor comes in selling the same ingredient for a fraction of the price, and the FDA accommodates it, and the courts can’t stop it, and insurance economics make branded coverage unsustainable...

Market force will win and guarantee compounding doesn’t go anywhere, anytime soon.

The FDA can just stop the active pharmaceutical ingredient from entering the country and dry up supply by issuing an import alert. Alerts are commonly used for overseas manufacturers who violate FDA standards after a plant inspection. The substance they produce gets flagged at customs and stopped from entering the country. The manufacturer is notified and then has to take steps to be removed from a “red list” and added back to the “green list” for the substance to be imported in the US.

**The views, opinions, and recommendations expressed in this essay are solely my own and do not represent the views, policies, or positions of my employer or any other organization with which I am affiliated. This content is provided for informational purposes only and should not be considered medical, legal or investment advice.**

So for Pharma, what’s the value of R&D at all, when they could be undercut by what is basically a generic wrapped in “compound” coat for any product they develop.

We already have retatrutide in the UK, the public are buying it and using it. Assume we’ll have generic orforglipron and MariTide within the year.

Implications to the whole Pharma model are significant, no?